Summary

Last week Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Qatar, and Russia reached an historic agreement to cap oil production at mid-January levels.

Absent an improbable cut in global production, oil prices will stay low as the current glut lingers on.

One of the reasons Saudi Arabia orchestrated a drop in prices was to challenge the nascent U.S. shale revolution.

Coupled with sanctions wreaking havoc on the Kremlin’s budget, the longer Saudi Arabia can keep prices down, the more it will compound Russia’s economic pain.

Saudi Arabia is also using low oil prices as a means of upending on its traditional rival, Iran.

Absent an improbable cut in global production, oil prices will stay low as the current glut lingers on.

One of the reasons Saudi Arabia orchestrated a drop in prices was to challenge the nascent U.S. shale revolution.

Coupled with sanctions wreaking havoc on the Kremlin’s budget, the longer Saudi Arabia can keep prices down, the more it will compound Russia’s economic pain.

Saudi Arabia is also using low oil prices as a means of upending on its traditional rival, Iran.

Last week Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Qatar, and Russia reached an historic agreement

to cap oil production at mid-January levels. The pact – the first

between OPEC and a non-OPEC member in 15 years – aims to halt the

precipitous fall in oil prices that has wreaked havoc around the world.

While news of the deal sparked some optimism, any

bullishness quickly faded as reality began to set in: the deal will not

take a single barrel off the market. Absent an improbable cut in global

production, oil prices will stay low as the current glut lingers on.

The decision to freeze rather than cut production seems

counterintuitive; producers have been under incredible financial strain,

with some seeking assistance

in a bid to keep their economies afloat. But for Saudi Arabia, the

chief architect of the current crisis, there are several reasons for

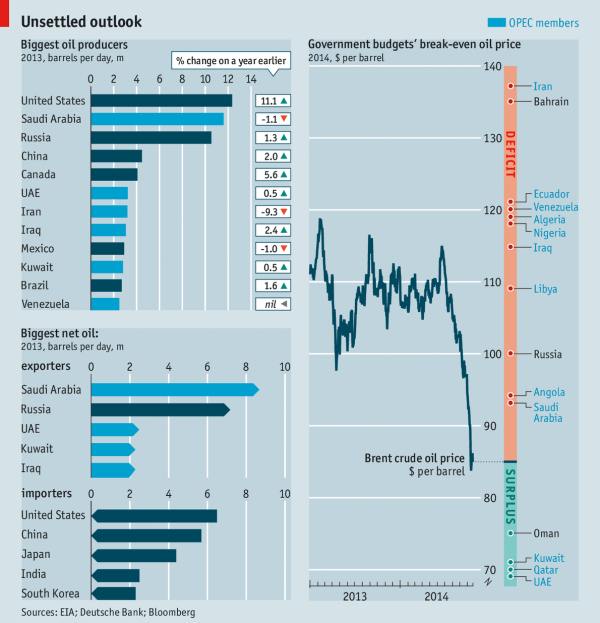

keeping prices low. These include: halting the U.S. shale revolution, making Russia pay for its Syria incursion, and undercutting Iran and Iraq.

With these strategies now beginning to bear fruit,

Riyadh will resist calls to cut production. Moreover, without OPEC

cooperation, other producers will also pump at near record levels,

desperate not to concede market share. Low oil prices will therefore

continue, at least for the foreseeable future.

Countering the U.S. shale revolution

One of the reasons Saudi Arabia orchestrated a drop in

prices was to challenge the nascent U.S. shale revolution. The next few

years will see the U.S. set to become the world’s largest producer,

while reports also suggest its shale output could double from 4 to 8 million barrels per day by 2035.

This may seem insignificant; the IAE forecasts worldwide demand at around 96 million barrels this year. But analysts claim that even a 5% cut

in global output – around 4.8 million barrels – would raise prices by

between 50 to 100% today. So, shale will almost certainly heap downward

pressure on prices in the long term.

Just as important, the limited time and money needed to

construct wells mean they can be capped on and off relatively easily.

This provides Washington a flexible lever to balance price shocks and

weakens Saudi Arabia’s influence as a “swing” producer.

Not surprisingly, Saudi Arabia has plotted shale’s downfall.

With the high costs of shale production, Riyadh figured a dramatic fall

in prices would drive these new players out of business, thereby

preserving the status quo.

The strategy has produced mixed results. Despite dozens

of companies going bust, many have proved resistant, tightening belts

and digging in their heels. Slowly, however, these companies are

succumbing to market forces, with a wave of bankruptcies expected this

year.

While many doubt Saudi Arabia’s ability to hold off the

shale revolution indefinitely – especially since procuring shale is

becoming much cheaper – the House of Saud is unlikely to cut production

soon, given the relief it would offer its U.S competitors.

Reacting to Russia’s incursion into Syria

Vladimir Putin’s incursion into Syria in September last

year has changed the facts on the ground, entrenching Bashar al-Assad’s

regime and diminishing the influence of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf

nations. Whereas Assad’s rule had looked shaky at the war’s start,

Moscow’s involvement now all but ensures his survival.

Furthermore, as Russia continues to strike at opposition

rebels, many of them sponsored by Saudi Arabia, Riyadh’s clout is

beginning to fade. Moreover, as its influence in Syria wanes, so too

will its role in further peace talks and discussions about the country’s

future.

Dismayed at what

they perceive as U.S. inaction in the face of Russian aggression in

Aleppo and other flash points in the north, Saudi officials are becoming

increasingly frustrated. Though the de facto OPEC leader is

unlikely to get involved militarily without Washington’s consent,

keeping prices low is one way to hurt Moscow’s fragile economy.

Coupled with sanctions wreaking havoc on the Kremlin’s

budget, the longer Saudi Arabia can keep prices down, the more it will

compound Russia’s economic pain. In fact, Russia’s finance minister,

Anton Siluanov, recently claimed that the country needs $82 oil to

balance the budget, with many analysts claiming that a default is now a

possibility.

That might not change Putin’s calculations in Syria, but

low oil prices will at least serve a costly reminder that Russia’s

actions come with consequences.

Undercutting Iran and Iraq

Saudi Arabia is also using low oil prices as a means of upending on its traditional rival, Iran. True,

the Saudi economy is heavily reliant on oil, with shipments accounting

for 90 percent of its export earnings and 80 percent of government

revenues. But it still enjoys a favorable financial position over its

adversary across the Persian Gulf, with greater reserves and a smaller

debt ratio. Meanwhile, Iran needs higher oil prices to break even.

In terms of regional influence, therefore, Saudi Arabia

is likely to keep oil prices low in a bid to outlast Iran. Eventually,

Riyadh hopes the financial pressure will mean Iran is unable to maintain

its proxies in Syria, Yemen and elsewhere.

Having made huge military and diplomatic strides

recently, which includes a recent nuclear deal with the U.S., Tehran may

be forced to adopt a less expansive foreign policy, allowing the Saudis

to reconfigure alliances in the region and regain much of their lost

influence.

Similarly, Riyadh sees low prices as a means of further

destabilizing the impotent Shia regime in Iraq, which has been an

Iranian ally since the overthrow of Saddam. The alliance between the two

has stoked Saudi fears of a coming “Shia Crescent”, with Saudi Arabia’s

rulers keen to ensure Iran’s neighbor remains bitterly fragmented. As

an added bonus, in the longer term, continued instability may also mean

Iraq is unable to develop its remaining oil reserves.

No comments:

Post a Comment