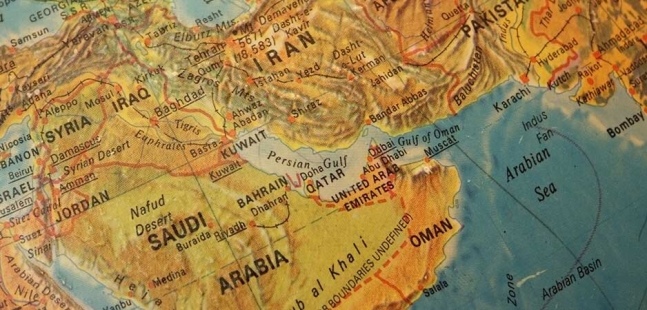

© val lawless / Shutterstock

Trump Might Find Himself Accidentally at War

In this edition of The Interview, Fair Observer talks to the former United Nations weapons inspector in Iraq Scott Ritter.

After Iran shot down a $220-million US unmanned aerial vehicle over the Strait of Hormuz on June 20, President Donald Trump said the United States was “cocked and loaded” to retaliate. He apparently rescinded his decision only 10 minutes before the attack was to be carried out, after his military advisers told him 150 people may die in such a strike.

President Trump is being censured by critics for not having a clear and robust Middle East strategy. He is said to only increase the likelihood of an unwanted, new military confrontation in an already volatile region, resulting from miscalculations that appear to be inevitable when tensions run high. In a recent op-ed, the former German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer wrote that Trump and his team appear to have no idea what policy they should adopt, calling his Iran agenda a “lose-lose strategy.”

The successive US administrations’ Middle East policy in the recent decades has been often described as failed and unsuccessful. Perhaps the most notable example of US failure in the Middle East is the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi citizens and laid the groundwork for the rise of the Islamic State. While it is difficult to calculate the exact human cost of the conflict, the Iraq Body Count project puts the number of civilians killed between 183,774 and 206,403, while other analysis suggests an excess of 500,000 deaths since 2003, and possibly even more.

As a region suffering from corruption, violence and authoritarianism, the Middle East needs solutions, diplomacy, investment and international assistance to be able to overcome its challenges. However, the Trump administration’s noticeable absence of strategy has only made the situation worse.

Scott Ritter, a former Marine Corps intelligence officer, was the United Nations weapons inspector in Iraq from 1991 to 1998, becoming an outspoken critic of the US foreign policy in the Middle East. He argued that Saddam Hussein possessed no significant weapons of mass destruction.

In this edition of The Interview, Fair Observer talks to Ritter about the status quo in the Middle East, President Trump’s foreign policy, US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and the experience of the Iraq War.

The transcript had been lightly edited for clarity.

Kourosh Ziabari: President Donald Trump’s foreign policy is perceptibly based on avoiding military conflicts while being aggressive and assertive. Do you see similarities between Trump’s approach to international affairs and President George W. Bush’s foreign policy agenda?

Scott Ritter: There is an amateurishness that underpins Trump’s foreign policy that makes it difficult to seriously evaluate the extent to which he genuinely seeks to avoid military conflict. One can be assertive and aggressive without actively posturing for conflict. Trump’s blustering creates the conditions for conflict that are only avoided when others back down, such as was the case — initially — with North Korea. Iran is not backing down, and as a result Trump may soon find himself backed into a corner, compelled to fight a war no one wants. The main difference between Trump and Bush 45 is that Bush was serious about projecting US power through military force — Afghanistan and Iraq prove that. If Trump finds himself at war, it will be because of accidental incompetence, as opposed to premeditation.

Ziabari: Upon taking office, President Trump laid out his foreign policy doctrine under three major bullet points, one of which was “embracing diplomacy” aimed at making old enemies into new friends. Do you think Trump has been successful in fulfilling this promise? For example, in the case of Iran, has Trump given diplomacy any chance to work?

Ritter: Diplomacy is premised upon the art of listening, as well as speaking. It is accomplished in an atmosphere of compromise. There is nothing about Trump’s execution of his foreign policy objectives which hints at a willingness to either listen or compromise. If there was, we would still be a member of the JCPOA [Joint Cooperation Plan of Action] and attempting to negotiate our differences without the looming threat of war; we would have an interim denuclearization agreement with North Korea which saw the major facility at Yong Bon dismantled under US supervision while sanctions were eased, and discussions ongoing on how to complete the task; and the US would remain a part of the INF Treaty while negotiating deep and meaningful cuts in strategic nuclear weapons with Russia.

Trump is the antithesis of diplomacy: He does not exercise it, therefore it is irresponsible to assess the probability of Trump-based diplomacy having a chance of succeeding.

Ziabari: President Trump’s view on the Iraq War was that it destabilized the Middle East. The outcome of the war was that it toppled a dictator and, at the same time, caused a massive loss of life. You’ve been engaged with Iraq closely. Was the Iraq War a mistake? Was President Trump talking about the human cost of the war when he said it was a “big fat mistake”?

Ritter: The US decision to invade and subsequently occupy Iraq in 2003 will go down in history as one of the worst foreign policy mistakes since the end of World War II. It paved the way for decades of instability and conflict in the Middle East, Southwest Asia and North Africa. It hastened the decline of the US as a global power. However, giving Trump credit for being “right” on Iraq is misplaced. He cannot articulate the complexity of the issues involved in the decision to go to war with Iraq, or detail the real costs, human or otherwise, brought on by the decision to go to war. He surrounds himself with advisers who believe the US was justified in invading Iraq, and pushes policies which continue or expand on the policy posture of US exceptionalism [and] domination that drove US-Iraqi relations since the 1980s.

Ziabari: Does President Trump’s confrontational approach toward Iran and his uncompromising rhetoric bear similarities to the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq?

Ritter: In so far as Trump’s posture vis-à-vis Iran is predicated on flawed intelligence about Iran’s nuclear ambition, and the US decision to invade Iraq justified by flawed intelligence regarding Iraq’s WMD capability, one could draw such a conclusion. One must keep in mind, however, that President George W. Bush had inherited a policy of regime change in Iraq that dated back to his father’s administration, and was influenced by the policies of both Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton — there was continuity of purpose over three successive administrations.

Bush’s decision to invade was simply the logical conclusion of nearly two decades of flawed policy. Trump, on the other hand, has broken decisively with the policies of President Obama, and in doing so reembraced policy objectives and postures that had been proven to be fundamentally flawed. There is no history backing up Trump’s pronouncements, simply the overheated rhetoric of a dilletante.

Ziabari: In an interview with CNN in 1999, you said you believed the United States seeks stability in the Middle East, which is a noble objective. Do you think this is still the case and that the Trump administration is in favor of stability and peace in the Middle East? Do you think successive administrations after Bill Clinton had a thorough understanding of the realities of the Middle East?

Ritter: One can make the case that the US has always sought stability in the Middle East. The problem is how one defines “stability.” For the Clinton administration, stability hinged on an Israeli-Palestinian peace process and containing the ambitions of Iraq and Iran, while strengthening the hand of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arab nations. George W. Bush based his concept of stability on destroying al-Qaeda and removing Saddam Hussein from power.

Barack Obama recognized the limits of US power and influence, and sought to pull back militarily in Iraq and Afghanistan while reengaging on an Israel-Palestine peace plan. Trump seeks regime change in Iran, and an unrealistic “deal of the century” that resolves in one fell swoop the Arab-Israeli conflict. All plans are predicated on the notion that the US not only knows best but is uniquely empowered to impose its will on the region. All failed or will fail. The sad truth is when the US articulates a desire for peace and stability in the Middle East, the end result is war and regional instability.

Ziabari: The US government invested heavily, both politically and militarily, and also financially, in removing Saddam Hussein from power and rebuilding Iraq. But do you think the investment has paid off, and that Iraq today is the stable democracy the US authorities wanted it to be?

Ritter: The US decision to remove Saddam Hussein from power has resulted in the furtherance of regional instability, the empowerment of Iran, the moral and fiscal bankruptcy of the US, the degradation of US military power and the rise of anti-American Islamic fundamentalist terrorism globally. Iraq is a shell of its former self. There is simply no way anyone can realistically and responsibly articulate a case for Iraq being called a US success story. If anything, the case is that Iraq is an Iranian success story.

Ziabari: The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was a major non-proliferation accord, and it was working as testified by the UN’s atomic watchdog, the IAEA. However, President Trump pulled out of the deal, stating that it was a weak agreement. Won’t the collapse of the JCPOA make the world a less safe place?

Ritter: The JCPOA was a stop-gap measure designed to halt a dangerous slide toward war. It was premised on a formula designed to keep Iran above a so-called “one-year breakout window,” that being the time needed for an unconstrained Iran to manufacture enough fissile material to produce a single nuclear weapon. It had, and has, two fatal flaws. The first is that the US never disavowed its intelligence assessments that Iran had a nuclear weapons program. As such, the myth of Iranian nuclear intent continues to be fostered by Israel and US hardliners. Second, the “sunset” clauses of the JCPOA position Iran to be in a position to violate the “one year” breakout red line at the conclusion of the JCPOA, creating the situation where Iran can produce unlimited amounts of enriched uranium in an unconstrained fashion while the US continues to assess that Iran maintains an undeclared nuclear weapons program.

The JCPOA simply pushed the Iranian nuclear issue down the road. All Trump did in withdrawing from the JCPOA was act on this reality. The only way the JCPOA can make the world a safe place is for the international community, including the US and Israel, to change their collective intelligence assessments to reflect the reality that Iran never had, and does not have, a nuclear weapons program. When this is done, then Iran can operate as permitted under Article IV of the NPT [Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons] without fear of military reprisals. Then and only then will the world be a safer place.

Ziabari: What are the most pressing challenges the United States faces in the Middle East today? Do you think the White House is on the right path to addressing them?

Ritter: The most challenging issue is self-policing US behavior in the Middle East. The region is capable of achieving a self-policing equilibrium without US interference. Iran and Saudi Arabia are capable of diplomatic engagement that could produce common objectives that lead to peaceful coexistence; it is the US presence that makes this impossible. Iran has reached the extent of its post-9/11 Iraq invasion regional realignment; this cannot be undone, and must be accepted as reality by the US and the Gulf Arab states.

The biggest problem is Israel. The US must stop coddling the Israeli government when it comes to the issue of Palestinian statehood and empowering Israel to believe that unilateral acts of military aggression against its neighbors is acceptable behavior. The notion that the US can negotiate a “deal of the century” is derived from the hubris of US exceptionalism that drives US policy. The US has a role to play in global affairs. But the day of the US being able to dictate an outcome based upon unilateral input is long past. Unfortunately, the Trump administration is heading down the wrong way on the path it would need to take to rectify the errors of the past and put the US on course to have a meaningful impact of regional peace and security.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

No comments:

Post a Comment