By Simon Worrall

PUBLISHED AUGUST 26, 2017

Half a million earthquakes occur worldwide each year,

according to an estimate by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Most are

too small to rattle your teacup. But some, like the 2011 quake off the

coast of Japan or last year’s disaster in Italy, can level high-rise

buildings, knock out power, water and communications, and leave a

lifelong legacy of trauma for those unlucky enough to be caught in them.

In

the U.S., the focus is on California’s San Andreas fault, which

geologists suggest has a nearly one-in-five chance of causing a major

earthquake in the next three decades. But it’s not just the faults we

know about that should concern us, says Kathryn Miles, author of

Quakeland: On the Road to America’s Next Devastating Earthquake. As she

explained when National Geographic caught up with her at her home in

Portland, Maine, there’s a much larger number of faults we don’t know

about—and fracking is only adding to the risks.

When it comes to earthquakes, there is really only one question everyone wants to know: When will the big one hit California?

That’s

the question seismologists wish they could answer, too! One of the most

shocking and surprising things for me is just how little is actually

known about this natural phenomenon. The geophysicists, seismologists,

and emergency managers that I spoke with are the first to say, “We just

don’t know!”

What

we can say is that it is relatively certain that a major earthquake

will happen in California in our lifetime. We don’t know where or when.

An earthquake happening east of San Diego out in the desert is going to

have hugely different effects than that same earthquake happening in,

say, Los Angeles. They’re both possible, both likely, but we just don’t

know.

One

of the things that’s important to understand about San Andreas is that

it’s a fault zone. As laypeople we tend to think about it as this single

crack that runs through California and if it cracks enough it’s going

to dump the state into the ocean. But that’s not what’s happening here.

San Andreas is a huge fault zone, which goes through very different

types of geological features. As a result, very different types of

earthquakes can happen in different places.

There

are other places around the country that are also well overdue for an

earthquake. New York City has historically had a moderate earthquake

approximately every 100 years. If that is to be trusted, any moment now there will be another one, which will be devastating for that city.

As

Charles Richter, inventor of the Richter Scale, famously said, “Only

fools, liars and charlatans predict earthquakes.” Why are earthquakes so

hard to predict? After all, we have sent rockets into space and plumbed

the depths of the ocean.

You’re

right: We know far more about distant galaxies than we do about the

inner workings of our planet. The problem is that seismologists can’t

study an earthquake because they don’t know when or where it’s going to

happen. It could happen six miles underground or six miles under the

ocean, in which case they can’t even witness it. They can go back and do

forensic, post-mortem work. But we still don’t know where most faults

lie. We only know where a fault is after an earthquake has occurred. If

you look at the last 100 years of major earthquakes in the U.S., they’ve

all happened on faults we didn’t even know existed.

Earthquakes 101

Earthquakes

are unpredictable and can strike with enough force to bring buildings

down. Find out what causes earthquakes, why they’re so deadly, and

what’s being done to help buildings sustain their hits.

Fracking

is a relatively new industry. Many people believe that it can cause

what are known as induced earthquakes. What’s the scientific consensus?

The

scientific consensus is that a practice known as wastewater injection

undeniably causes earthquakes when the geological features are

conducive. In the fracking process, water and lubricants are injected

into the earth to split open the rock, so oil and natural gas can be

retrieved. As this happens, wastewater is also retrieved and brought

back to the surface.

You Might Also Like

Different

states deal with this in different ways. Some states, like

Pennsylvania, favor letting the wastewater settle in aboveground pools,

which can cause run-off contamination of drinking supplies. Other

states, like Oklahoma, have chosen to re-inject the water into the

ground. And what we’re seeing in Oklahoma is that this injection is

enough to shift the pressure inside the earth’s core, so that daily

earthquakes are happening in communities like Stillwater. As our

technology improves, and both our ability and need to extract more

resources from the earth increases, our risk of causing earthquakes will

also rise exponentially.

After

Fukushima, the idea of storing nuclear waste underground cannot be

guaranteed to be safe. Yet President Trump has recently green-lighted

new funds for the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada. Is that wise?

The

issue with Fukushima was not about underground nuclear storage but it

is relevant. The Tohoku earthquake, off the coast of Japan, was a

massive, 9.0 earthquake—so big that it shifted the axis of the earth and

moved the entire island of Japan some eight centimeters! It also

created a series of tsunamis, which swamped the Fukushima nuclear power

plant to a degree the designers did not believe was possible.

Here

in the U.S., we have nuclear plants that are also potentially

vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis, above all on the East Coast,

like Pilgrim Nuclear, south of Boston, or Indian Point, north of New

York City. Both of these have been deemed by the USGS to have an

unacceptable level of seismic risk. [Both are scheduled to close in the

next few years.]

Yucca

Mountain is meant to address our need to store the huge amounts of

nuclear waste that have been accumulating for more than 40 years.

Problem number one is getting it out of these plants. We are going to

have to somehow truck or train these spent fuel rods from, say, Boston,

to a place like Yucca Mountain, in Nevada. On the way it will have to go

through multiple earthquake zones, including New Madrid, which is

widely considered to be one of the country’s most dangerous earthquake

zones.

Yucca

Mountain itself has had seismic activity. Ultimately, there’s no great

place to put nuclear waste—and there’s no guarantee that where we do put

it is going to be safe.

The psychological and emotional effects of an earthquake are especially harrowing. Why is that?

This

is a fascinating and newly emerging subfield within psychology, which

looks at the effects of natural disasters on both our individual and

collective psyches. Whenever you experience significant trauma, you’re

going to see a huge increase in PTSD, anxiety, depression, suicide, and

even violent behaviors.

What

seems to make earthquakes particularly pernicious is the surprise

factor. A tornado will usually give people a few minutes, if not longer,

to prepare; same thing with hurricanes. But that doesn’t happen with an

earthquake. There is nothing but profound surprise. And the idea that

the bedrock we walk and sleep upon can somehow become liquid and mobile

seems to be really difficult for us to get our heads around.

Psychologists

think that there are two things happening. One is a PTSD-type loop

where our brain replays the trauma again and again, manifesting itself

in dreams or panic attacks during the day. But there also appears to be a

physiological effect as well as a psychological one. If your readers

have ever been at sea for some time and then get off the ship and try to

walk on dry land, they know they will look like drunkards. [Laughs] The

reason for this is that the inner ear has habituated itself to the

motion of the ship. We think the inner ear does something similar in the

case of earthquakes, in an attempt to make sense of this strange,

jarring movement.

After

the Abruzzo quake in Italy, seven seismologists were actually tried and

sentenced to six years in jail for failing to predict the disaster.

Wouldn’t a similar threat help improve the prediction skills of American

seismologists?

[Laughs]

The scientific community was uniform in denouncing that action by the

Italian government because, right now, earthquakes are impossible to

predict. But the question of culpability is an important one. To what

degree do we want to hold anyone responsible? Do we want to hold the

local meteorologist responsible if he gets the weather forecast wrong?

[Laughs]

What

scientists say—and I don’t think this is a dodge on their parts—is,

“Predicting earthquakes is the Holy Grail; it’s not going to happen in

our lifetime. It may never happen.” What we can do is work on early

warning systems, where we can at least give people 30 or 90 seconds to

make a few quick decisive moves that could well save your life. We have

failed to do that. But Mexico has had one in place for years!

There is some evidence that animals can predict earthquakes. Is there any truth to these theories?

All

we know right now is anecdotal information because this is so hard to

test for. We don’t know where the next earthquake is going to be so we

can’t necessarily set up cameras and observe the animals there. So we

have to rely on these anecdotal reports, say, of reptiles coming out of

the ground prior to a quake. The one thing that was recorded here in the

U.S. recently was that in the seconds before an earthquake in Oklahoma

huge flocks of birds took flight. Was that coincidence? Related? We

can’t draw that correlation yet.

One

of the fascinating new approaches to prediction is the MyQuake app.

Tell us how it works—and why it could be an especially good solution for

Third World countries.

The

USGS desperately wants to have it funded. The reluctance appears to be

from Congress. A consortium of universities, in conjunction with the

USGS, has been working on some fascinating tools. One is a dense network

of seismographs that feed into a mainframe computer, which can take all

the information and within nanoseconds understand that an earthquake is

starting.

MyQuake

is an app where you can get up to date information on what’s happening

around the world. What’s fascinating is that our phones can also serve

as seismographs. The same technology that knows which way your phone is

facing, and whether it should show us an image in portrait or landscape,

registers other kinds of movement. Scientists at UC Berkeley are

looking to see if they can crowd source that information so that in

places where we don’t have a lot of seismographs or measuring

instruments, like New York City or Chicago or developing countries like

Nepal, we can use smart phones both to record quakes and to send out

early warning notices to people.

You traveled all over the U.S. for your research. Did you return home feeling safer?

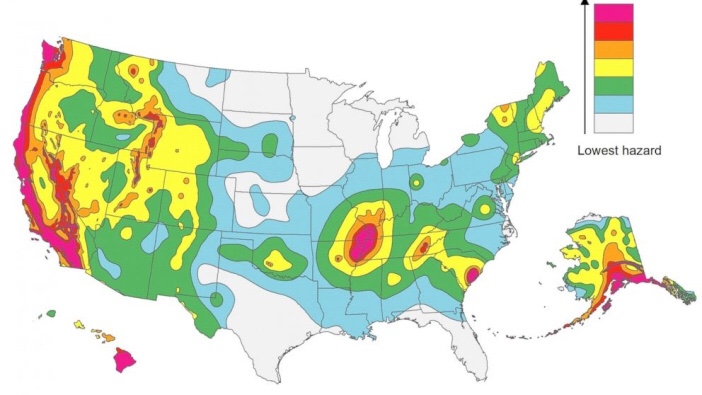

I

do not feel safer in the sense that I had no idea just how much risk

regions of this country face on a daily basis when it comes to seismic

hazards. We tend to think of this as a West Coast problem but it’s not!

It’s a New York, Memphis, Seattle, or Phoenix problem. Nearly every

major urban center in this country is at risk of a measurable

earthquake.

What

I do feel safer about is knowing what I can do as an individual. I hope

that is a major take-home message for people who read the book. There

are so many things we should be doing as individuals, family members, or

communities to minimize this risk: simple things from having a go-bag

and an emergency plan amongst the family to larger things like building

codes.

We

know that a major earthquake is going to happen. It’s probably going to

knock out our communications lines. Phones aren’t going to work, Wi-Fi

is going to go down, first responders are not going to be able to get to

people for quite some time. So it is beholden on all of us to make sure

we can survive until help can get to us.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

No comments:

Post a Comment