President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin discussed the New START treaty in Helsinki, Finland, on July 16, 2018.

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

Alex WardAugust 3, 2020 6:00 am

In December 2019, a secretive group of elite Americans and Russians gathered around a large square table. It was chilly outside, as Dayton, Ohio, can get in the winter, but the mood inside was just as frosty.

The 147th meeting of the Dartmouth Conference, a biannual gathering of citizens from both nations to improve ties between Washington and Moscow, had convened. Former ambassadors and military generals, journalists, business leaders, and other experts came together to discuss the core challenges to the two countries’ delicate relationship, as members had since 1960.

In recent years, that has included everything from election interference to the war in Ukraine. But now the prospect of an old danger worried them most, just as it had the group’s quiet supporters President Dwight Eisenhower and Soviet Chairman Nikita Khrushchev decades before: nuclear catastrophe.

Proceedings typically start with a lengthy summary of the relationship, touching on security, medical, societal, political, and religious issues up for discussion. This time, the synopsis was unnervingly short.

“We went right into the nuclear issue,” said a conference member, speaking on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak openly about the event. “There was a belief we were in serious danger because it’s the end of arms control as we know it.”

“It was dramatic and sobering,” the member added.

The US and Russia were then barely over a year away from losing the last major arms control agreement between them: New START, short for the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. That agreement limits the size of the two countries’ nuclear arsenals, which together account for 93 percent of all nuclear warheads on earth. The deal expires on February 5, 2021, and those sitting around the table feared its demise.

The trepidation inspired the group’s four co-chairs to do something the Dartmouth Conference hadn’t done in its 60-year existence: release a statement.

Today, roughly half a year before New START stops, the group’s members continue to stress the consequences. “We’re at a decisive point,” said retired US Army Brig. Gen. Peter Zwack, who was at the December meetings. “The entire arms control regime of the past 50 years is about to pass.”

Seventy-five years ago this week, the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, unleashing a weapon of mass destruction on the world. Decades of painstaking diplomacy between the world’s two greatest nuclear powers, the US and Russia, helped keep both nations from unleashing that destructive power on each other ever since. But now the US and Russia are mere months from throwing it all away.

New START may soon join other defunct arms control agreements, including one prohibiting ground-based intermediate-range missiles scrapped in 2019 and another allowing overflights of nuclear facilities likely to end this year.

One reason for all of this: President Donald Trump wants to put his own stamp on arms control history, one way or another.

“They would like to do something, and so would I,” Trump told Axios about a July call he had with Russian President Vladimir Putin. “If we can do something with Russia in terms of nuclear proliferation, which is a very big problem — bigger problem than global warming, a much bigger problem than global warming in terms of the real world — that would be a great thing.”

“The president has directed us to think more broadly than the current arms control construct and pursue an agreement that reflects current geopolitical dynamics and includes both Russia and China,” a senior administration official told me on the condition of anonymity. “We’re continuing to evaluate whether New START can be used to achieve that objective.”

That evaluation has turned into a delicate process with Russia, with high-level and working-level meetings taking place in Vienna to see if New START can be salvaged. Officials from both countries met again at the end of July in Austria’s capital, while China — which the US wants involved to discuss limiting its nuclear and missile capabilities, even though it isn’t a party to New START — didn’t show up.

That may explain why Trump waffled on getting China involved. “We’re going to work this first and we’ll see,” he said outside the White House when asked about folding China into negotiations with Russia. “China right now is a much lesser nuclear power — you understand that — than Russia … we would want to talk to China eventually.”

Some say Trump has good reasons to rethink things. The Russians have cheated on previous deals. Washington could use Moscow’s clear desire to extend New START to its advantage, like getting them to promise no meddling in the 2020 election. And China, some believe, should be included in a modern set of agreements soon, if not now.

But even former Trump officials say those rationales shouldn’t mean the end of New START. “New START is working,” Andrea Thompson, the State Department’s top arms control official from April 2018 to October 2019, told me a few months after leaving the government. Former Vice President Joe Biden agrees, and has already vowed to seek an extension in the few weeks between the start of his presidency and the deal’s expiration.

Yet there’s still a chance Trump doesn’t continue the accord and Biden can’t strike a way forward.If New START ends, then, the general animosity between the US and Russia could lead to a nuclear arms race and prompt China to keep building up its forces — a situation unlike anything we’ve seen since the Cold War.

“We’re creating the greater threat of a conflict that could literally destroy each country and perhaps even our planet,” Leon Panetta, the former CIA director and defense secretary, told me.

The following account of the looming death of US-Russia arms control is based on conversations with over 20 current and former US officials, lawmakers, and experts on three continents. It traces the story of arms control from its origins to its possible end in the coming years, and what that end could mean for all of us.

The long and dangerous road to arms control

Washington and Moscow didn’t just sit down one day and decide, “Hey, we really should lower tensions and put restrictions on our nuclear arsenals.” They basically had to be scared and pressured into doing so.

It took decades of demonstrations, terrifying close calls, and nuclear surprises before both sides decided it was time to talk. Below are five of the most important moments on the path to arms control, briefly explained.

1) The rise of the anti-nuclear movement: After American forces dropped two atomic bombs on Japan in 1945, vividly demonstrating the horrifying power of those weapons, many Americans, and people around the world, rallied against them. The movement ebbed and flowed, but the overall result was that sustained pressure restrained US policymakers, Christopher Miller, an expert on US-Russian nuclear history at the Fletcher School at Tufts University, told me.

2) The US-Soviet standoff over Berlin: In 1958, Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier, wanted US, French, and British troops to leave West Berlin so the city could fall under Soviet-controlled East German authority. President Dwight Eisenhower left office without a resolution to the standoff. President John F. Kennedy escalated things, saying in a 1961 address: “We will at times be ready to talk, if talk will help. But we must also be ready to resist with force, if force is used upon us. Either alone would fail. Together, they can serve the cause of freedom and peace.”

In the end, a Kennedy-Khrushchev backchannel de-escalated the situation, but the Berlin crisis showed that any major disagreement between the two powers could eventually heighten and conceivably go nuclear. The implications were staggering.

3) The Cuban missile crisis: On October 14, 1962, the United States discovered the Soviets had put nuclear missiles in Cuba, just 90 miles off the southern tip of Florida. What followed was a 13-day crisis that brought America to the brink of war with the Soviet Union. It finally ended in a deal where each superpower would remove missiles from a single region: the Soviets from Cuba and the US from Turkey.

“I got introduced to the nuclear equation and dangers early on,” said Sam Nunn, who would go on to serve as a US senator from Georgia from 1972 to 1996, and to become a major figure in US nuclear policy, about his time as a congressional staffer on a trip to Germany during that period. “It was a very close call.”

4) China’s nuclear test: China tested its first nuclear device on October 16, 1964, becoming the fifth nuclear state (in addition to the US and USSR, Britain and France also had nuclear weapons by this point). China used technology given to it by the Soviets years before and caught the Americans mostly by surprise.

Both nations felt immense responsibility for letting the nuclear genie out of the bottle, experts say, in part because they had paved the way to getting the technology necessary to make the bomb. The US and Soviet Union thus worked to make arms control a reality.

5) Breakdown in Soviet-Chinese relations: The decline in Moscow’s relations with Beijing compelled the Soviets to build trust with America, despite much reluctance. After forming an alliance in the 1950s, ideological differences — namely the centrality of communism to domestic and foreign policy — led both capitals to drift apart from one another. Disagreement over a mutually claimed uninhabited island erupted in 1969, confirming the break.

But the split caused some heartburn in the Soviet Union, as leaders didn’t want spiraling relations with powers to its east and west at the same time. Moscow decided it could improve its ties with the US by curbing its nuclear arsenal.

In other words, it took an increasingly dangerous period before the US and the Soviet Union finally realized they had to build trust to avoid disaster. “There was a real strong feeling that this was an opportunity to try and contain what could happen,” Panetta, the former Pentagon and CIA chief, told me.

That feeling turned into action, and produced the first major arms control deals between the world’s most heavily armed nations.

“This is a turning point in the history of the world”

The first, most promising arms control talks between the Americans and Soviets formally began in November 1969, and after a little over two years of negotiations, the two countries signed a landmark nuclear arms treaty in Moscow.

The accord consisted of two agreements. The first was the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) of 1972, which restricted each country to just two anti-missile systems: one for the nation’s capital and another to protect an intercontinental ballistic missile field.

This was a big deal. Those systems were developed to shoot down incoming nuclear missiles: If the Soviets fired a ballistic missile at America, for example, the US could launch a missile of its own to destroy the Soviet one. Both countries considered putting these defenses throughout their lands to protect key places like major cities, military sites, and critical infrastructure.

But by only having two sites, the US and the Soviets basically agreed to leave most of their respective countries vulnerable to attack. Should the US fire a missile at most places in the Soviet Union, it would be almost certain to hit its target, but any retaliation by Moscow would likely strike its target in America, too. Keeping both sides relatively weak, then, was meant to prompt the countries to think twice before launching any missiles, and perhaps persuade them to stop developing more offensive capabilities.

The US Senate ratified the deal that August, and it went into effect two months later.

The other part of the pact, known as the Interim Agreement, capped US and Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) forces. The US couldn’t have more than 1,054 ICBM silos and 656 SLBM launch tubes. The Soviet Union was also unable to have more than 1,607 ICBM silos and 740 SLBM launch tubes.

Those two agreements, collectively known as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks — or SALT — kicked off the era of arms control between the two major nuclear powers.

This was a weighty moment in history: After decades of dangerously close calls and nuclear buildups, the world’s two strongest nations walked back from the edge and talked out their problems. The deal wasn’t perfect by any means, but it demonstrated the first sign of hope that maybe they wouldn’t blow up one another — and the world. Instead of racing toward destruction, they purposely curtailed their power for their own national interest and for the common good of the world.

“It is an enormously important agreement,” President Richard Nixon said in May 1972, speaking at a dinner before the signing ceremony, “but, again, it is only an indication of what can happen in the future as we work toward peace in the world. I have great hopes on that score.”

Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin concurred: The agreement would “go down in history as a major achievement on the road towards curbing the arms race,” he said. “This is a great victory for the Soviet and American peoples.”

Or, as one Soviet journalist covering the event put it: “This is a turning point in the history of the world.”

Arms control gained momentum …

The two countries were primed to keep working on restricting the strength and size of their arsenals. “The Americans and Soviets realized their stature would improve if they took arms control seriously,” Sarah Bidgood, an expert on Russia’s nuclear program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, told me. “They would look better in the eyes of the international community if they led on that issue.”

That momentum got a boost from several major events.

In 1974, India detonated its first nuclear bomb, which it developed using technology it received from American companies under an Eisenhower-era policy called “Atoms for Peace.”

“This visionary program was based on a bargain between the United States and developing states. The United States provided research reactors, fuel and scientific training to developing countries wanting civilian nuclear programs,” Ariana Rowberry, an expert in arms control and nuclear policy, wrote in 2013. “In exchange, recipient states committed to only use the technology and education for peaceful, civilian purposes.”

The program’s goal was to promote peaceful nuclear energy and scientific knowledge. But its lasting legacy is that it spurred the global spread of nuclear weapons. In fact, the policy helped build up the nuclear programs of Iran, Israel, and Pakistan, ultimately contributing to more nuclear proliferation, not less.

“[I]t is legitimate to ask whether Atoms for Peace accelerated proliferation by helping some nations achieve more advanced arsenals than would have otherwise been the case,” Leonard Weiss, a nuclear expert at Stanford University, wrote in 2003. “The jury has been in for some time on this question, and the answer is yes.”

Though both the US and the Soviet Union had been instrumental in driving it, this global proliferation of the deadliest weapons ever developed by humans ultimately deeply concerned Washington and Moscow. And it gave them that much more impetus to stop a widening nuclear spread.

The growth of anti-nuclear protests in the US also added to the push for further arms control. A major manifestation of this movement came in 1982, when 1 million people gathered in Manhattan on June 12 to protest nuclear weapons. “The groups participating ranged from radicals seeking immediate unilateral disarmament by the United States to moderates asking a resumption of negotiations on arms cutbacks,” the New York Times wrote the next day.

Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King Jr., spoke to that crowd during the rally. ‘’We have come here in numbers so large that the message must get through to the White House and Capitol Hill,’’ she said.

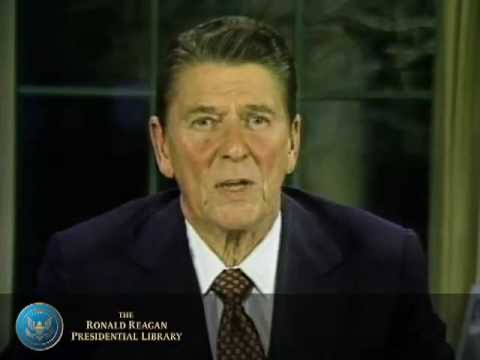

That movement inspired a similar one in Europe in the 1980s, when the Reagan administration wanted to put short- and medium-range missiles on the continent to deter the Soviet Union. The main fear was that Moscow might consider those actions so provocative that it would attack those positions and start World War III.

The protests proved so successful, the University of Hamburg’s arms control expert Ulrich Kühn told me, that in Germany, for example, they contributed to the resignation of Chancellor Helmut Schmidt.

During this tumultuous time, American and Soviet leaders met to strike more and more deals, or at least build on previous ones. Not every attempt succeeded, but the two nations would eventually sign more agreements over the next four decades, including an update to SALT — called SALT II, signed in 1979 — and the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

These agreements played a critical role in lowering tensions between the two nations and curbing the risk of nuclear escalation. Those tensions, though, were about to rise once again.

… and arms control teetered

President Reagan was worried the Americans and the Soviets would blow each other to smithereens. The reliance on “mutually assured destruction” — the notion that neither country would attack the other with nuclear weapons, because the retaliation would escalate into the annihilation of both countries — was folly to him. In fact, he called the concept a “suicide pact.”

His solution to the problem? “Star Wars.” No, not the film — a missile defense system involving lasers armed with nuclear warheads in space.

“What if free people could live secure in the knowledge that their security did not rest upon the threat of instant US retaliation to deter a Soviet attack, that we could intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies?” Reagan said in a national address in March 1983.

But the administration realized that creating such a system would contravene the ABM Treaty. After all, the whole point of the treaty was to ensure that each country could successfully attack the other with lots of nuclear missiles, thereby deterring either side from ever launching a strike.

If the US could now successfully use space lasers to intercept incoming Soviet missiles, that would put the US at a major advantage over the Soviet Union, thus upending the fragile balance of mutually assured destruction.

The “Star Wars” plan, formally known as the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), was ultimately scrapped, in part because of the ABM Treaty. Yet that the plan was seriously considered showed that the US commitment to arms control wasn’t so ironclad.

The real breaking point in the era of cooperation began in the early 2000s.

Months before becoming president, George W. Bush told a Washington crowd that he would reduce America’s nuclear arsenal to “the lowest possible number consistent with our national security.” But after the 9/11 attacks, Bush and his national security team concluded that the world had changed drastically. Old ways of thinking about national security needed an update, and that included arms control.

The Bush administration believed that arms control arrangements with the Soviet Union not only were anachronistic (after all, the Soviet Union didn’t even exist anymore by that point) but also limited America’s ability to defend itself.

Bush’s team cited two main reasons. First, the US needed all tools at its disposal to combat terror groups trying to harm America, and it didn’t want to be restricted if terrorists got a hold of a nuclear weapon. Second, concerns were mounting about Iran and North Korea improving their missile programs. Condoleezza Rice, then the national security adviser, thought the ABM Treaty limited America’s ability to respond if those countries were to launch an ICBM at the mainland.

As a result, Bush withdrew the US from the ABM Treaty, claiming it inappropriately restricted America’s might. “Defending the American people is my highest priority as commander in chief,” the president said in December 2001, “and I cannot and will not allow the United States to remain in a treaty that prevents us from developing effective defenses.”

Moscow saw this as the dawn of a more confrontational United States. “Russia perceived the US was now going full steam ahead in making its own international rules,” said Kühn, the arms control expert at the University of Hamburg. This perception only deepened as the US pushed for an expansion of NATO to include members nearer and nearer to Russia’s borders.

However, the Bush administration did sign the Strategic Offense Reductions Treaty (SORT, also known as the Moscow Treaty because of where it was signed) in May 2002. It committed the US and Russia to keep their deployed strategic nuclear forces between 1,700 and 2,200 warheads each for 10 years, and was ratified unanimously the following year.

The Bush administration decided to make the deal, some experts say, because it was basically costless. The accord was almost unverifiable, so the US could still be flexible if it needed to be, while Washington-Moscow ties improved at the same time.

President Barack Obama wanted to go further in the direction of arms control. During his first trip to Europe as president in 2009, he gave a speech in Prague vowing to reduce America’s number of nuclear weapons and announcing his intention to sign a new arms control deal with Russia.

As a way to garner support from Senate Republicans for a deal with Russia, Obama kick-started a nuclear modernization program that would cost billions and led to much criticism from arms control advocates. Some in line with Obama’s stated vision felt betrayed long after.

But the gambit worked: In 2010, he announced New START, which he called “the most comprehensive arms control agreement in nearly two decades.” The agreement, signed by Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev that April, reduced “by about a third — the nuclear weapons that the United States and Russia will deploy,” the White House explained at the time.

“It significantly reduces missiles and launchers. It puts in place a strong and effective verification regime. And it maintains the flexibility that we need to protect and advance our national security, and to guarantee our unwavering commitment to the security of our allies,” the White House statement continued.

The agreement went into effect on February 5, 2011, and replaced SORT. Under the terms of the treaty, the United States and Russia were to meet the limits imposed on their arsenals by February 5, 2018.

Nuclear war is a threat Donald Trump has often talked about over the years, and he has sometimes seemed genuinely concerned about it.

“I’ve always thought about the issue of nuclear war; it’s a very important element in my thought process. It’s the ultimate, the ultimate catastrophe, the biggest problem this world has, and nobody’s focusing on the nuts and bolts of it,” Trump said in a 1990 interview with Playboy.

Trump has said many times that he learned about the destructive power of nuclear weapons at an early age from his uncle John, a professor at MIT who was a renowned scientific mind. “He was a brilliant scientist,” Trump said in another Playboy interview, this time in 2004, “and he would tell me weapons are getting so powerful today that humanity is in tremendous trouble. This was 25 years ago, but he was right.”

When Trump took office on January 20, 2017, three major arms control-related agreements were in force: the INF Treaty, a confidence-building measure known as Open Skies, and New START, the agreement Obama had negotiated just a few years earlier.

Yet, rather than continue the progress his predecessors made toward making the world safer from the threat of nuclear war, Trump decided to tear it all down, while pursuing an exit from the Iran nuclear deal and ineffective nuclear diplomacy with North Korea.

Of those three US-Russia agreements, one is gone, another is almost gone, and the last, it seems, is on the way out. That’s not all bad, some experts say, as Russia did cheat on some of the agreements and the US showed those actions would have consequences.

But most experts I spoke to are concerned that Trump is tearing down an artifice with no new blueprints to make it better, or even rebuild what exists. “The whole arms control regime is under considerable stress,” former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz, who now leads the Nuclear Threat Initiative, told me. “It’s badly frayed.”

Let’s take each deal in turn.

The INF Treaty

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was signed by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in December 1987. It prohibited Washington and Moscow from fielding ground-launched cruise missiles that could fly between 310 and 3,400 miles.

Both countries signed the deal as a way to improve relations toward the end of the Cold War. However, the two nations still could — and since have — built up cruise missiles that can be fired from the air or sea.

Then a problem arose: Russia violated that agreement. In 2014, the Obama administration blamed the Kremlin for testing a cruise missile in direct violation of the accord. (Russia says the US had violated the agreement, too, by fielding ground-based missile defense systems that can fly within the prohibited ranges. The US, however, denies fielding the banned weapons.)

That led to months of hurried negotiations between Washington and Moscow to bring Russia into compliance again, but neither side caved. NATO, the US-led military alliance formed to thwart the Soviet threat, tried to increase pressure by stating in December that Russia violated the treaty’s terms.

The Kremlin didn’t budge during those talks. “We would confront them on it, and they would skirt responsibility,” said Thompson, who was responsible for leading INF negotiations in the Trump administration. “We knew we weren’t going to get anywhere. They weren’t going to be forthcoming about it, but we still kept chipping away.”

Ultimately, she said, “the president made the decision to leave” the deal. That officially happened in August 2019.

“Russia is solely responsible for the treaty’s demise,” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said at the time. “The United States will not remain party to a treaty that is deliberately violated by Russia.”

The wisdom of Trump’s choice depends on whom you ask. “Make no mistake, Russia caused this mess when they decided to develop, test, and deploy” the treaty-violating missile, said the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation’s Alexandra Bell, “but the Trump administration may have had more luck” than Obama did. “Now there is no clear plan about what to do next.”

Jeffrey Edmonds, who served as the National Security Council director for Russia in the Obama administration, told me he thinks Trump made the right call. “Nothing was going to bring the Russians back into compliance,” he said. “It kind of poisons the well when it came to arms control in general. If you are pro-arms control, you shouldn’t want to hold on to arms control agreements that don’t work, because it limits your ability to pursue other arms control agreements.”

With the INF treaty gone, some argue the US could now place ground-based intermediate-range missiles in Asia, mainly in Japan, to thwart China.

Most experts I spoke with said there’s little chance of that happening soon. “This is a theoretically interesting point,” said Mike Green, a Japan expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank in Washington, “but at this point, the Japanese ability to host US deep-strike weapons on Japanese soil is pretty low.”

However, three American experts who traveled to Tokyo to meet privately with local officials earlier this year said the issue often came up. Each time, though, there was this added twist: Japan might consider building and basing ground-based missiles of its own. That’s not something Japan is seriously pushing for right now, they noted, but it would fit with the island nation’s trend of beefing up its defenses.

At a minimum, those in favor of putting US missiles in Japan say it’s worth a shot. “I believe it is realistic, and I am hopeful that we will have an opportunity for basing these weapons in Japan,” Rebeccah Heinrichs, a nuclear expert at the Hudson Institute in Washington, told me. “But it’s going to take some work.”

Open Skies

Originally an idea by Eisenhower and made a reality in 2002, the Open Skies Treaty allows nations to conduct unarmed flights over another country’s military installations and other areas of concern. Entering into effect 10 years later, it has since helped the 34 North American and European signatories, including the US and Russia, gain confidence that others weren’t developing advanced weapons in secret or planning big attacks.

In other words, the treaty was put into place to prevent arms races — and wars.

In May 2020, Trump decided America would withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty, kicking off a six-month clock before the US could officially leave the deal.

“It has become abundantly clear that it is no longer in America’s interest to remain a party to the Treaty on Open Skies,” Pompeo said in a statement announcing the decision.

“At its core, the Treaty was designed to provide all signatories an increased level of transparency and mutual understanding and cooperation, regardless of their size,” he continued. “Russia’s implementation and violation of Open Skies, however, has undermined this central confidence-building function of the Treaty — and has, in fact, fueled distrust and threats to our national security — making continued US participation untenable.”

But that same day, Trump left the door open just a crack to nixing the withdrawal. “There’s a very good chance we’ll make a new agreement or do something to put that agreement back together,” he said outside the White House. “I think what’s going to happen is we’re going to pull out and they’re going to come back and want to make a deal.”

Still, the decision to leave was stunning, and arguably dangerous. The treaty allowed both Washington and Moscow to track each other’s movements. The imagery they collected was then shared among all the signatories, giving some less technologically advanced nations their only source of overhead intelligence.

That’s vitally important for, say, Ukraine, a treaty member that wants to know about Russian military movements on its border.

The worry was if the US left Open Skies, others would too. So far, that’s not the case. The Kremlin criticized America’s decision but hasn’t said if it will stay or leave. NATO allies signaled soon after Trump’s announcement that they would remain in Open Skies and other arms control pacts, and the foreign ministries of at least 10 European nations vowed to remain signatories.

That makes sense, since those countries would still benefit from the intelligence collection from overflights, even though they’re likely to lose a large number of images after America’s departure.

The US, then, has separated itself from multiple allies with the unilateral decision to withdraw from the treaty. But that won’t bother the president’s supporters who long cited three reasons he needed to take the US out of Open Skies.

First, as Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) articulated in 2019, the US could spend its money elsewhere. After all, the US has many spy satellites in space, so the utility of spending money to fly creaking planes for days over Russian and other territory doesn’t make much sense, the treaty’s critics say.

Second, many said Russia was a cheating treaty member.

As Defense Secretary Mark Esper told reporters in February, the Russians aren’t playing by the rules. “The Russians have been noncompliant in the treaty for years, specifically when it comes to their allowance of overflights and near flights [of] Kaliningrad and Georgia,” he said.

It was a fair point. Russia did restrict US overflights of Kaliningrad — the Russian exclave in Europe’s northeast — to 310 miles in the territory and within a six-mile corridor of its border with Georgian conflict zones Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Meanwhile, the US rarely, if ever, impeded Russia from at least attempting to see what it wanted to.

“Yes, the Russians are violating that treaty, too, by restricting flights,” Thompson, Trump’s former top arms control diplomat, told me. “The treaty does provide transparency but my sense is it’s largely a symbolic treaty — it helps the alliance — as it provides intelligence for our allies that don’t have the capabilities we do.”

The impediment of flights, though, wasn’t much of a concern for former Secretary of Defense James Mattis. He told Sen. Deb Fischer (R-NE) in a May 2018 letter that “it is in our Nation’s best interest to remain a party to the Open Skies Treaty” after she complained about Russia’s cheating.

Many experts side with the then-Pentagon chief’s stance. “These issues do not rise to the level of a material breach, nor do they justify withdrawal,” Kingston Reif, an expert at the Arms Control Association, told me in October 2019.

Third, some experts claimed the deal helped Russia much more than it served America.

In 2016, then-Defense Intelligence Agency Director Gen. Vincent Stewart told the House Armed Services Committee he was worried about what Russia could learn due to the treaty.

“The things that you can see, the amount of data you can collect, the things you can do with post-processing, allows Russia, in my opinion, to get incredible foundational intelligence on critical infrastructure, bases, ports, all of our facilities,” he said. “So from my perspective, it gives them a significant advantage.” He later added that he’d “love to deny” Russia overflights.

That’s all fair, especially if Russia was getting better quality information than the US. But advocates of the treaty note that what Moscow learned was outweighed by what the US obtained and shared with its allies in the accord, particularly Ukraine. “The treaty has been of particular value recently in countering Russian disinformation and aggression against Ukraine,” Reif said.

Yet the US dropped Open Skies, just as it soon might with New START.

New START

As a reminder, the New START arms control deal became effective in 2011 during the Obama administration. The treaty’s goal, essentially, is to limit the size of the American and Russian nuclear arsenals, the two largest in the world.

To ensure those limits are met and kept, the treaty also allows Washington and Moscow to keep tabs on the other’s nuclear programs through stringent inspections and data sharing, thereby curbing mistrust about each other’s nuclear and military plans.

At the time, it was heralded as a major achievement and is still considered such by top lawmakers.

“I stood behind President Obama in the Oval Office when he signed the New START agreement nine years ago. This landmark treaty has reduced the threat posed by nuclear weapons around the world,” Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), a member of the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees, told me. “I’ll continue to urge the Trump administration to extend the New START treaty so we can keep safeguards in place that oversee Russia’s nuclear arsenal and ensure every measure is taken to shore up our national security.”

As of mid-July 2020, the two nations had exchanged more than 20,400 total notifications about the state of their arsenals.

Rose Gottemoeller, who led the New START negotiations for the US at the State Department, told me all that goes away if Trump decides not to stay in the agreement. “The Russians won’t allow for verifications and inspections without a legal basis,” she said. And without the ability to get deep insight into Russia’s nuclear forces, trust would surely erode.

“The exact thing which gives us an excellent understanding of Russian strategic forces is all going to break down,” said Gottemoeller, who in 2019 stepped down as NATO’s deputy secretary. “Unless you have access to verify what’s going on with the warheads on missiles or submarines, you don’t really understand what’s going on.”

Putin, Russia’s president, says he sees value in the deal. “Russia is not interested in starting an arms race and deploying missiles where they are not present now,” he told Russian officials in December. “Russia is ready to immediately, as soon as possible, by the end of this year, without any preconditions, extend the START Treaty so that there would be no further double or triple interpretation of our position.”

Trump hasn’t taken up Putin on his offer yet, even though those two could extend the agreement for up to five years without anyone else’s input.

“ If Washington is fretting the end of arms control, it sure isn’t acting like it — and neither is Moscow ”

So why get out of a deal that almost everyone says is vital to keeping US-Russia relations stable? The answer is China.

“We need to make sure that we’ve got all of the parties that are relevant as a component of this as well,” Pompeo told reporters in 2019, clearly alluding to China. ”It may be that we can’t get there. It may be that we just end up working with the Russians on this. But if we’re talking about a nuclear [capability] that presents risks to the United States, it’s very different today in the world.”

It’s a legitimate concern. Beijing has spent the past few years building up its missile arsenal. It has short-, intermediate-, and long-range missiles capable of making any military, including America’s, think twice about attacking it. And while it only has about 300 warheads, far fewer than the US and Russia, it has enough bombs and missiles to carry them to retaliate. If the US wants to drop a nuke on China, China can drop a nuke on the US right back.

That’s a big change from when the US and Russia signed New START almost a decade ago. Many in the Trump administration and outside experts argue it’s worth using the treaty’s imminent demise to pressure Moscow to either stop harming the US, such as with election interference, or get Beijing to join a broader arms control agreement.

In July, top US arms control negotiator Marshall Billingslea extended an “open invitation” to Chinese officials to join the US and Russia in Austria for New START talks, even though Beijing has long said it won’t sign on to New START since its arsenal is so much smaller than Washington’s and Moscow’s.

The Chinese government didn’t accept the offer, leading Billingslea to take a swipe at the country on Twitter.

That wasn’t taken well by Russia and China. The Russians asked for the flags to be taken down ahead of the meeting, and the top arms control official in China’s foreign ministry blasted Billingslea in response to the tweet.

It was a microcosm of the jam the US put itself in: New START — the last major arms control deal between the US and Russia — may expire if China doesn’t join in. It’s a deeply misguided stance, experts say.

“They [the Chinese government] don’t trust arms control,” Tong Zhao, a Beijing-based expert on China’s nuclear program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told me. “They don’t see it as a way to defend Chinese security interests. They view arms control as a way to control others’ military power, so they want to delay Chinese arms control as much as possible.”

“That mainstream view in China is entrenched and cynical,” Zhao continued. “It’ll take decades to change.”

That’s why nuclear experts like Nunn, the former US senator from Georgia, argues the US should at most try to get Beijing to make an anti-nuclear statement along with Washington and Moscow, but not try to get them to sign a new pact before February. “But in the long run,” Nunn made sure to say, “China needs to be involved” in an arms control agreement with the Americans and Russians.

Others are skeptical of the Trump administration’s intentions. While there is merit in discussing arms control with the Chinese — especially on issues of nuclear weapons, hypersonics, and cybersecurity — they say pushing for those talks on such a tight timeline is nothing short of a ruse to kill New START.

“It’s a phantom endeavor, an obvious ploy,” Taylor Fravel, an expert on China’s military strategy at MIT, told me. “Why would China join an agreement with much bigger arsenals than theirs?”

“It’s just not going to be easy for China to go along with strategic stability discussions,” he added.

Everyone I spoke to, though, noted Trump’s hard line on arms control with Russia and China is consistent with this administration’s nuclear approach. If Washington is fretting the end of arms control, it sure isn’t acting like it, and neither is Moscow.

The new arms race

“Arms control creates an additional layer of insurance between states not getting along well and a possible hot war,” Samuel Charap, who served as a senior adviser to Gottemoeller after New START entered into force, told me. “If you remove the failsafe, you create more risk.”

Without the longstanding architecture in place, Washington and Moscow would enter a dangerous arms control hiatus and could see already poor relations spiral out of control.The US and Russia have many nuclear-tipped missiles already pointed at each other, but it would be even worse if both sides try to one-up their adversary by creating more deadly and usable weapons.

That, unfortunately, is exactly what’s happening. Welcome to the new arms race.

Take the American side of this first: The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, released in February 2018, lowered the threshold for dropping a bomb on an enemy.

Basically, the US said it would launch low-yield nuclear weapons — smaller, less deadly bombs — in response to non-nuclear strikes, such as a major cyberattack. That was in contrast with previous US administrations, which said they would respond with a nuke only in the event of the most egregious threats against the US, like the possible use of a biological weapon.

The document also calls for more, smaller weapons on submarines and other platforms to attack enemies. Many experts worry that having smaller nukes makes them more usable, thereby increasing the chance of a skirmish turning into a full-blown nuclear war. (Think, for example, of the US-China trade war escalating to the point that Trump thinks his only option is to launch a smaller nuke, or how Trump could respond to Beijing after a devastating cyberattack on US infrastructure.)

The US has already put its new nuclear strategy into overdrive. America’s armed forces placed their first low-yield nuclear weapon on a submarine in February, which means Washington now has a stealthy and hard-to-defend-against way to deliver a nuke to almost any point on earth.

If you’re in Moscow or Beijing, this may all be alarming news. In the US, the wisdom of these decisions depends on whom you ask.

Thomas Countryman, the assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation from 2011 to 2017, thinks the move ratchets up the chance for nuclear war.

“It would be practically impossible to prevent a limited use of nuclear weapons from escalating into an all-out strategic exchange of weapons,” he said, implying bigger nukes would soon follow the smaller ones. “The willingness to contemplate such use makes it more likely that [a strike with a low-yield nuclear weapon] will occur at some point.”

Matthew Kroenig, a nuclear expert at the Atlantic Council think tank, has a different take. He told me in 2018 that having smaller tactical weapons is a good idea. Our current arsenal, which prioritizes older and bigger nukes, leads adversaries to think we would never use it. Having smaller bombs that America might deploy, then, makes the chance of a nuclear conflict less likely. “It gives us more options to threaten that limited response,” Kroenig told me. “We raise the bar with these lower-yield weapons.”

But the US isn’t just experimenting with low-yield bombs. The Trump administration’s plans include spending more taxpayer dollars on nuclear development, including another new submarine-launched bomb. There are also new funds to develop conventional intermediate-range missiles, the same ones the INF Treaty prohibited.

In March 2018, Putin gave a dramatic speech to his nation in which he boasted about creating new, unstoppable weapons.

He said Russia was working on a cruise missile, powered by nuclear technology, that could reach the United States; nuclear weapons that could evade any missile defense system; and unfindable drone submarines that could be used to blow up foreign ports.

Experts at the time told me the most impressive new weapon Putin revealed was the nuclear-powered cruise missile he claimed could hit any point on the planet. (That’s big: Conventional cruise missiles rarely travel more than 600 miles.) This kind of weapon moves so quickly and flies so low to the ground that it could evade US and European missile defense systems and hit intended targets with a nuclear weapon.

Putin said the new technology would render American missile defense “useless,” but US officials say it needs further testing and is not yet operational. In fact, a radioactive explosion in 2019 in Russia may have been caused by a failed test of this very weapon.

But Moscow has succeeded in another area: hypersonic weapons. In December, the Russian military said it deployed one for the first time, a claim American officials don’t particularly doubt. It’s a provocative move, as this kind of missile could carry a warhead at about 3,800 miles per hour, fast enough to make it near-impossible for any defense system to stop it.

It looks like the Russians beat the Americans to the hypersonic punch. The US doesn’t plan to have a similar projectile in its arsenal until 2022 at the earliest, though that timeline is optimistic for many.

Despite all this, experts I spoke to said Moscow doesn’t really want an arms race. The Soviets already lost one to the US during the Cold War. Now that Russia has big economic problems, it could ill afford to engage in a long-term spending spree on weaponry.

“If there’s any country least ready for an arms race right now, it’s Russia,” Miller, the expert on Russian history at the Fletcher School, told me. “Even if they started the race a couple years ahead by violating the INF Treaty, that doesn’t give me or many people the confidence they’ll end the race ahead in 20 or 30 years.”

This would explain why Putin wants to extend New START so badly, and why the US believes it could use that desire as leverage. What’s certain is that the administration argues it’s no longer the time for old-school arms control ideas, as a top State Department arms control official, Christopher Ford, made clear in a February speech.

“I want to replace them with a discourse much more likely to be relevant to current conditions, more likely to improve real-world outcomes, and much less desperately maladaptive in the contemporary geopolitical environment of great power competition,” he told a London audience. “It should be increasingly clear that this arms control pathology is a completely inappropriate and even dangerous answer to the problems of international peace and security in today’s complex and challenging world, and we’re not shy about pointing this out.”

But at this rate, what he and Trump may get instead is no arms control at all.

“You’re pouring gasoline onto a fire”

If you’re starting to fear that a nuclear war is coming, the good news is the chance of one remains very low. The US and Russia have every incentive to avoid such a disaster, and they have done so thus far, in even the tensest moments.

But it’s fair to say many are worried about the long-term implications of current tensions. “You’re pouring gasoline onto a fire, and accelerating all of these trends to arms racing and proliferation globally,” says Nicholas Miller, a nuclear expert at Dartmouth College. “It could be quite dangerous.”

Three main consequences of the imminent death of arms control as we know it are broadly expected.

First, the US may lose global legitimacy as a leader in stopping nuclear proliferation. This year is the 50th anniversary of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), an international agreement to stem the spread of nuclear weapons around the world. None of the largest nuclear weapons states have signed on to it, but that’s because of an implicit understanding.

“The NPT is supposed to be a bargain between those that don’t have nuclear weapons and those that do,” said Middlebury’s Bidgood. “Non-nuclear weapons states expect those that have them to disarm, and if they don’t, then non-nuclear nations might leave the treaty because why would they limit their own capability?”

A review conference for the treaty was supposed to take place in April but was postponed due to the coronavirus. Whenever it meets, the lack of US-Russia arms control commitment could make it the testiest gathering in decades. Some may seriously push for the NPT to be dissolved. And if that’s the case, what’s to stop nations like Iran, Saudi Arabia, or others from sprinting toward the bomb?

Second, the end of an important era in global security fades away with nothing to replace or build on it. “The good old days when arms control was going hand-in-hand with a cooperative security relationship — which basically ties my security to your security — those days are gone, and I don’t see them coming back,” said the University of Hamburg’s Kühn. The only chance of a return to that time, he added, would likely be after Trump, Putin, and Chinese President Xi Jinping leave their offices.

But by then, it’s possible the arms control muscle may have atrophied.

Third, yes, the risk of a nuclear exchange between the world’s foremost powers will go up. Few I spoke to, though, argued that possibility would grow immediately.

Gottemoeller told me she thinks Washington and Moscow would show some goodwill toward each other in the short term. But over time, tensions would surely rise as they lose insight into what the other is planning.

“Each side will accuse the other of breaking out” of New START’s restrictions and may revert to banned practices, like putting nets over silos to keep them from satellite observation. “I can see a period of mutual recrimination and possibly a build-up of strategic forces,” but perhaps not missile forces because of their immense cost, Gottemoeller continued.

That’s why experts like Nunn want the US and Russia to take new negotiations seriously. “If you have over 90 percent of the weapons that can destroy God’s universe, you have a responsibility to talk,” he told me.

There are reasons for optimism.

Washington and Moscow are having conversations now, including a working-level meeting in July in Vienna. Even though the administration is skeptical of arms control, and Billingslea is not a fan of the concept, Trump’s team at least hasn’t outright rejected negotiations.

However unlikely now, the two powers could come to an agreement before New START’s expiration on February 5. If they don’t, a newly elected Joe Biden could quickly reach a deal with Putin before the deadline, though he’d have limited time since his term would start in late January. “The election in November will be a major inflection point for New START specifically,” Moniz, the former energy secretary who helped strike the Iran nuclear deal, told me. “If Biden wins, I can’t imagine that he wouldn’t extend New START.”

And perhaps the future of arms control will feature more executive agreements, like the Iran deal, and fewer treaties, in large part due to the rancorous politics in Washington. That would mean the power to make nuclear pacts would shift in an even greater direction to a president.

This moment could be just a blip in an otherwise positive, decades-long story of how two enemies found a way to pull back from the brink.

But when I asked experts if they felt arms control may soon be a thing of the past, the nearly unanimous sentiment was resigned acceptance. “My heart says no, but my head says yes,” Charap, who’s now at the RAND Corporation, told me after a long sigh. “The arms control era doesn’t have to come to an end, but it seems like it is.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

No comments:

Post a Comment