Russia Is Developing Some Scary Nuclear Weapons. It Has To Give Them Up To Save New START.

With the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty now officially dead, the fate of the New START treaty–and with it, much of the world’s remaining nuclear arms control architecture–continues to hang in the balance. Earlier this week, the Pentagon revealed what it would take to save New START– and the Kremlin isn’t going to like it.

In a recent interview given to Fox News, US Defense Secretary Mark Esper conditioned the potential extension of New START, set to expire in February 2021, on the inclusion of Russia’s latest nuclear-capable weapons and hypersonic delivery systems: “If there is going to be an extension of the New START, then we need to make sure that we include all these new weapons that Russia is pursuing… “Right now, Russia has possibly nuclear-tipped cruise missiles, INF-range (range stipulated by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Weapons Treaty) cruise missiles facing toward Europe.”

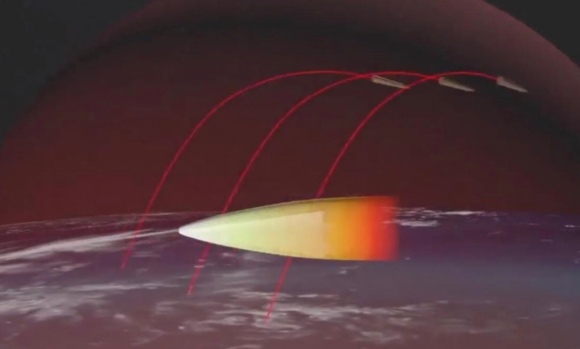

But what exactly are these “new weapons,” and do they fall under New START’s jurisdiction? With Russia’s Poseidon Thermonuclear drones still in testing and reportedly up to eight years away from entering service, the arms control discussion is currently centered around two of the weapons unveiled at Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2018 annual annual state-of-the-nation address: the avangard hypersonic boost-glide missile system, and the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal nuclear-capable, long-range air-to-surface ballistic missile.

Avangard’s treaty classification is all but an open-and-shut case. Not only is it designed to carry missiles already regulated by New START, but avangard itself falls under New START’s definition of a re-entry vehicle– that is, an object “that can survive reentry through the dense layers of the Earth’s atmosphere and that is designed for delivering a weapon to a target or for testing such a delivery.”

Meanwhile, the Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile is more of a grey area. In of itself, it likely falls outside of New START’s jurisprudence– the same, however, cannot be said of its long-range carrier. Experts argue that there is a strong basis for classifying the upcoming, kinzhal-compatible Tu-22M3M as an “undeclared heavy bomber” under the treaty’s classification system, especially if it can achieve the treaty-specified range of over 8,000 kilometers with aerial refueling.

Russian officials and defense commentators have gone out of their way to deny that any of the above weapons fall under New START’s limitation guidelines. Despite barely making a dent in the total allowed limit of 800 deployed or non deployed strategic delivery vehicles, Russia’s latest weapons have become a major point of contention in the ongoing debate over New START’s extension because of the treaty’s enforcement implications; namely, the treaty requires Moscow to notify Washington whenever it deploys or tests Avangard. Moreover, the treaty’s sanctioned satellite tracking and yearly onsite inspections would allow the US to continuously monitor the production, location, and activity of every avangard unit.

Prominent Russian defense commentators believe that this level of forced transparency would hamper the efficacy of Russia’s nuclear deterrent and undermine future Russian weapon research and defense efforts.

The Kremlin, for its part, sees Esper’s proposal as a nonstarter. Russia’s ambassador to the US Anatoly Antonov has stated in no uncertain terms that Russia not only denies the applicability of New START to any of the weapons unveiled at Putin’s 2018 address, but rejects all plans to broaden the scope of New START to cover any new weapons whatsoever: “we have to stick with the provisions of the Treaty,” Antonov said at the Carnegie Endowment’s nuclear policy conference in March of 2019.

Mark Episkopos is a frequent contributor to The National Interest and serves as research assistant at the Center for the National Interest. Mark is also a PhD student in History at American University.

No comments:

Post a Comment