Why Hillary Clinton Is Probably Going to Win the 2016 Election

April 12, 2015Jonathan Chait

Unless the economy goes into a recession over the next year and a half, Hillary Clinton is probably going to win the presidential election. The United States has polarized into stable voting blocs, and the Democratic bloc is a bit larger and growing at a faster rate.

Of

course, not everybody who follows politics professionally believes

this. Many pundits feel the Democrats’ advantage in presidential

elections has disappeared, or never existed. “The 2016 campaign is starting on level ground,” argues David Brooks, echoing a similar analysis by John Judis.

But the evidence for this is quite slim, and a closer look suggests

instead that something serious would have to change in order to prevent a

Clinton victory. Here are the basic reasons why Clinton should be considered a presumptive favorite:

1. The Emerging Democratic Majority is real.

The major disagreement over whether there is an “Emerging Democratic

Majority” — the thesis that argues that Democrats have built a

presidential majority that could only be defeated under unfavorable

conditions — centers on an interpretive disagreement over the 2014

elections. Proponents of this theory dismiss the midterm elections as a

problem of districting and turnout; Democrats have trouble rousing their

disproportionately young, poor supporters to the polls in a

non-presidential year, and the tilted House and Senate map further

compounded the GOP advantage.

Skeptics of the theory instead believe that the 2014 midterms were, as Judis put it, “not an isolated event but rather the latest manifestation of a resurgent Republican coalition.”

Voters, they argue, are moving toward the Republican Party, and may

continue to do so even during the next presidential election.

It

has been difficult to mediate between the two theories, since the

outcome at the polls supports the theory of both the proponents and the

skeptics of the Emerging Democratic Majority theory equally well.

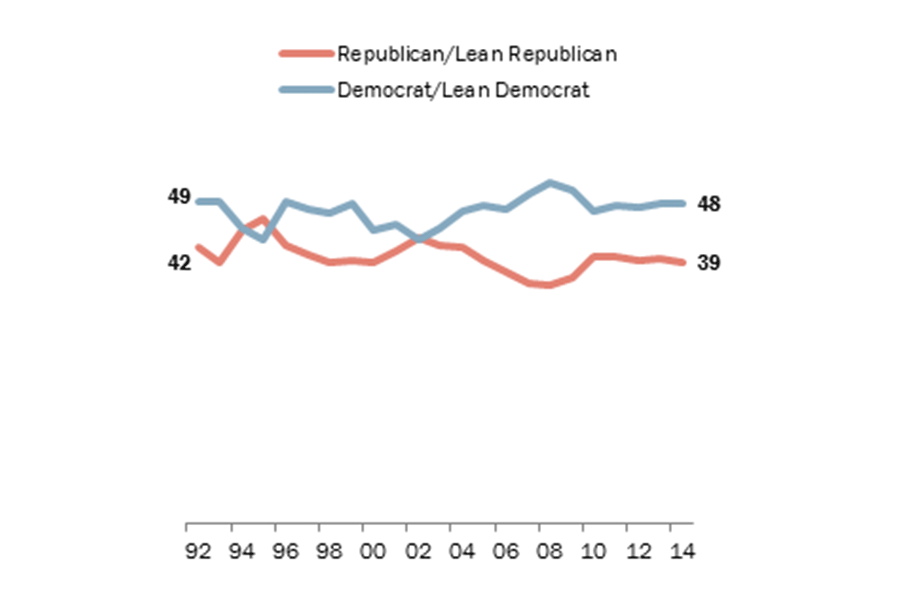

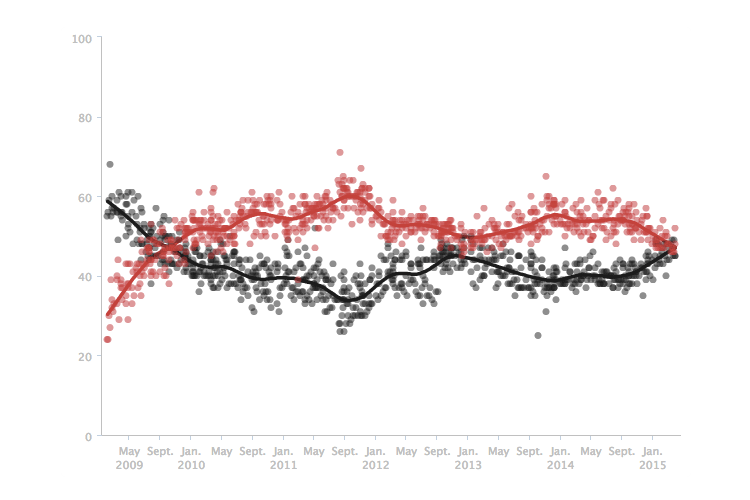

A Pew survey released

this week gives us the best answer. Pew is the gold standard of

political polling, using massive surveys, with high numbers of

respondents and very low margins of error. Pew’s

survey shows pretty clearly that there was not a major change in public

opinion from the time of Obama’s reelection through the 2014 midterms:

Of

course, Pew is not surveying actual voters. It’s surveying all adults.

But that is the point. What changed between 2012 and 2014 was not public

opinion, but who showed up to vote.

2. No, youngsters are not turning Republican.

The Emerging Democratic Majority thesis places a lot of weight on

cohort replacement: Republicans fare best with the oldest voters, and

Democrats with the youngest, so every new election cycle incrementally

tilts the electoral playing field toward the Democrats.

Skeptics

have pushed back by claiming that the youngest voters — the ones

entering their voting years since 2008 — are turning back toward the

Republican Party. Their main evidence has been pollings of millennial

voters by the Harvard Institute of Politics. Conservatives have given

these results a great deal of

attention — it suggests that the youngest voters, disillusioned by the

Obama administration, have abandoned the liberal tendencies of their

older brothers and sisters. But Harvard’s polling has not held up well;

it predicted millennial voters would support a Republican Congress in 2014, which turned out to be extremely inaccurate.

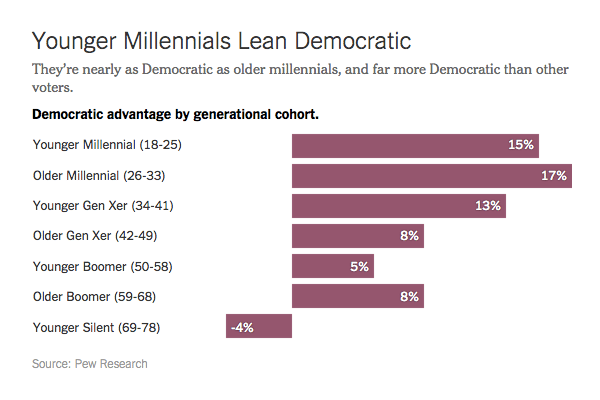

Pew’s more recent survey combs through the data and throws more cold water on the “younger millennials” thesis. As Nate Cohn notices, younger millennials lean Democratic at nearly the same rate as older ones:

(Cohn

does note that younger nonwhite millennials seem less Democratic than

older nonwhite millennials, but young whites are far more Democratic

than older ones, making the trade somewhat of a wash.)

3. Clinton isn’t that unpopular.

A more recent line of thought has settled on Clinton’s limits as a

candidate. It is probably true that she lacks Obama’s talents as a

communicator and a campaign organizer. A recent Quinnipiac poll showing

her struggling in Iowa and Colorado attracted wide media attention and

seemed to confirm that the email scandal has tarnished Clinton’s

national image.

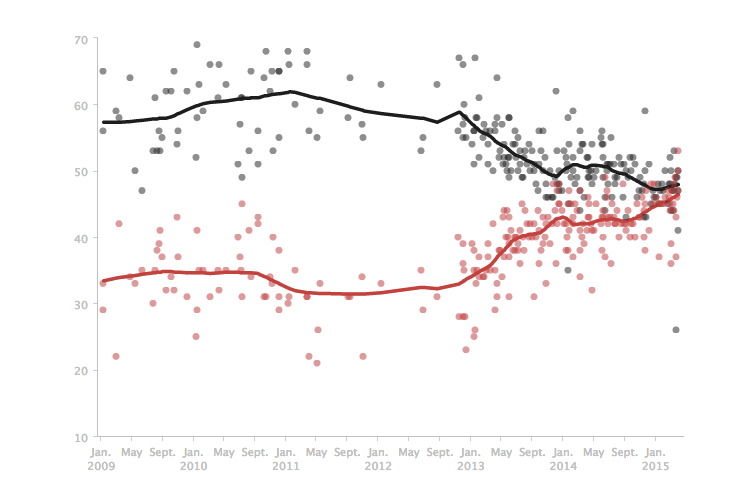

It

is true that Clinton has, inevitably, lost much of the popularity she

won when she was serving as secretary of State and largely removed from

partisan politics. Nonpartisan figures can attract broad support, while

people engaged in political fights tend to revert toward the mean.

Clinton’s support is, as it has been through most of her career, closely divided:

On the other hand, Republicans are much less popular. Jeb Bush, who is probably the best known of the Republican contenders, has much worse favorable ratings:

So

there is little reason to think Clinton’s personal unpopularity will

hold her back in a race against a Republican who is likely to have no

more personal appeal, and possibly a lot less.

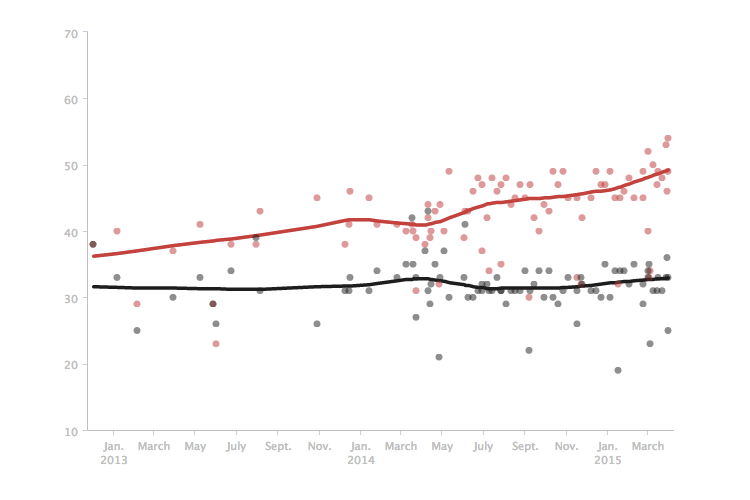

4. Obama is trending up.

One major question looming over the next election is whether the public

feels satisfied with the Democrats’ policy direction or wants to give

Republicans a chance. Importantly, President Obama’s job approval

ratings have recovered since the midterm elections, when his net approval stood at minus ten, to about minus three. His approval ratings on handling the economy have risen even more sharply. Approval of Obama’s economic job performance has actually reached parity with disapproval for the first time since 2009:

If

the economy continues to expand between now and the 2016 election,

Obama’s approval rating will probably rise a little higher. In the

modern political world, strong popularity is not necessary to win; Obama

won reelection with approval ratings below 50 percent. Voters make

comparative choices, and all a candidate needs is to be superior to the

alternative. But the economy is currently on a course, barring a

slowdown, to leave the incumbent party in a stronger position.

5. Is it time for a change? The

one remaining ground for Republican optimism is the possibility that

voters will decide three straight presidential terms for the Democratic

Party is too much. Many political scientists (such as Alan Abramowitz)

believe this exhaustion factor is real; after a second term, voters

grow increasingly restless with the in-party and are more likely to

decide it’s time for a change. If this is true, Clinton may face

headwinds even in an otherwise favorable landscape.

It

may well be true. But there are reasons to doubt it. One reason is that

models that detect voter impatience are based on a very small number of

data points. Since World War II, there have been eight presidential

elections in which the incumbent party has held office for two terms or

more. It’s hard to draw definitive conclusions from such a limited

number of events.

A

second reason is that nearly all of those elections took place in a

very different kind of party system. The 20th century was a time of

loose-knit parties with a great deal of ideological overlap. There were

liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats, which created large

constituencies to swing back and forth. Democrats won more than 60

percent of the vote in the 1964 election, and then Republicans did the

same eight years later. That made sense in a world where the two parties

seemed to share a lot of common assumptions. Voters who supported

Lyndon Johnson in 1964 weren’t crazy to switch to Richard Nixon in 1972;

Nixon had established the Environmental Protection Agency and supported

universal health care and a basic income.

The

polarized electorate of today is a different place, and voters may not

act the same way as they used to. There are fewer swing voters, and

therefore conditions like a third straight term, or even a severe

recession, may not budge as many of them from their normal partisan

habits. We don’t know how deeply the partisan split has hardened into

place; each party seems to be able to count on the support of at least

45 percent of the voters regardless of what is happening in the world.

6. There’s no alternative.

All of the above brings us back to the central challenge facing

Clinton. She cannot promise her supporters a dramatic change or new

possibilities; she is personally too familiar, and the near certainty of

at least one Republican-controlled chamber of Congress suggests

continued legislative stalemate. Her worry is that ennui sets in among

the base and yields a small electorate more like the kind that shows up

at the midterms, which is an electorate Republicans can win.

The argument for Clinton in 2016 is that she is the candidate of the only major American political party not run by lunatics. There is only one choice for voters who want a president who accepts climate science and rejects voodoo economics, and whose domestic platform would not engineer the largest upward redistribution of resources in

American history. Even if the relatively sober Jeb Bush wins the

nomination, he will have to accommodate himself to his party’s

barking-mad consensus. She is non-crazy America’s choice by default. And

it is not necessarily an exciting choice, but it is an easy one, and a

proposition behind which she will probably command a majority.

No comments:

Post a Comment