Dress Rehearsal for Armageddon: How Cities Plan for a Nuclear Attack

By Andrew Karam

Then everyone takes their turn talking. The police

will discuss how they intend to secure the city, getting people to

safety, keeping them out of areas that are dangerously radioactive, and

trying to maintain civil order. The fire department is going to have

fires to put out, people to rescue, and will begin setting up

decontamination stations.

But the nature of nuclear

attacks makes these daunting tasks even more difficult. For example, the

Health Department might need to figure out exactly where the winds have

taken the plume, so it won’t be safe for anyone

to be outside, including first responders. If you’re caught in the

plume’s centerline, the area where the fallout is most dangerous, you’re

going to get a fatal dose of radiation in a matter of minutes. So now

both Fire and Police know that they can’t immediately spring into

action. Instead, they have to wait for the plume to settle out before

they can start the evacuation.

The initial plume is only a

small part of the problem. In close proximity to a 5 kT bomb, virtually

every building within about a half-mile radius will collapse, shattered

by the force of the explosion, and create rubble as much as 100 feet

deep. Meanwhile, many areas will be remain engulfed in flame. In

Hiroshima, this ensuing mass fire was as deadly as the radiation.

So during the TTX, those

around the table will go through the plans to see how their agency can

respond – and to see if they can help to make things better (or at least

help keep them from getting worse). They look for holes in the plans –

what do we need to do that hasn’t been address? What have we been

assigned that we just can’t do? Do we have the equipment, personnel, and

training to carry out our responsibilities? And are we doing everything

we can to keep the public and the emergency responders safe?

The result of these

exercises is usually a lot of sober faces sitting around a table.

Knowing that in real life these decisions could affect the lives of

millions of people. It’s a sobering experience, and when talking with

others, you quickly learn that they feel the same way.

The Execution

Once the local, state and

federal representatives step in, and the plan is analyzed from every

conceivable angle, it’s time for the last step—boots-on-the-ground

exercises.

Every so often you’ll hear about nuclear terrorism exercises in Virginia Beach or New York City. Although conspiracy theorists may dream up more sinister motives,

these tests are absolutely necessary. Until this moment, all the

experts have really done is to write and talk by people who haven’t been

in the field for years. Now is the time to put workers into their

protective clothing, give them radiation meters, set up decon stations,

and do everything else we can to prepare for the worst.

This is the penultimate

test—with the ultimate test being something you hope you never have to

do. Field personnel make sure they can find their equipment, operate it

under realistic conditions, and answer minuscule but deadly important

questions like if the switches on a radiation meter are too small to

operate in protective gear and if we can really set up a decon tent in only 2 hours.

If everything goes

smoothly, then the next step is making the plan better, faster, and as

flexible as possible. If the opposite is true, then it’s back to the

step one, this time armed with many lessons learned.

All this seems like a flurry of planning that can come together over a few weeks, but sometimes this process can take years

to accomplish. One plan I personally worked on took over five years to

hash out, another two years to set up a series of TTX exercises, and few

more to revise the plan. After all, these agencies do lots of other important things every day, but nuclear preparedness scenarios continue to be conducted across the country

The Survival Strategy

It goes without saying

that a nuclear attack is a horrific circumstance, but it can be survived

at distances of less than a mile from ground zero, depending on the

strength of the explosion. Of course, there are a lots of variables, but

you shouldn’t assume that a nuclear attack means instant and

unavoidable death.

Strangely, fleeing also

isn’t necessarily your best option. If you see a bright flash and

mushroom cloud and turn to run the other way, half an hour later you

might sustain a lethal dose of radiation—all depending on which way the

wind is blowing.

The very best thing you

can do is go into the nearest stable building and stay there until

you’re told it’s safe to leave. That might be in a few hours (if the

plume went in another direction) or it might not be for a few days. But

unless you’re a radiation safety professional with your own instruments,

you have no way of knowing if it’s safe to go outside or even know

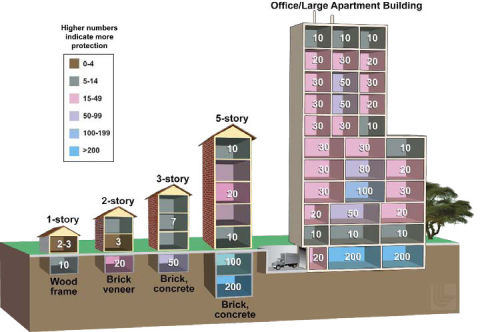

which direction to evacuate. Remember, vehicles offer no protection, so you’ve got to be in a building—the larger the better.

Once inside, stay toward

the center of the building because fallout can still expose through

walls. So the further from the exterior walls you’re staying, the lower

the radiation dose will be. Stay on a lower floor or in the basement,

and fallout that would kill you in a matter of hours can be easily

survived if you find the right shelter.

You’re also going to be in

dire need of uncontaminated food and water. You can fill the bathtub

(if you think of it), take water from the toilet tank, drink whatever

you have in your refrigerator as well as any bottled liquids you might

have in the basement or garage. But most people can survive for a few

days without drinking at all, and even longer on a relatively minimal

amount of water. So you don’t need to keep a month of water on hand at

all times.

The Navy has a saying that

“failing to plan is planning to fail.” Although a nuclear attack

remains unlikely, it’s a deadly serious possibility where the right

information can save your life. It’s a plan you hope to never have to

use, but one that’s undeniably necessary.