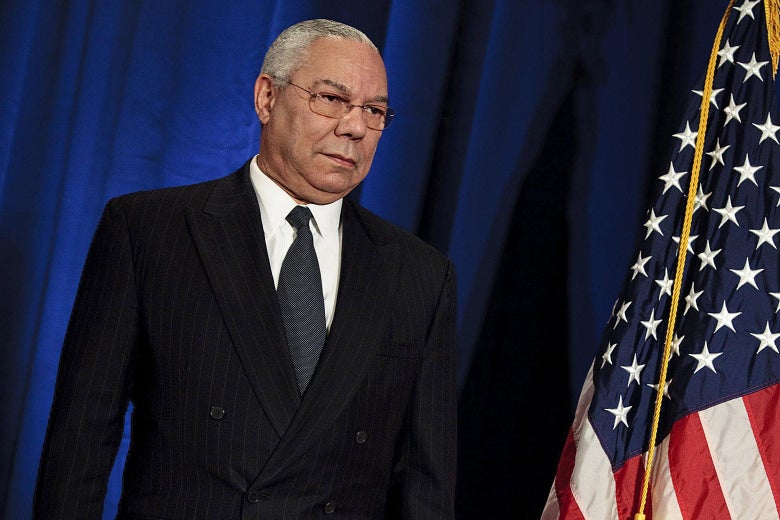

The Moment When Colin Powell Squandered His Spectacular Career

The revered general and statesman, who died Monday, couldn’t outmaneuver his bureaucratic rivals.

Fred KaplanOct 18, 20212:23 PM

Colin Powell, who was the nation’s top diplomat, its top general, and the first Black man to be either, died on Monday at the age of 84. Rarely, if ever, has an American statesman or warrior risen to such heights of power, then been cut off at the knees by his bureaucratic rivals.

Born in Harlem to Jamaican parents, a classic tale of a working-class kid pulling himself up by his own bootstraps, Powell joined the Army, fought in Vietnam as a grunt, rose through the ranks to corps commander, then, after a stint as President Ronald Reagan’s national security adviser, was named by President George H.W. Bush to be chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

As a rare officer who combined battlefield experience with political savvy, Powell turned the chairmanship into a powerhouse, utilizing his large staff—several hundred of the military’s smartest officers, split into several specialized units—in a way that, as one official at the time told me, “ran circles around the rest of the national-security bureaucracy.” It was in that position that Powell emerged as a public figure, devising much of the strategy for the first Gulf War, which pushed Iraq’s invading army out of Kuwait, and explaining the strategy at several televised press conferences.

During that time, he also enunciated what came to be called the “Powell doctrine,” a view that the U.S. should go to war only if the political objectives are vital and defined, if military force can achieve those objectives at an acceptable cost, if all nonviolent means have failed—and then, if war is necessary, that we should go to war only with overwhelming force. The doctrine amounted to a critique of the U.S. intervention in Vietnam—both its flawed rationale and its piecemeal tactics—and has influenced the debate on the proper role of military force ever since.

After Democrats regained the White House in 1992, Powell wrote a bestselling memoir, My American Journey, and considered running for president. (His wife, Alma, urged him not to run, fearing that some racist would assassinate him.) When the Republicans won again in 2000, President George W. Bush named Powell secretary of state, to unanimous acclaim, in what seemed the pinnacle of his rise—but it proved to be the start of his downfall. Taking office with an air of confidence, assuming that he could rule the realm of foreign policy through his clout and popularity, he soon found himself—to his initial surprise—outmaneuvered, on one major issue after another, by the tag team of Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who had been friends and colleagues dating back to the Nixon administration.

Powell accomplished a great deal on issues that Cheney and Rumsfeld didn’t care about. In the fall of 2001, they let him conduct the shuttle diplomacy that may well have prevented war between the nuclear-armed nations of India and Pakistan. Powell also helped soothe tensions with China after its shoot-down of a U.S. spy plane. However, he lost almost every other battle. In one of his first statements, Powell declared that he would resume President Bill Clinton’s nuclear negotiations with North Korea—only to be told by Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security adviser, that he would do no such thing. He had to eat his words.

Whenever Powell tried to initiate any form of arms control, his undersecretary of state, John Bolton, who had been installed in the job as a spy for Cheney, did his best to sabotage the move. On the few occasions when Powell won a debate in the National Security Council, Cheney would go talk with Bush privately—and usually get the decision reversed.

By the middle of Bush’s first term, his counterparts in Europe—who had celebrated Powell’s appointment and spoke with him frequently—came to realize that his views, which they found agreeable, did not reflect the president’s views, and he lost his influence abroad. When Bush wanted to send a message on the Middle East, he sent Rice. When he dispatched an emissary to Western Europe to lobby for Iraqi debt cancellation, he sent James Baker, the Bush family’s longtime friend who had been his father’s secretary of state.

The war in Iraq might have served as Powell’s off-ramp to redemption but instead deepened his downslide to Nowheresville. As Bush crept toward the invasion, Powell warned him of its pitfalls—most prophetically on what he called “the Pottery Barn rule: you break it, you own it”—but to no avail. (Shortly before the war started, a European diplomat reminded him that Bush was said to sleep like a baby. Powell replied, “I sleep like a baby, too—every two hours, I wake up screaming.”) Once again, though, he was outmaneuvered. Unable to muster support for the invasion, either on the homefront or among allies, Cheney came up with the diabolical idea of having Powell—the one senior Bush official with international credibility—make the case for war before the U.N. Security Council. Initially, Powell resisted, tearing up the script the White House gave him to read. But then, in an effort to be helpful and loyal, he went to CIA headquarters and buried himself in documents and briefings for days on end, tossing out claims that had no support and leaving in those that seemed at least plausible. In the end, he gave his fateful speech, with passion. Many critics of the invasion were won over, in good part because it was Colin Powell making the case.

But all the claims that Powell was believed—all the evidence he recited to support the idea that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction—turned out to be false as well. In his excellent book, To Start a War, Robert Draper wrote that plenty of CIA analysts could have told Powell that the claims were false, or at least dubious—but that CIA Director George Tenet, eager to please Bush with the conclusions Bush wanted to hear, deliberately kept Powell from talking with them.

Powell left the administration after Bush’s first term. Toward the end, he was portrayed in several journalistic accounts, most notably Bob Woodward’s Plan of Attack, as a critic of the war who regarded Cheney as having “the fever” for invasion; but, even a year after leaving his post, Powell stayed mum on these matters in public. As late as June 2005, six months into Bush’s second term, Powell went on The Daily Show With Jon Stewart in one of his first TV guest spots since leaving office. Stewart asked questions that left him wide openings to take jabs at his former colleagues, who were still in power, or at the war, which was still raging. But he took none of them. Sure, there were disagreements, Powell said, but that’s true in any administration. The president is the boss, and he’s a swell guy. Why, he and Laura were just over at his house for dinner the previous week.

Powell later openly regretted his role in the U.N. speech and denounced those who’d manipulated him at Langley. Too late. If he had resigned in protest before the invasion, he might have stopped the war from happening; if he had spoken out after leaving office, he might have affected its future course. But this wasn’t his way. He was, at heart, a team player, a “good soldier.”

Over time, he turned away from the Republican Party. In the 2008 presidential election, he endorsed Barack Obama, calling him a “transformational” candidate, to the great dismay of his old friend and Obama’s opponent, Sen. John McCain. However, Obama rarely called him for advice on defense issues. Powell subsequently endorsed only Democrats—Obama again in 2012, Hillary Clinton in 2016, and Joe Biden in 2020.

In recent years, apart from the endorsements, Powell remained out of the limelight of national politics—though it wasn’t clear whether this was by choice. He devoted most of his time to personal and public causes, especially the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at his alma mater, the City College of New York. He wrote more bestselling books and spoke widely, sometimes for fees, sometimes not. He had a wonderful life. At one pivotal moment in our history, it could have been a more decisive one.

No comments:

Post a Comment