If Pakistan has not released a nuclear doctrine, it does not mean that it has not got one. It is understandable that a small nuclear power that espouses a limited aim of deterring coercion from a larger neighbour, maintaining calculated ambiguity would be a rational choice. Clear articulation would limit Pakistani options. That said Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine can be ascertained if, for instance, statements by its National Command Authority are read closely.

In September 2013, the NCA signalled that Pakistan would follow Full Spectrum Deterrence which surfaced during NCA meetings in 2015-16. Recently, the 23rd meeting of the NCA has reaffirmed its commitment to FSD.

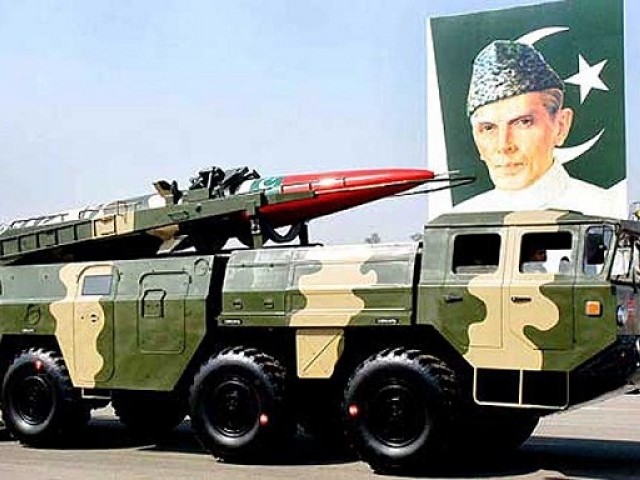

NCA’s adviser for development Lt Gen (retd) Khalid Kidwai has shed rare light on FSD and articulated that by this policy every Indian target is now in Pakistan’s striking range. Elaborating three elements of FSD, he counted the “full spectrum of nuclear weapons, with full range coverage of the large Indian land mass and its outlying territories.” In other words, FSD manifests that the authorities will utilise whatever methods are important to secure its interests.

Analysts see this FSD approach as a qualitative response by Pakistan to counter the threat created by the Indian Cold Start Doctrine. In 2016, the Indian chief of army staff let the cat out of the bag by accrediting CSD — a politically unauthorised doctrine of a limited war under the umbrella of nuclear weapons. The shift in Indian doctrine has left Pakistan with no choice but to go for offensive options.

Pakistan has adopted a method of gradual declaration of its nuclear doctrine, which neither clearly embraces a first use doctrine nor denies it. This bit-by-bit approach is useful because Pakistan responds to Indian actions that remain dynamic. The ambiguity in Pakistan’s posture is meant to deter a pre-emptive conventional attack and establish deterrence rather than practically initiating a nuclear war. This is why Pakistan has developed adequate conventional response mechanism to a pre-emptive conventional war doctrine. Although Pakistan’s nuclear programme is for solely defence purposes, it has always been under consistent threat from a much superior military adversary.

There are numerous examples of threatening to utilise nuclear arsenals in order to compensate for conventional asymmetry. The US, with respect to Nato, adhered to the idea of first use in its long-standing nuclear policy. When the erstwhile USSR broke up, Russia expressly renounced the NFU pledge. The French nuclear doctrine is a hardcore form of first use in which Paris is theoretically working on nuclear weapons usage against conventional threats.

There is an ongoing debate within India to depart from its NFU policy and to adopt a doctrine that comprises the obvious threat of first use, especially to address the asymmetry with China. In such scenario, a declared nuclear stance of a first use option would construct a dilemma for India. Unlike India, Pakistan’s nuclear strategy has always followed a pattern of providing minute information and upheld a calculated ambiguity about its nuclear doctrine.

Henceforth, Pakistani officials will confront two challenges with respect to disclosure of nuclear doctrine. First, how to classify diverse levels of thresholds and to justify the magnitude of these redlines, where a nuclear retaliation could be seen as a possible outcome? Secondly, policymakers have to decide how to balance between clarity and ambiguity of the extent to which a declared policy could go.

If Pakistan wants to establish FSD then along with nuclear capability, it has to expand its conventional capability. In Pakistan’s doctrine of FSD, a foremost exertion should consider improving its conventional capability and operational concepts to deal with evolving threats. Whereas the credible minimum deterrence should remain a foundation element for a flexible nuclear doctrine, ie, FSD. It is important for Pakistan to acquire an assured second-strike capability to counter widening gaps in Indian Ocean strategic stability.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 9th, 2018.

In September 2013, the NCA signalled that Pakistan would follow Full Spectrum Deterrence which surfaced during NCA meetings in 2015-16. Recently, the 23rd meeting of the NCA has reaffirmed its commitment to FSD.

NCA’s adviser for development Lt Gen (retd) Khalid Kidwai has shed rare light on FSD and articulated that by this policy every Indian target is now in Pakistan’s striking range. Elaborating three elements of FSD, he counted the “full spectrum of nuclear weapons, with full range coverage of the large Indian land mass and its outlying territories.” In other words, FSD manifests that the authorities will utilise whatever methods are important to secure its interests.

Analysts see this FSD approach as a qualitative response by Pakistan to counter the threat created by the Indian Cold Start Doctrine. In 2016, the Indian chief of army staff let the cat out of the bag by accrediting CSD — a politically unauthorised doctrine of a limited war under the umbrella of nuclear weapons. The shift in Indian doctrine has left Pakistan with no choice but to go for offensive options.

Pakistan has adopted a method of gradual declaration of its nuclear doctrine, which neither clearly embraces a first use doctrine nor denies it. This bit-by-bit approach is useful because Pakistan responds to Indian actions that remain dynamic. The ambiguity in Pakistan’s posture is meant to deter a pre-emptive conventional attack and establish deterrence rather than practically initiating a nuclear war. This is why Pakistan has developed adequate conventional response mechanism to a pre-emptive conventional war doctrine. Although Pakistan’s nuclear programme is for solely defence purposes, it has always been under consistent threat from a much superior military adversary.

There are numerous examples of threatening to utilise nuclear arsenals in order to compensate for conventional asymmetry. The US, with respect to Nato, adhered to the idea of first use in its long-standing nuclear policy. When the erstwhile USSR broke up, Russia expressly renounced the NFU pledge. The French nuclear doctrine is a hardcore form of first use in which Paris is theoretically working on nuclear weapons usage against conventional threats.

There is an ongoing debate within India to depart from its NFU policy and to adopt a doctrine that comprises the obvious threat of first use, especially to address the asymmetry with China. In such scenario, a declared nuclear stance of a first use option would construct a dilemma for India. Unlike India, Pakistan’s nuclear strategy has always followed a pattern of providing minute information and upheld a calculated ambiguity about its nuclear doctrine.

Henceforth, Pakistani officials will confront two challenges with respect to disclosure of nuclear doctrine. First, how to classify diverse levels of thresholds and to justify the magnitude of these redlines, where a nuclear retaliation could be seen as a possible outcome? Secondly, policymakers have to decide how to balance between clarity and ambiguity of the extent to which a declared policy could go.

If Pakistan wants to establish FSD then along with nuclear capability, it has to expand its conventional capability. In Pakistan’s doctrine of FSD, a foremost exertion should consider improving its conventional capability and operational concepts to deal with evolving threats. Whereas the credible minimum deterrence should remain a foundation element for a flexible nuclear doctrine, ie, FSD. It is important for Pakistan to acquire an assured second-strike capability to counter widening gaps in Indian Ocean strategic stability.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 9th, 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment