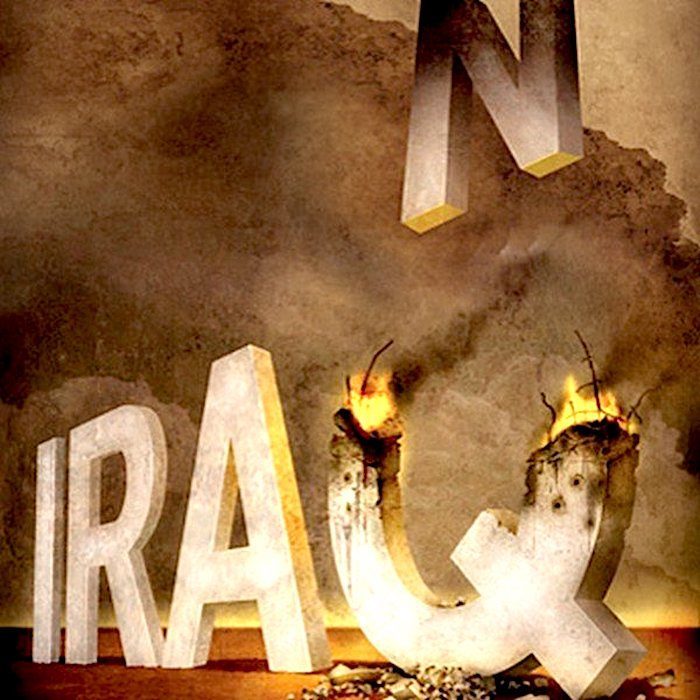

Iraq’s push back on Iran: Will the effects last? | Sabahat Khan | AW

Iraq’s push back on Iran: Will the effects last? | Sabahat Khan | AWRecent months have shown important developments in Iraq’s political landscape, particularly with regards to Iran’s influence in Baghdad.

Some of Iraq’s most important political figures, such as Muqtada al-Sadr, Ammar al-Hakim and Ali al-Sistani, the country’s most senior cleric, have lent support to a fresh narrative and resurgence of Iraqi nationalism that aims for Baghdad to rebalance its regional and international ties.

At the heart of these moves have been interlinked efforts to end corruption, dismantle non-state paramilitary groups and keep Baghdad from permanently becoming a satellite state for Iran or any other country.

Al-Sadr’s narrative has proved both highly popular and divisive, as has often been the case with his political career. For many Iraqis, Iranian support over the years has helped the country overcome an array of threats and challenges. For others, Iran’s interest in Iraq vis-a-vis its regional strategy is too costly and a threat in its own right.

While Iraq remains without a government since parliamentary elections in May, a vote recount affirmed al-Sadr’s surprise electoral win. His Sairoon coalition campaigned on an anti-corruption platform and promised to rein in foreign meddling in Iraqi politics, including specifically Iran.

The Nasr coalition led by incumbent Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who heads a fragile caretaker government, was third behind Hadi al-Amiri, leader of the pro-Iran Badr Organisation.

With the constitution requiring a speaker to be elected before a vote on the new government can be put before legislators, Iraq’s political impasse continues to hold.

Abadi’s Nasr and al-Sadr’s Sairoon coalitions said they had the support of 180 legislators, which would give their more than the 165 seats needed to form a majority. However, the pro-Iran bloc vying for government, led by former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki and Amiri claimed legislators had defected from the Abadi-al-Sadr bloc to theirs and this gave them the largest bloc.

The post-election political deadlock and intense competition is not unusual for Iraq — in 2014, Maliki was reluctant to make way for Abadi even after losing the election. As the political deadlock persists, the possibility of violence breaking out on the streets is also not a new risk.

Closely watched for its Shia-Sunni sectarian problems since 2003, Iraq is entering its most intense period of intra-Shia strife. With religious traditionalists and Iraqi nationalists versus Iran-leaning Iraqi religious ideologues and their paramilitaries, an outbreak of violence would become difficult to curtail.

Tensions are high and the national political backdrop is telling. The Iranian Consulate in Basra was torched by Sunni and Shia protesters chanting “Iran out” — part of protests that began in June prompted by anger over electricity shortages and a lack of clean water.

The past few months have seen the powerful Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU) splintering and problems between its major factions escalated with the conflict over which bloc will form government. Some PMU factions have experienced major losses to their infrastructure due to suspicious attacks and fires, stoking speculation that Iran and its allies were involved.

With the stakes rising, Abadi dismissed Falih Alfayyadh, Iraq’s national security adviser, head of the national security apparatus and the man heading the PMU. Since then, prominent figures in Abadi’s coalition have announced support for Alfayyadh, who effectively still controls the PMU, as the new prime minister ahead of Abadi himself. It is a reminder that Iran’s influence runs deep across Iraq’s political landscape.

Another reminder came when 11 Shia factions in the PMU criticised Abadi’s alliance with al-Sadr’s coalition, which was announced in Najaf in June after they agreed to “supporting the army, placing all arms and weapons under the control of the state, developing a programme to reform the judiciary, activating the role of the general prosecutor to continue combating corruption and holding accountable those accused of corruption.”

Crucially, Abadi and al-Sadr stressed the need to ensure foreign players commit “to not interfere in Iraqi domestic affairs.”

Iran’s influence in Iraq has its limits and those limits are being openly tested like never before. Yet the Iraqi state remains inherently weak, struggling to provide basic services and rein in corruption, deliver a depoliticised bureaucracy and, perhaps most important, contend with regional actors whose geopolitics continue to regard Iraq as a legitimate battleground for regional manoeuvring.

Coalition politics and deal-making continue to be crucial for any national leadership to govern Iraq, with dozens of political groups, armed militias and paramilitary organisations scattered around the country. Many of those elements remain ideologically aligned with Iran.

Thus, any pushback on Iran from Iraq can come only from government rather than from Iraq’s state institutions.

Iran’s influence is undoubtedly entrenched; it can be managed but not uprooted. However Iraqi national politics is experiencing the emergence of forces that can exploit national sentiments and grievances together with regional geopolitics that should secure Baghdad the independence so many Iraqis today desire, as evidenced by this year’s electoral result.

No comments:

Post a Comment