Sadr-linked Twitter account slams protesters’ slogan as unpatriotic | | AW

Iraqi Twitter user “@trend_althuraa” posted: “We want a homeland devoid of your political parties. We want a country free of your corruption. We want a homeland free of your militias. We want to restore the prestige of the state after you hijacked everything, including our dreams.”

While Iraqis’ reactions varied, most users criticised the political class and its management of state affairs.

Twitter user “@TISHRIN” wrote, “Do you know why the slogan # We_want_a_homeland bothers them? It is because they are fearing to lose their privileges.”

“56 deputies, 6 ministries, the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Speaker of Parliament, 4 governors, more than 120 general directors, armed militia, ambassadors and agents. What reform are you talking about? Give up your self-proclaimed role in reforming people and reform yourselves,” he added.

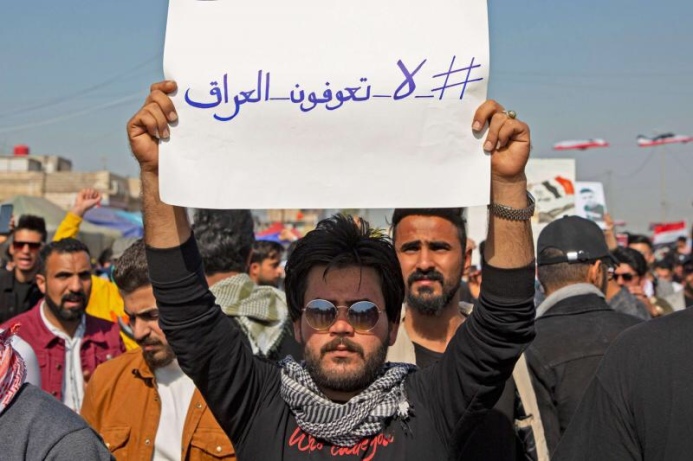

Online campaigns targeting the Tishrinya, one of the appellations of the Iraqi protest movement, have grown on social media websites. These campaigns, aimed at dispiriting and intimidating protesters, are allegedly being conducted by Sadr’s electronic army and supported Iran-backed militias’ own online operations.

Several hashtags branding protesters as “traitors” have made the rounds in recent days.

The social media influence war is part of religious parties’ efforts to regain influence online after they were sidelined by protesters. The loss of influence threatens the rule of the turbanis or Shia clerics, who have long used social media sites to promote myths of “sanctities” and “resistance.”

The project, revealed in an official letter sent by Sadr’s private office, is documented proof of his official support for an “electronic army.”

Most prominent Iraqi political and religious figures deny any association with bloggers accused of leading online campaigns against their opponents.

Rifts on social media often reflect Iraq’s sectarian divide.

“The majority of social media users are young people and adolescents who were born after 2003 or a few years before it,” said Irada al-Jubouri, assistant dean of the College of Mass Communication at Baghdad University.”

“Politicians contribute to inflaming emotions to create negative judgments, taking advantage of ignorance,” she said.

“The idea to create a permanent enemy existed for decades to distract citizens from basic issues such as providing security and services and curbing corruption,” she added.

In the past, Iraqis engaged in a large-scale electronic battle against “agents of Iran” in Iraq, especially clerics, whose criticism was a taboo. Many Iraqi Twitter users believe their country has been ruled by thieves and charlatans since 2003 and claim that the only path to recovery is getting rid of Iran’s agents.

Activists’ recent bold rhetoric seems to have annoyed Sadr and his clique. In a televised interview earlier this year, Sadr said protesters had “deviated from the right path and needed an ear-tip,” which many considered a veiled admission of responsibility for violence and killings against demonstrators.

Sadr, whose public statements often draw criticism, rarely appears in popular gatherings or in the media. When he is featured on television programmes, he asks for the interview to be recorded in advance, because, as he put it, he “sifts through speech.”

Sadr resides in the Iranian city of Qom, and is viewed by Iraqis’ as the embodiment of Iranian influence in their country.

The Twitter account linked to him is a striking example of this, with its content derided by activists as exploiting religion and resistance for political gains.

Activists say the turbaned cleric’s tweets no longer fool Iraqis who now largely view him as an “Iranian pawn.”

People familiar with Sadr say he is “of a simple mentality and a limited thinking,” as the man did not complete his education and did not even pass the elementary school stage.

“He cannot formulate an understandable sentence,” one source said on condition of anonymity.

No comments:

Post a Comment