Nuclear Notebook: How many nuclear weapons does Pakistan have in 2021?

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, September 7, 2021

Pakistan continues to expand its nuclear arsenal with more warheads, more delivery systems, and a growing fissile materials production industry. Analysis of a large number of commercial satellite images of Pakistani army garrisons and air force bases shows what appear to be launchers and facilities that might be related to the nuclear forces.

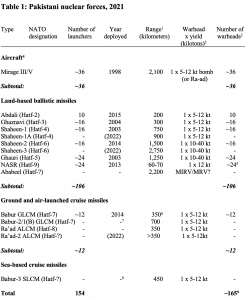

We estimate that Pakistan now has a nuclear weapons stockpile of approximately 165 warheads (See Table 1). The US Defense Intelligence Agency projected in 1999 that Pakistan would have 60 to 80 warheads by 2020 (US Defense Intelligence Agency 1999, 38), but several new weapon systems have been fielded and developed since then, which leads us to the higher estimate.

With several new delivery systems in development, four plutonium production reactors, and an expanding uranium enrichment infrastructure, however, Pakistan’s stockpile has the potential to increase further over the next 10 years. The size of this projected increase will depend on several factors, including how many nuclear-capable launchers Pakistan plans to deploy, how its nuclear strategy evolves, and how much the Indian nuclear arsenal grows. Speculation that Pakistan may become the world’s third-largest nuclear weapon state––with a stockpile of some 350 warheads a decade from now––are, we believe, exaggerated, not least because that would require a buildup two to three times faster than the growth rate over the past two decades. We estimate that the country’s stockpile could more realistically grow to around 200 warheads by 2025, if the current trend continues. But unless India significantly expands its arsenal or further builds up its conventional forces, it seems reasonable to expect that Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal will not continue to grow indefinitely but might begin to level off as its current weapons programs are completed.

Analyzing Pakistan’s nuclear forces is fraught with uncertainty, given that the Pakistani government has never publicly disclosed the size of its arsenal and media sources frequently embellish news stories about nuclear weapons. Therefore, the estimates made in the Nuclear Notebook are based on analysis of Pakistan’s nuclear posture, observations via commercial satellite imagery, previous statements by Western officials, and private conversations with officials.

Pakistan’s nuclear posture

Pakistan is pursuing what it calls a “full spectrum deterrence posture ,” which includes long-range missiles and aircraft for strategic missions, as well as several short-range, lower-yield nuclear-capable weapon systems in order to counter military threats below the strategic level. According to former Pakistani officials, this posture––and its particular emphasis on non-strategic nuclear weapons––is specifically intended as a reaction to India’s perceived “Cold Start” doctrine (Kidwai 2020). This alleged doctrine revolves around India maintaining the capability to launch large-scale conventional strikes or incursions against Pakistani territory below the threshold at which Pakistan would retaliate with nuclear weapons.[i]

In 2015, a former member of Pakistan’s National Command Authority, Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Khalid Kidwai, said the NASR short-range weapon specifically “was born out of a compulsion of this thing that I mentioned about some people on the other side toying with the idea of finding space for conventional war, despite Pakistan nuclear weapons.” Pakistan’s understanding of India’s “Cold Start” strategy was, he said, that Delhi envisioned launching quick strikes into Pakistan within two to four days with eight to nine brigades simultaneously (Kidwai 2015). Such an attack force might involve roughly 32,000–36,000 troops. “I strongly believe that by introducing the variety of tactical nuclear weapons in Pakistan’s inventory, and in the strategic stability debate, we have blocked the avenues for serious military operations by the other side,” Kidwai explained (Kidwai 2015).

After Kidwai’s statement, Pakistan’s Foreign Secretary Aizaz Chaudhry publicly acknowledged the existence of Pakistan’s “low-yield, tactical nuclear weapons,” apparently the first time a top government official had done so (India Today 2015). At the time, the tactical missiles had not yet been deployed but their purpose was further explained by Pakistani defense minister Khawaja M. Asif in an interview with Geo News in September 2016: “We are always pressurised [sic] time and again that our tactical (nuclear) weapons, in which we have a superiority, that we have more tactical weapons than we need. It is internationally recognized that we have a superiority and if there is a threat to our security or if anyone steps on our soil and if someone’s designs are a threat to our security, we will not hesitate to use those weapons for our defense” (Scroll 2016). In developing its nonstrategic nuclear strategy, one study has asserted that Pakistan to some extent has emulated NATO’s flexible response strategy without necessarily understanding how it would work (Tasleem and Dalton 2019).

Pakistan’s nuclear posture—and particularly its pursuit of tactical nuclear weapons—has created considerable concern in other countries, including the United States, which fears that it increases the risk of escalation and lowers the threshold for nuclear use in a military conflict with India. Over the past decade and a half, the US assessment of nuclear weapons security in Pakistan appears to have changed considerably from confidence to concern, particularly as a result of the introduction of tactical nuclear weapons. In 2007, a US State Department official told Congress that, “we’re, I think, fairly confident that they have the proper structures and safeguards in place to maintain the integrity of their nuclear forces and not to allow any compromise” (Boucher 2007). After the emergence of tactical nuclear weapons, the Obama administration changed the tune: “Battlefield nuclear weapons, by their very nature, pose [a] security threat because you’re taking battlefield nuclear weapons to the field where, as you know, as a necessity, they cannot be made as secure,” as US Undersecretary of State Rose Gottemoeller told Congress in 2016 (Economic Times 2016).

The Trump administration echoed this assessment in 2018: “We are particularly concerned by the development of tactical nuclear weapons that are designed for use in battlefield. We believe that these systems are more susceptible to terrorist theft and increase the likelihood of nuclear exchange in the region” (Economic Times 2017a). The Trump administration’s South Asia strategy in 2017 urged Pakistan to stop sheltering terrorist organizations, and noted the need to “prevent nuclear weapons and materials from coming into the hands of terrorists” (The White House 2017).

The Biden administration appears to share the concern but with a broader aperture. In the 2019 Worldwide Threat Assessment, US Director of National Intelligence Daniel R. Coats said, “Pakistan continues to develop new types of nuclear weapons, including short-range tactical weapons, sea-based cruise missiles, air-launched cruise missiles, and longer-range ballistic missiles,” noting that “the new types of nuclear weapons will introduce new risks for escalation dynamics and security in the region” (Coats 2019, 10).

Pakistani officials, for their part, reject such concerns. In 2021, Prime Minister Imran Khan stated that he was “not sure whether we’re growing [the nuclear arsenal] or not because as far as I know…the only one purpose [of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons]––it’s not an offensive thing.” He added that “Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is simply as a deterrent, to protect ourselves” (Laskar 2021). Pakistani officials have also challenged the notion that the security of their nuclear weapons is deficient. Samar Mubarik Mund, the former director of the country’s National Defense Complex, explained in 2013 that a Pakistani nuclear warhead is “assembled only at the eleventh hour if [it] needs to be launched. It is stored in three to four different parts at three to four different locations. If a nuclear weapon doesn’t need to be launched, then it is never available in assembled form” (World Bulletin 2013). Additionally, in 2017 the National Command Authority reviewed the “Nuclear Security Regime” of the nuclear arsenal and expressed “full confidence” in both Pakistan’s command and control systems and existing security measures meant to “ensure comprehensive stewardship and security of strategic assets and materials.” It lauded the nuclear arsenal’s “high standards of training and operational readiness” (ISPR 2017d). These statements on security and safety were, in part, a response to international concern that Pakistan’s evolving arsenal––particularly its growing inventory of short-range nuclear weapon systems––could lead to problems with warhead management and command and control during a crisis. Satellite images show that security perimeters around many bases and military facilities have been upgraded over the past decade in response to terrorist attacks.

Nuclear policy and operational decision-making in Pakistan are undertaken by the National Command Authority, which is chaired by the prime minister and includes both high-ranking military and civilian officials. The primary nuclear-related body within the National Command Authority is the Strategic Plans Division (SPD), which has been described by the former Director of the SPD’s Arms Control and Disarmament Affairs as “a unique organization that is incomparable to any other nuclear-armed state. From operational planning, weapon development, storage, budgets, arms control, diplomacy, and policies related to civilian applications for energy, agriculture, and medicine, etc., all are directed and controlled by SPD.” Additionally, SPD “is responsible for nuclear policy, strategy and doctrines. It formulates force development strategy for the tri-services strategic forces, operational planning at the joint services level, and controls movements and deployments of all nuclear forces. SPD implements NCA’s employment decisions for nuclear use through its NC3 systems” (Khan 2019).

The National Command Authority was convened after India and Pakistan engaged in open hostilities in February 2019, when Indian fighters dropped bombs near the Pakistani town of Balakot in response to a suicide bombing conducted by a Pakistan-based militant group. In retaliation, Pakistani aircraft shot down and captured an Indian pilot before returning him a week later and convened the National Command Authority. Following the meeting, a senior Pakistani official gave what appeared to be a thinly veiled nuclear threat: “I hope you know what the [National Command Authority] means and what it constitutes. I said that we will surprise you. Wait for that surprise. … You have chosen a path of war without knowing the consequence for the peace and security of the region” (Abbasi 2019).

The nuclear weapons production complex

Pakistan has a well-established and diverse fissile material production complex that is expanding. It includes the Kahuta uranium enrichment plant east of Islamabad, which appears to be growing with the near completion of what could be another enrichment plant, as well as the enrichment plant at Gadwal to the north of Islamabad (Albright, Burkhard, and Pabian 2018). Four heavy-water plutonium production reactors appear to have been completed at what is normally referred to as the Khushab Complex some 33 kilometers (20 miles) south of Khushab in Punjab province. Three of the reactors at the complex have been added in the past 10 years. The addition of a publicly confirmed thermal power plant at Khushab provides new information for estimating the power of the four reactors (Albright et al. 2018a). The New Labs Reprocessing Plant at Nilore, east of Islamabad, which reprocesses spent fuel and extracts plutonium, has been expanded. Meanwhile, a second reprocessing plant located at Chashma in the northwestern part of Punjab province may have been completed and become operational by 2015 (Albright and Kelleher-Vergantini 2015). A significant expansion to the Chashma complex was under construction between 2018 and 2020, although it remains unclear whether the reprocessing plant continued to operate throughout that period (Hyatt and Burkhard 2020).

Nuclear-capable missiles and their mobile launchers are developed and produced at the National Defence Complex (sometimes called the National Development Complex) located in the Kala Chitta Dahr mountain range west of Islamabad. The complex is divided into two sections. The western section south of Attock appears to be involved in development, production, and test-launching of missiles and rocket engines. The eastern section north of Fateh Jang is involved in production and assembly of road-mobile transporter erector launchers (TELs), which are designed to transport and fire missiles. Satellite images show the presence of launchers for Shaheen I and Shaheen II ballistic missiles and Babur cruise missiles. The Fateh Jang section has been expanded significantly with several new launcher assembly buildings over the past 10 years, and the complex continues to expand. Other launcher and missile-related production and maintenance facilities may be located near Tarnawa and Taxila.RELATED: Nuclear Notebook: How many nuclear weapons does North Korea have in 2021?

Little is publicly known about warhead production, but experts have suspected for many years that the Pakistan Ordnance Factories near Wah, northwest of Islamabad, serve a role. One of the Wah factories is located near a unique facility with six earth-covered bunkers (igloos) inside a multi-layered safety perimeter with armed guards. The security perimeter was expanded significantly between 2005 and 2010, possibly in response to terrorist attacks against other military facilities.

A frequent oversimplification for estimating the number of Pakistani nuclear weapons is to derive the estimate directly from the amount of weapon-grade fissile material produced. As of the beginning of 2020, the International Panel on Fissile Materials estimated that Pakistan had an inventory of approximately 3,900 kilograms (kg) of weapon-grade (90 percent enriched) highly enriched uranium (HEU), and about 410 kg of weapon-grade plutonium (International Panel on Fissile Materials 2021). This material is theoretically enough to produce between 285 and 342 warheads, assuming that each first-generation implosion-type warhead’s solid core uses either 15 to 18 kg of weapon-grade HEU or 5 to 6 kg of plutonium.

However, calculating stockpile size based solely on fissile material inventory is an incomplete methodology that tends to produce inflated numbers. Instead, warhead estimates must take several factors into account: the amount of weapon-grade fissile material produced, warhead design choice and proficiency, warhead production rates, numbers of operational nuclear-capable launchers, how many of those launchers are dual-capable, nuclear strategy, and statements by government officials.

Estimates must assume that not all of Pakistan’s fissile material has ended up in warheads. Like other nuclear weapon states, Pakistan probably maintains a reserve. Moreover, Pakistan simply lacks enough nuclear-capable launchers to accommodate 285 to 342 warheads; furthermore, all of Pakistan’s launchers are thought to be dual-capable, which means that some of them, especially the shorter-range systems, presumably are assigned non-nuclear missions as well—perhaps even primarily. Finally, official statements often refer to “warheads” and “weapons” interchangeably, without making it clear whether it is the number of launchers or the warheads assigned to them that are being discussed.

The amount of fissile material in warheads—and the size of the warhead—can be reduced, and their yield increased, by using tritium to “boost” the fission process. But Pakistan’s tritium production capability is poorly understood. A German company allegedly provided Pakistan with a small amount of tritium and some tritium-processing technology in the late 1980s (Kalinowski and Colschen 1995; Gordon 1989), and China allegedly shipped some tritium directly to Pakistan (Kalinowski and Colschen 1995, 147, 181). The Khushab complex for years has been rumored to produce tritium, and the PINSTECH complex near Nilore may do so as well (FAS 2000a).[ii] However, one rumored tritium extraction plant at Khushab turned out to be a coal-fired power plant (Burkhard, Lach, and Pabian 2017). Pakistan claimed that all its nuclear tests in 1998 were tritium-boosted HEU designs, but the yields detected by seismic signals were not sufficient to substantiate such a capability. Nonetheless, Thomas Reed and Danny Stillman conclude in The Nuclear Express that the tests included two designs, the first of which was an HEU device that used boosting. The second test involved a plutonium device (Reed and Stillman 2009, 257–258).

One study in early 2021 estimated that Pakistan could have produced 690 grams of tritium by the end of 2020, sufficient to boost over 100 weapons. The study assessed that warheads produced for delivery by the Babur and Ra-ad cruise missiles and the NASR and Abdali missiles almost certainly would require a small, lightweight tritium-boosted fission weapon (Jones 2021). If Pakistan has produced tritium and uses it in second-generation single-stage boosted warhead designs, then the estimated 3,900 kg HEU and 410 kg weapon-grade plutonium would potentially allow it to build between 407 and 428 warheads, assuming that each weapon used either 12 kg of HEU or 4 to 5 kg of plutonium.

Despite these uncertainties, Pakistan is clearly engaged in a significant build-up of its nuclear forces and has been for some time. In 2008, Peter Lavoy, then a US intelligence officer for South Asia, told NATO that Pakistan was producing nuclear weapons at a faster rate than any other country in the world (US NATO Mission 2008). Six years later, in 2014, Lavoy described the purpose of the “expansion of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program to include efforts to significantly increase fissile material production to design and fabricate multiple nuclear warheads with varying sizes and yields, [and] to develop, test and ultimately deploy a wide variety of delivery systems with a wide range to include battlefield range ballistic delivery systems for tactical nuclear weapons” (Emphasis added) (Gul 2014).[iii]

Kidwai acknowledged in March 2015 that Pakistan “possesses a variety of nuclear weapons, in different categories. At the strategic level, at the operational level, and the tactical level” (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2015, 6). In December 2017 he provided more details, saying Pakistan’s nuclear strategy required the “full spectrum of nuclear weapons in all three categories—strategic, operational, and tactical, with full range coverage of the large Indian land mass and its outlying territories.” He further explained that the stockpile should have “appropriate weapons yield coverage and the numbers to deter the adversary’s pronounced policy of massive retaliation.” The weapons would give the Pakistani leadership the “liberty of choosing from a full spectrum of targets, notwithstanding the [Indian] Ballistic Missile Defence, to include counter-value, counter-force, and battlefield” targets. He added this implied that “counter-massive retaliation punishment will be as severe if not more” (Dawn 2017).

How far Pakistan plans to go in terms of developing a full-spectrum deterrent posture is unclear. It has provided no public statements about its intent. In 2015, however, Kadwai said that “the program is not open ended. It started with a concept of credible minimum deterrence, and certain numbers [of weapons] were identified, and those numbers, of course, were achieved not too far away in time. Then we translated it, like I said, to the concept of full spectrum deterrence” in response to India’s Cold Start doctrine. As a result, he went on, “the numbers were modified. Now those numbers, as of today, and if I can look ahead for at least 10 to 15 more years, I think they are going to be more or less okay.” He further noted, “we’re almost 90, 95 percent there in terms of the goals that we had set out to achieve” 15 years ago (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2015, 6, 12).

We estimate that Pakistan currently is producing sufficient fissile material to build 14 to 27 new warheads per year, although we estimate that the actual warhead increase in the stockpile probably averages around 5-10 warheads per year.[iv]

Nuclear-capable aircraft

The aircraft most likely to have a nuclear delivery role are Pakistan’s Mirage III and Mirage V fighter squadrons. The Pakistani Air Force’s (PAF) Mirage fighter-bombers are focused at two bases. Masroor Air Base outside Karachi houses the 32nd Wing with three Mirage squadrons: 7th Squadron (“Bandits”), 8th Squadron (“Haiders”), and 22nd Squadron (“Ghazis”). A possible nuclear weapons storage site is located five km (three miles) northwest of the base (Kristensen 2009), and since 2004, unique underground facilities have been constructed at Masroor that could potentially be designed to support a nuclear strike mission. This includes a possible alert hangar with underground weapons-handling capability.[v] The other Mirage base is Rafiqui Air base near Shorkot, which is home to the 34th Wing with two Mirage squadrons: the 15th Squadron (“Cobras”) and the 27th Squadron (“Zarras”).

The Mirage V is believed to have been given a strike role with Pakistan’ small arsenal of nuclear gravity bombs, while the Mirage III has been used for test launches of Pakistan’s Ra’ad (Hatf-8) air-launched cruise missile (ALCM), as well as the follow-on Ra’ad-II ALCM. The Pakistani Air Force has added an aerial refueling capability to the Mirage, a capability that would greatly enhance the nuclear strike mission (AFP 2018).

The air-launched, dual-capable Ra’ad ALCM is believed to have been test-launched at least six times, most recently in February 2016. The Pakistani government states that the Ra’ad “can deliver nuclear and conventional warheads with great accuracy” (ISPR 2011c) to a range of 350 km, and “complement[s] Pakistan’s deterrence capability” by achieving “strategic standoff capability on land and at sea” (ISPR 2016a). During a military parade in 2017, Pakistan displayed what was said to be Ra’ad-II ALCM, apparently an enhanced version of the original Ra’ad with a new engine air-intake and tail wing configuration (Khan 2017). The Pakistani government tested the Ra’ad-II in February 2020 and stated that the missile can reportedly reach targets at a distance of 600 km (ISPR 2020a). All test launches involving either Ra’ad system have been conducted from Mirage III aircraft, indicating its likely delivery system upon deployment.

There is no available evidence to suggest that either Ra’ad system had been deployed as of July 2021; however, one potential deployment site could eventually be Masroor Air Base outside Karachi, which is home to several Mirage squadrons and includes unique underground facilities that might be associated with nuclear weapons storage and handling.

The PAF’s Mirage aircraft are aging, and Pakistan intends to acquire 186 JF-17 aircraft––which are co-produced with China––to replace them (Warnes 2020; Quwa 2021; Gady 2020). According to the Pakistani Senate Defense Committee on National Defence, the pursuit of the JF-17 program was partially triggered by US military export sanctions in response to Pakistan’s nuclear program, including the withholding of F-16 aircraft. “With spares for its top-of-the-line F16s in question, and additional F-16s removed as an option, Pakistan sought help from its Chinese ally” for the JC-17/FC-1 jet (Senate Committee on National Defense 2016). Initial reports from 2016 suggested that Pakistan intended to incorporate the dual-capable Ra’ad ALCM onto the JF-17 in order to allow the newer aircraft to eventually take over the nuclear strike role from the Mirage III/Vs; however, more recent reporting has not confirmed this (Ansari 2013; Fisher 2016).

The nuclear capability of the PAF’s F-16 aircraft is uncertain. Pakistan’s F-16A/Bs were supplied by the United States between 1983 and 1987. After 40 aircraft had been delivered, the US State Department told Congress in 1989: “None of the F–16s Pakistan already owns or is about to purchase is configured for nuclear delivery,” and Pakistan “will be obligated by contract not to modify” additional F-16s “without the approval of the United States” (Schaffer 1989). Yet there were multiple credible reports at the time that Pakistan was already modifying US-supplied F-16s for nuclear weapons, including West German intelligence officials reportedly telling Der Spiegel that Pakistan had already developed sophisticated computer and electronic technology to outfit the US F–16s with nuclear weapons” (Associated Press 1989). Delivery of additional F-16s, including the more modern F-16C/D version, was delayed by concern over Pakistan’s emerging nuclear weapons program. The United States withheld delivery in the 1990s. But the policy was changed by the George W. Bush administration, which supplied Pakistan with the more modern F-16s.

The F-16A/Bs are based with the 38th Wing at Mushaf (formerly Sargodha) Air Base, 160 kilometers (100 miles) northwest of Lahore. Organized into the 9th and 11th Squadrons (“Griffins” and “Arrows” respectively), these aircraft have a range of 1,600 km (extendable when equipped with drop tanks) and most likely are equipped to each carry a single nuclear bomb on the centerline pylon. Security perimeters at the base have been upgraded since 2014. If the F-16s have a nuclear strike mission, the nuclear gravity bombs would likely not be stored at the base itself but could potentially be kept at the Sargodha Weapons Storage Complex 10 km to the south. In a crisis, the bombs could quickly be transferred to the base, or the F-16s could disperse to bases near underground storage facilities and receive the weapons there. Pakistan appears to be reinforcing the munitions bunkers and installing extra security perimeters at the Sargodha complex.

The newer F-16C/Ds are based with the 39th Wing at Shahbaz Air Base outside Jacobabad. The wing upgraded to F-16C/Ds from Mirages in 2011 and so far has one squadron: the 5th Squadron (known as the “Falcons”). The base has been under significant expansion, with numerous weapons bunkers added since 2004. If the base has a nuclear mission, we suspect that the weapons are stored elsewhere in special storage facilities. There are also F-16s visible at Minhas (Kamra) Air Base northwest of Islamabad, although that might be related to aircraft industry at the base.RELATED: Watch now—The UK’s new nuclear posture: What it means for the global nuclear order

In light of uncertainties regarding Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft, the PAF’s F-16s and JF-17s are not identified in this Nuclear Notebook as having a dedicated nuclear weapon delivery system and are omitted from Table 1.

Land-based ballistic missiles

Pakistan appears to have six currently operational nuclear-capable land-based ballistic missiles: the short-range Abdali (Hatf-2), Ghaznavi (Hatf-3), Shaheen-I (Hatf-4), and NASR (Hatf-9), and the medium-range Ghauri (Hatf-5) and Shaheen-II (Hatf-6). Three other nuclear-capable ballistic missiles are under development: the medium-range Shaheen-IA, Shaheen-III, and the MIRVed Ababeel. All of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable missiles––with the exception of the Abdali, Ghauri, Shaheen-II, and Ababeel––were showcased at the Pakistan Day Parade in March 2021 (ISPR 2021a).

The Pakistani road-mobile ballistic missile force has undergone significant development and expansion over the past decade-and-a-half. This includes possibly eight or nine missile garrisons, including four or five along the Indian border for short-range systems (Babur, Ghaznavi, Shaheen-I, NASR) and three or four other garrisons further inland for medium-range systems (Shaheen-II and Ghauri).[vi]

The short-range, solid-fuel, single-stage Abdali (Hatf-2) has been in development for a long time. The Pentagon reported in 1997 that the Abdali appeared to have been discontinued, but flight-testing resumed in 2002, and it was last reported test launched in 2013. The 200-km (124-mile) missile has been displayed at parades several times on a four-axle road-mobile transporter erector launcher (TEL). The gap in flight-testing indicates the Abdali program may have encountered technical difficulties. After the 2013 test, Inter Services Public Relations stated that Abdali “carries nuclear as well as conventional warheads” and “provides an operational-level capability to Pakistan’s Strategic Forces.” It said the test launch “consolidates Pakistan’s deterrence capability both at the operational and strategic levels” (ISPR 2013a).

The short-range, solid-fuel, single-stage Ghaznavi (Hatf-3) was test launched in 2019, 2020, and 2021––its first reported test launches since 2014. In an important milestone for testing the readiness of Pakistan’s nuclear forces, the 2019 Ghaznavi launch was conducted at night. After each test, the Pakistani military stated that the Ghaznavi is “capable of delivering multiple types of warheads up to a range of 290 kilometers” (ISPR 2019a; ISPR 2020b; ISPR 2021b). Its short range means that the Ghaznavi cannot strike Delhi from Pakistani territory, and Army units equipped with the missile are probably based relatively near the Indian border (Kristensen 2016).

The Shaheen-I (Hatf-4) is a single-stage, solid-fuel, dual-capable, short-range ballistic missile with a maximum range of 650 km that has been in service since 2003. The Shaheen-I is carried on a four-axle, road-mobile TEL similar to the one used for the Ghaznavi. Since 2012, many Shaheen-I test launches have involved an extended-range version widely referred to as Shaheen-IA. The Pakistani government, which has declared the range of the Shaheen-IA to be 900 km (560 miles), has used both designations. Pakistan most recently test launched the Shaheen-I in November 2019 and the Shaheen-IA in March 2021 (ISPR 2019b; ISPR 2021c). Potential Shaheen-1 deployment locations include Gujranwala, Okara, and Pano Aqil.[vii]

One of the most controversial new nuclear-capable missiles in the Pakistani arsenal is the NASR (Hatf-9), a short-range, solid-fuel missile originally with a range of only 60 km (37 miles) that has recently been extended to 70 km (43 miles) (ISPR 2017a). With a range too short to attack strategic targets inside India, NASR appears intended solely for battlefield use against invading Indian troops.[viii] According to the Pakistani government, the NASR “carries nuclear warheads of appropriate yield with high accuracy, shoot and scoot attributes” and was developed as a “quick response system” to “add deterrence value” to Pakistan’s strategic weapons development program “at shorter ranges” in order “to deter evolving threats,” including evidently India’s so-called Cold Start doctrine (ISPR 2011b, 2017a). More recent tests of the NASR system––including two tests in the same week in January 2019––tested the system’s salvo-launch capability, as well as the missiles’ in-flight maneuverability (ISPR 2019c; ISPR 2019d).

The NASR’s four-axle, road-mobile TEL appears to use a snap-on system that can carry two or more launch-tube boxes, and the system has been tested in the past using a road-mobile quadruple box launcher. The US intelligence community has listed the NASR as a deployed system since 2013 (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2013), and with a total of 15 tests reported so far, the weapon system appears to be well-developed. Potential deployment locations include Gujranwala, Okara, and Pano Aqil.[ix]

The medium-range, two-stage, solid-fuel Shaheen-II (Hatf-6) appears to be operational after many years of development. Pakistan’s National Defense Complex has assembled Shaheen-II launchers since at least 2004 or 2005 (Kristensen 2007), and a 2020 US intelligence community report states that there are “fewer than 50” Shaheen-II launchers deployed (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). After the most recent Shaheen-II test launch in May 2019, the Pakistani government reported the range as only 1,500 km (932 miles), but the US National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) continues to set the Shaheen-II’s range at 2,000 km (ISPR 2019e; National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). The Shaheen-II is carried on a six-axle, road-mobile TEL and can carry a single conventional or nuclear warhead.

Pakistan’s newer Shaheen-III medium-range, two-stage, solid-field Shaheen-III was displayed publicly for the first time at the 2015 Pakistan Day Parade. Following its first two test launches in 2015 and its latest launch in January 2021, the Pakistani government said the missile was capable of delivering either a single nuclear or conventional warhead to a range of 2,750 km (ISPR 2021d). The Shaheen-III is carried on an eight-axle TEL reportedly supplied by China (Panda 2016). The system will likely still require several more test launches before it becomes operational.

The range of the Shaheen-III is sufficient to target all of mainland India from launch positions in most of Pakistan south of Islamabad. But the missile was apparently developed to do more than that. According to Gen. Kidwai, the range of 2,750 km was determined by a need to be able to target the Nicobar and Andaman Islands in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean that are “developed as strategic bases” where “India might think of putting its weapons” (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2015, 10). But for a 2,750-km range Shaheen-III to reach the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, it would need to be launched from positions in the very Eastern parts of Pakistan, close to the Indian border. If deployed in the Western parts of Balochistan province, however, the range of the Shaheen-III would for the first time bring Israel within range of Pakistani nuclear missiles.

Pakistan’s oldest nuclear-capable medium-range ballistic missile, the road-mobile, single-stage, liquid-fuel Ghauri (Hatf-5), was most recently test-launched in October 2018. (ISPR 2018c). The Pakistani government states that the Ghauri can carry a single conventional or nuclear warhead to a range of 1,300 km (807 miles), although NASIC lists the range as 1,250 km (776 miles) (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). NASIC also suggests that “fewer than 50” Ghauri launchers have been deployed (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). The extra time needed to fuel the missile before launch makes the Ghauri more vulnerable to attack than Pakistan’s newer solid-fuel missiles, so it is possible that the longer-range versions of the Shaheen may eventually replace the Ghauri.[x] Potential deployment areas for the Ghauri include the Sargodha Central Ammunition Depot area.[xi]

On January 24, 2017, Pakistan test launched a new medium-range ballistic missile––Ababeel––that the government says is “capable of carrying multiple warheads, using multiple independent reentry vehicle (MIRV) technology” (ISPR 2017b).[xii] The three-stage, solid-fuel, nuclear-capable missile, which is currently under development at the National Defense Complex, appears to be derived from the Shaheen-III airframe and solid-fuel motor and has a range of 2,200 km (1,367 miles). (ISPR 2017b; National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). After the test-launch, the Pakistani government declared that the test was intended to validate the missile’s “various design and technical parameters,” and that Ababeel is “aimed at ensuring survivability of Pakistan’s ballistic missiles in the growing regional Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) environment,” “further reinforce[ing] deterrence” (ISPR 2017b). Development of multiple-warhead capability appears to be intended as a countermeasure against India’s planned ballistic missile defense system (Tasleem 2017).

Ground- and sea-launched cruise missiles

Pakistan’s family of ground- and sea-launched cruise missiles is undergoing significant development with work on several types and modifications. The Babur (Hatf-7) is a subsonic, dual-capable cruise missile with a similar appearance to the US Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile, the Chinese DH-10 ground-launched cruise missile, and the Russian air-launched AS-15. The Pakistani government describes the Babur as having “stealth capabilities” and “pinpoint accuracy” and “a low-altitude, terrain-hugging missile with high maneuverability” (ISPR 2011a, 2016b, 2018a). The Babur is much slimmer than Pakistan’s ballistic missiles, suggesting some success with warhead miniaturization based on a boosted fission design.

The original Babur-1 ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCM) has been test-launched nearly a dozen times and is likely to be operational with the armed forces. Its road-mobile launcher appears to be a unique five-axle TEL with a three-tube box launcher that is different than the quadruple box launcher used for static display. At different times, the Pakistani government has reported the range to be 600 km (372 miles) and 700 km (435 miles) (ISPR 2011a, 2012a, 2012b), but the US intelligence community sets the range much lower, at 350 km (217 miles) (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020).

Pakistan appears to be upgrading the original Babur-1 missiles into Babur-1A missiles by upgrading their avionics and navigation systems to enable target engagement both on land and at sea. Following the system’s most recent test in February 2021, the Pakistani military stated that the Babur-1A’s range was 450 km (ISPR 2021e).

Pakistan is also developing an enhanced version of the Babur known as the Babur-2 or Babur-1B GLCM.[xiii] The weapon has been test-launched at least two times: in December 2016 and April 2018 (ISPR 2016b, 2018a). In March 2020, Indian news media reported that the Babur-2/Babur-1B had failed two other tests, in April 2018 and March 2020; however, this was not confirmed by Pakistan (Gupta 2020). With a physical appearance and capabilities similar to those of the Babur, the Babur-2/Babur-1B apparently has an extended range of 700 km (435 miles), and “is capable of carrying various types of warheads” (ISPR 2016b, 2018a). The fact that both the Babur-1 and the “enhanced” Babur-2/Babur-1B have been noted as possessing a range of 700 km indicates that the range of the initial Babur-1 system was likely shorter. NASIC has not released information on an enhanced system. After the first test in 2016, the Pakistani government noted that the system is “an important force multiplier for Pakistan’s strategic defence” (ISPR 2016b).

Babur TELs have been fitting out at the National Development Complex for several years and have recently been seen at the Akro garrison northeast of Karachi. The garrison includes a large enclosure with six garages that have room for 12 TELs and a unique underground facility that is probably used to store the missiles.[xiv]

Pakistan is also developing a sea-launched version of the Babur known as Babur-3. The weapon is still in development and has been test-launched twice: On January 9, 2017, from “an underwater, mobile platform” in the Indian Ocean (ISPR 2017c); and on March 29, 2018 from “an underwater dynamic platform” (ISPR 2018b). The Babur-3 is said to be a sea-based variant of the Babur-2 GLCM, and to have a range of 450 km (279 miles) (ISPR 2017c).

The Pakistani government says the Babur-3 is “capable of delivering various types of payloads … [that] … will provide Pakistan with a Credible Second Strike Capability, augmenting deterrence,” and described it as “a step towards reinforcing [the] policy of credible minimum deterrence” (ISPR 2017c). The Babur-3 will most likely be deployed on the diesel-electric Agosta class submarines (Khan 2015). In April 2015, the Pakistani government approved the purchase of right air-independent propulsion-powered submarines from China, the first four of which are due in 2022-2023 (Khan 2019). It is possible that these new submarines, which will be called the Hangor-class, could eventually be assigned a nuclear role with the Babur-3 submarine-launched cruise missile.

Once it becomes operational, the Babur-3 will provide Pakistan with a triad of nuclear strike platforms from ground, air, and sea. The Pakistani government said the Babur-3 was motivated by a need to match India’s nuclear triad and the “nuclearization of [the] Indian Ocean Region” (ISPR 2018b). The Pakistani government also noted that Babur-3’s stealth technologies would be useful in the “emerging regional Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) environment” (ISPR 2017c).

The future submarine-based nuclear capability is managed by Headquarters Naval Strategic Forces Command (NSFC), which the government said in 2012 would be the “custodian of the nation’s 2nd strike capability” to “strengthen Pakistan’s policy of Credible Minimum Deterrence and ensure regional stability” (ISPR 2012c). Kidwai in 2015 publicly acknowledged the need for a sea-based second-strike capability and said it “will come into play in the next few years” (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2015, 16).

Pakistan also appears to be developing a variant of the Babur cruise missile, known as the Harbah, that can be carried by surface vessels. Pakistan describes the system as “a surface-to-surface anti-ship missile with land attack capability” (ISPR 2018d). Although Pakistan did not state the system’s range after either of its 2018 or 2019 tests, official photos of the system in-flight bear a strong resemblance to the Babur (ISPR 2018d; Rahmat 2019). It is unknown at this time if the Harbah will be dual-capable.

No comments:

Post a Comment