Reports

by David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Frank Pabian

August 28, 2020

The Abadeh site, which Iran razed in July 2019, is the Amad Plan’s Marivan site, an important test site responsible for conducting large-scale high explosive tests for developing nuclear weapons. This report provides an introduction to the Marivan location and its activities based on information in the Nuclear Archive, a significant portion of which was seized by Israel in 2018 and shared widely. A Farsi-language slide set from the archive obtained recently by the Institute, containing ground photos of a large-scale test, enabled the Institute to independently evaluate, geo-locate, and, in light of other Archive reporting, ultimately confirm the Abadeh site as Marivan.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has raised concerns about the existence of “Marivan” starting before 2011, but did not know the location of the site at that time. More recently, after learning of the location of the site in the Nuclear Archive, and discovering more of the high explosive tests done at the site, in 2019 and 2020, the IAEA repeatedly asked Iran to visit this site, as a location involved with undeclared nuclear material and activities. 1 On a recent trip to Iran, the IAEA’s Director General obtained an Iranian commitment to allow the inspectors access to this site (identified by Iran as near Shahreza, which is just north of Abadeh) as well as another one engaged in the past with undeclared nuclear material and activities (reportedly near Tehran). 2,3 Although a welcome commitment, Iran granting access is just the beginning. It remains unclear if these visits will resolve the outstanding questions that the IAEA has related to safeguards in Iran and, in particular, to the broader issue of access to military sites and Iran’s lack of a complete safeguards declaration. Lack of full cooperation in allowing access to the sites, failure to answer the IAEA’s questions, and inhibiting the taking of environmental samples should lead the Board of Governors to refer the issue to the UN Security Council for further action. Member states and the IAEA should also use overhead imagery to scrutinize the sites, particularly the Marivan site, to ensure that Iran does not carry out additional sanitization activities that could interfere in the inspections and sampling. Finally, it is once again worth noting the usefulness and importance of the Nuclear Archive in identifying Iran’s undeclared nuclear sites, materials, and activities. Acceptance of the IAEA visits reveals Iran’s increasing inability to deny the authenticity and legitimacy of the information in the Nuclear Archive.

Introduction

The Amad Plan, Iran’s crash nuclear weapons program in the early 2000s, conducted its larger high explosive tests related to the development of nuclear weapons at the Marivan site. The site’s location, long unknown to Western intelligence, the IAEA, and the public, is a mountainous region of central Iran, about 24 kilometers north of the town of Abadeh. Information in the archive shows that the Marivan site undertook work linked to implosion testing for nuclear weapons.

The IAEA discussed this site in a June 2020 report alleging Iran’s undeclared nuclear material and activities, describing this site as one “where outdoor, conventional explosive testing may have taken place in 2003, including in relation to testing of shielding in preparation for the use of neutron detectors.” 4 The IAEA also emphasized that this site had been razed in July 2019. After the Amad Plan and up until the razing, the site had changed little, suggesting that Iran may have continued to use the site or intended to reactivate it at some point up until its discovery by Israel, which, as was likely also expected, resulted in a subsequent IAEA enquiry. That Abadeh remained intact for so long also facilitated the use of post-2003 satellite imagery to evaluate the site.

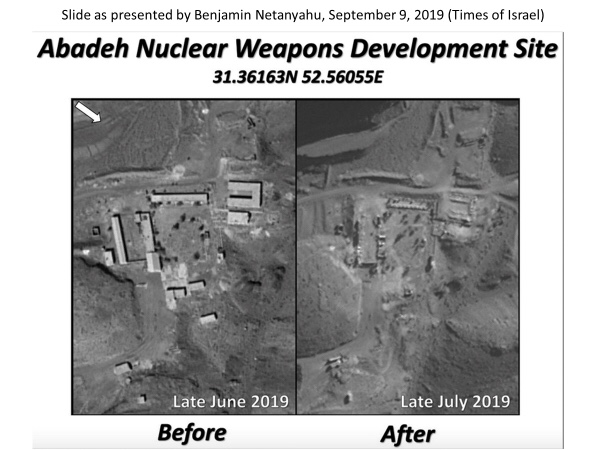

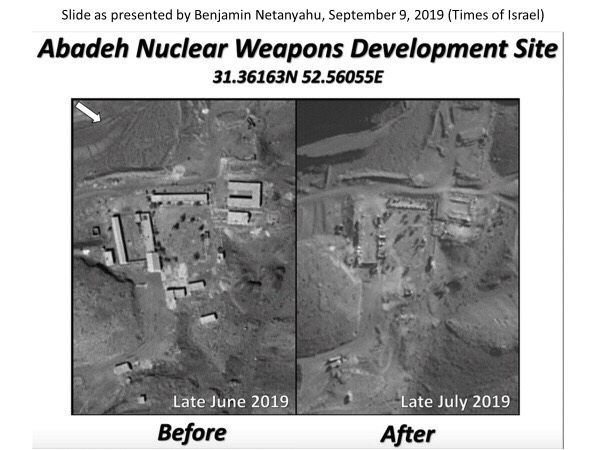

The location of the Marivan site was first made public on September 9, 2019 by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who revealed at a press conference the existence of this previously clandestine nuclear weapons development site. However, he did not at the time identify it as the Marivan site, but merely as a site connected to the Amad Plan engaged in conducting “experiments to develop nuclear weapons.”5 The Prime Minister went on to say that once Iran became aware of Israel becoming witting to the existence of the site, the Iranians quickly destroyed the entire site in July 2019. Figure 1 is taken directly from the Prime Minister’s presentation, showing the site before and after its razing.

Figure 1. Prime Minister Netanyahu used these before and after pictures of Abadeh to show the site’s abrupt razing in July 2019.

Nuclear Archive

The Nuclear Archive contains extensive information about the Marivan site. The information includes ground photographs and descriptions and results of nuclear weapons-related testing. In particular, the archive shows that the Amad Plan’s nuclear weaponization effort, Project 110, used the Marivan site to conduct tests of large scale hemispherical multi-point initiation (MPI) systems, including one such test in 2003 known to the IAEA. The archive also indicates that the site was used for several such experiments, and can now be identified as one of four sites previously engaged in nuclear weapons component testing. 6 During one two-month period, between February 20 and April 20, 2003, based on an Iranian document from the archive, four tests under Project 110 were conducted at Marivan. 7 There could have been other large-scale Project 110 tests at the site after this time period.

The archive information also suggests that Marivan was the designated Amad location for conducting a cold test, the testing of the assembled nuclear explosive device without weapon-grade uranium. This critical test could determine that the nuclear explosive device would work when outfitted with nuclear explosive material and a neutron initiator, typically the last test before building the nuclear weapons. This type of test is also suggested by the IAEA reference to the explosive testing of shielding for neutron detectors, equipment critical to determine the success of the firing of the cold device, in particular detecting neutrons from the neutron initiator. Although a cold test avoids the use of nuclear explosive material, it would still likely involve the presence of nuclear material, namely natural uranium in shielding or as a surrogate material for the weapon-grade uranium.

The Institute recently obtained parts of a Farsi-language slide set from the archive about a Marivan test, possibly the large-scale 2003 test mentioned above or a similar one, containing ground photographs. The information confirms the test site as part of the Abadeh location and demonstrates its use for implosion testing. This slide set is discussed and analyzed in a later section of the report.

Overview of Marivan

Figure 2, an October 2015 Google Earth image, provides a perspective view of the overall Marivan site at Abadeh. The figure shows the general layout of the site: a cluster of key buildings hidden behind a hill from view from the main access road, with a security checkpoint at the entrance. The Abadeh development site was evidently established to conduct outdoor experiments involving greater amounts of high explosives than was possible in the indoor explosive chambers at Parchin and Sanjarian. 8 Newly acquired ground images now indicate that at least one high explosive experiment was conducted northeast near a hillside, further away from the main building cluster. Another area that the Institute had originally judged to have been suitable as an outdoor testing location for tests involving larger amounts of high explosives and optical diagnostic equipment is located in the north-northwest of the Marivan site. 9

Figure 2. The layout of the identified Marivan site at Abadeh before razing was consistent with ground photos and the reporting of secret high explosives testing for nuclear weapons development. Based on correlations with the available ground photos from the Nuclear Archive, the likely area of at least one circa 2003 outdoor high explosives test is in the northeast at the base of a steeply sloped hillside.

2003 MPI Test at Marivan

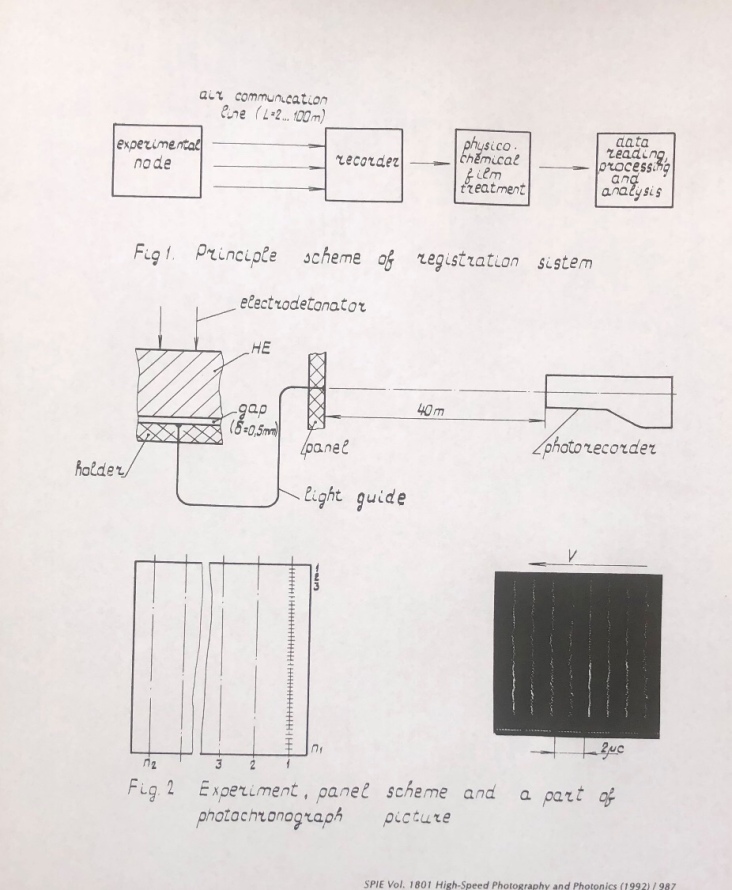

Prior to the seizure of the Nuclear Archive, information became public about a large-scale hemispherical MPI test in 2003 at Marivan. 10 And even before that, prior to 2011, a member state had shared information with the IAEA that describes this experimental setup, which aimed to measure the time of arrival of the detonation front, 50 kilograms of Composition B explosives in the form of a shell placed inside a hemispherical shock generator system. (The shock wave generator is a multi-point initiation system, which has the purpose of uniformly initiating a spherical shell of high explosives, or the “main charge,” which in turn compresses the nuclear core made from weapon-grade uranium to achieve a supercritical mass for a nuclear explosion. 11) The time of arrival of the detonation front at the outer surface of this 50 kilograms shell of explosives was measured by using many hundreds of fiber optic cables drilled into a thin hemispherical shell or holder in close proximity of the inner surface of the explosives. The other end of each of the cables was attached to a panel. The light signals were then transmitted via air to a fast-acting camera with a rotating mirror, likely a framing camera, at a safe distance from the explosion. On firing, the exploding bridgewires ignited the PETN explosives in the channels of the shell, setting off the explosive pellets in the holes in the shell (shock wave generator), in turn initiating the outer surface of the Composition B shell. The detonation front traveled through the main charge and on exiting the inner surface produced light, which was transmitted via the fiber optic cables and was captured on the film of the high-speed camera.

This description with less detail is in the 2011 IAEA report:

Information provided to the Agency by the same Member State referred to in the previous paragraph [not included here] describes the multipoint initiation concept referred to above as being used by Iran in at least one large scale experiment in 2003 to initiate a high explosive charge in the form of a hemispherical shell. According to that information, during that experiment, the internal hemispherical curved surface of the high explosive charge was monitored using a large number of optical fibre cables, and the light output of the explosive upon detonation was recorded with a high speed streak camera. It should be noted that the dimensions of the initiation system and the explosives used with it were consistent with the dimensions for the new payload which, according to the alleged studies documentation, were given to the engineers who were studying how to integrate the new payload into the chamber of the Shahab 3 missile re-entry vehicle (Project 111). 12

There is one publicly available picture from the archive that apparently shows a model of this experimental system using optical fibers (Figure 3). This model shows a hemispherical object representing the external side of the multi-point initiation system, where inside would be the high explosives and an inner surface, or holder, where the fiber optic cables would connect. The fiber optic cables exiting the hemisphere and the panel can also be seen. (The archive contains many images of actual hemispherical configurations for this type of test as well as other hemispherical high explosive tests related to developing implosion-based nuclear weapons. However, those images, in addition to a considerable amount of other information, were judged as nuclear weapons-sensitive and not made public by Israel.)

Figure 3. Model of an experimental system in the Nuclear Archive representing what appears to be a shock wave generator and high explosives, with a diagnostic system using fiber optic cables, to measure time of arrival of a detonation front in the main charge.

The IAEA also highlighted V.V. Danilenko’s involvement in this initiation system and diagnostic equipment in its 2011 report:

The Agency has strong indications that the development by Iran of the high explosives initiation system, and its development of the high speed diagnostic configuration used to monitor related experiments, were assisted by the work of a foreign expert who was not only knowledgeable in these technologies, but who, a Member State has informed the Agency, worked for much of his career with this technology in the nuclear weapon programme of the country of his origin. 13

The IAEA recognized that the diagnostic system used in this MPI test is similar to one Danilenko presented in two papers in the early 1990s at a conference on high-speed photography and photonics. In their papers, Danilenko and his colleagues from the Federal Nuclear Center, the All-Russian Institute of Technical Physics (VNIITF), presented an optical technique in which fiber optic cables are used to capture the time of arrival of an explosive shock wave on a fast camera. 14 VNIITF was created as a back-up facility for the All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Physics (VNIIEF) and contained expertise in the entire spectrum of work connected with the design and development of nuclear weapons.

Archive Document Supports Large-Scale MPI Test at Marivan

The Institute only very recently acquired some pre-and post-test ground images—part of a slide presentation obtained from the Iranian Nuclear Archive—reported to be of a nuclear weapons development related high explosives experiment at Marivan (Abadeh), circa 2003. This information has similarities to the large-scale MPI test discussed above. The test may have involved a large-scale MPI test that used the diagnostic technique developed by Danilenko and his colleagues, discussed above and in earlier Institute publications and represented in the hemispheric model shown in Figure 3. Figure 4, below, shows a schematic from one of Danilenlko et al’s papers that shows the basic structure of this system, illustrating it with one fiber optic cable labeled “light guide”. In actuality, there would be hundreds.

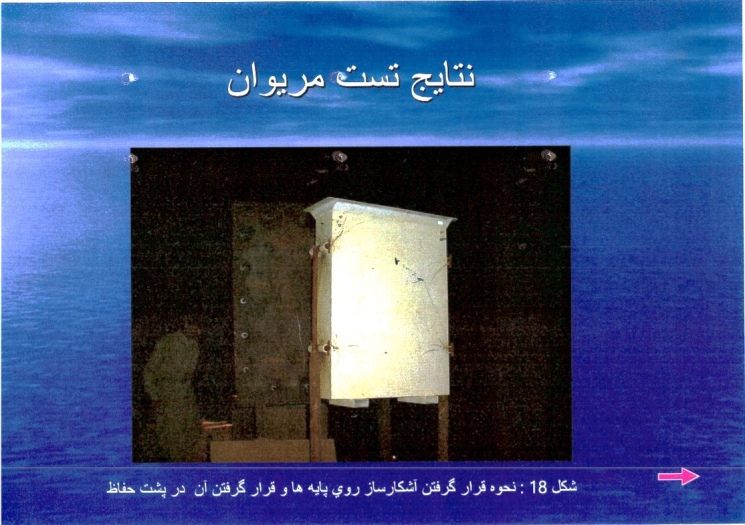

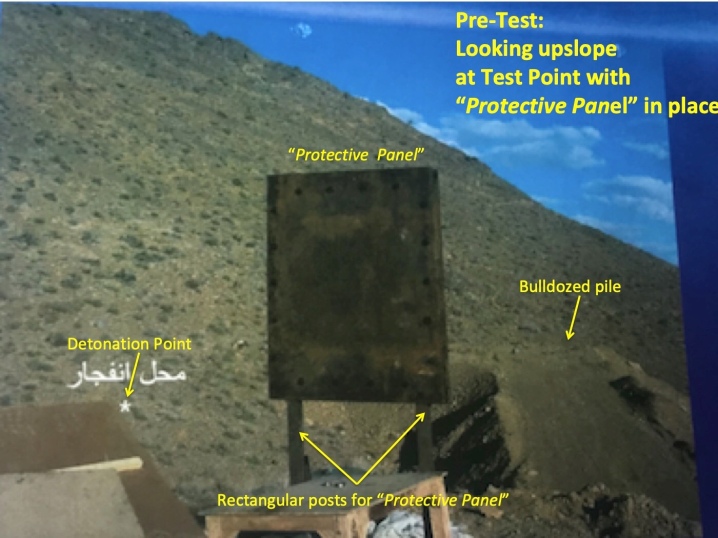

Figure 5 is a slide from the Archive slide presentation, the entirety of which is titled “Marivan Test Results.” The caption reads, “Figure 18, The positioning of the detector on its base and its placement behind the shield.” The photo in the center of the slide is a ground image showing a detector in shape of a white rectangular case, possibly containing the panel in the Figure 4 schematic that could be where the fiber optic cables end. The panel is situated in front of a metal sheet. Figure 6 shows the pre-test set-up of the metal sheet at the outdoor testing area, near what is labeled in Farsi as the “explosion point.” The photorecorder or fast camera is not shown in the available ground imagery, but could have been installed in a nearby structure identified in satellite imagery about 40 meters from the possible explosion location, which would also be consistent with the 40 meter distance specified in the Figure 4 schematic (see Figure 10).

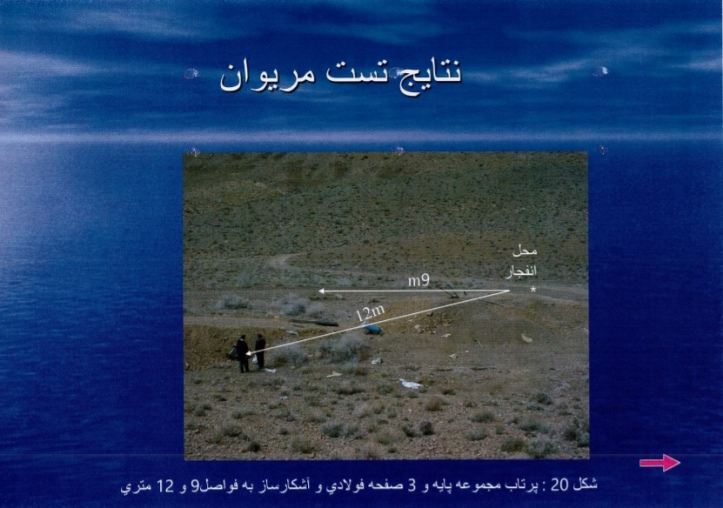

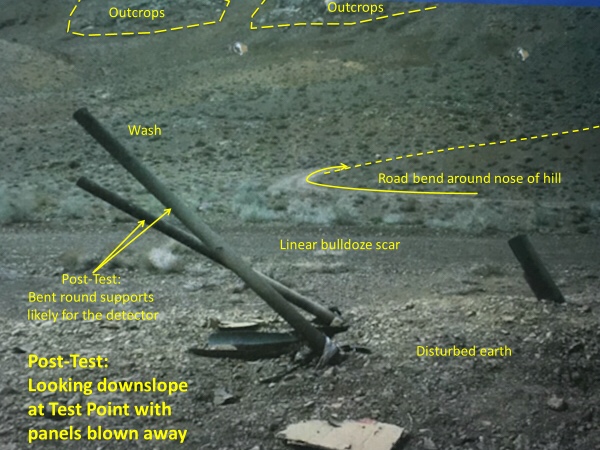

Further ground photos from the slide presentation show the aftermath of the explosion and the impact of the blast on some of the equipment, including on the metal (probably steel) shield, which is bent inwards after the explosion. Figure 7 is a slide showing remnants of the detector housing and other equipment blown as far as 9 meters in one direction, and 12 meters in another direction. Some of these additional ground images were used to geo-locate the testing area in Google Earth via terrain matching.

Figure 4. Schematics from Danilenko et al.’s report on a fast, fiber optic diagnostic system. “Electrodetonator” is another name for a shock wave generator. Note the lines on the photo from a raster system. As can be seen, the camera is placed at a safe distance of 40 meters from the explosion. Reprinted from: “Multichannel optical fiber system to measure time intervals in investigations of explosive phenomena,” see footnote 14.

Figure 5. The title repeats the title of the slide presentation, “Marivan Test Results.” The caption reads, “Figure 18, The positioning of the detector on its base and its placement behind the shield.” The slide is part of a slide set from the Iranian Nuclear Archive, translated by the Institute. The white case in the foreground could contain or correspond to the panel used as part of the detection and transmission of the light signals from an MPI test.

Figure 6. A close up of the photo in slide 17 of the Nuclear Archive slide set titled “Marivan Test Results.” The caption of the slide (not shown) reads “The location of the explosion and the positioning of the metal shield (protective panel) in front of it.” The white Farsi annotation in the photo labels the “explosion point”, marked by an asterisk. English translation and annotations by the Institute.

Figure 7. Slide 20 of the Nuclear Archive slide set titled “Marivan Test Results.” The caption reads, “The throwing of the set of the base and three steel plates and detector to the distances of 9 and 12 meters.”

Geo-locating the Testing Area

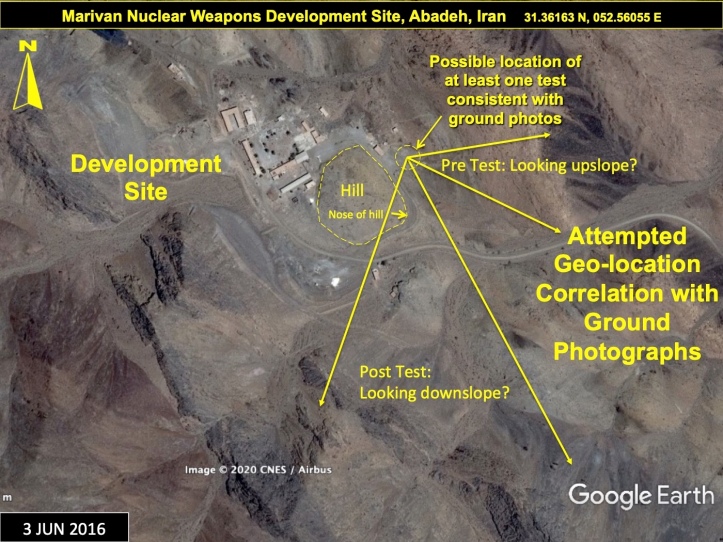

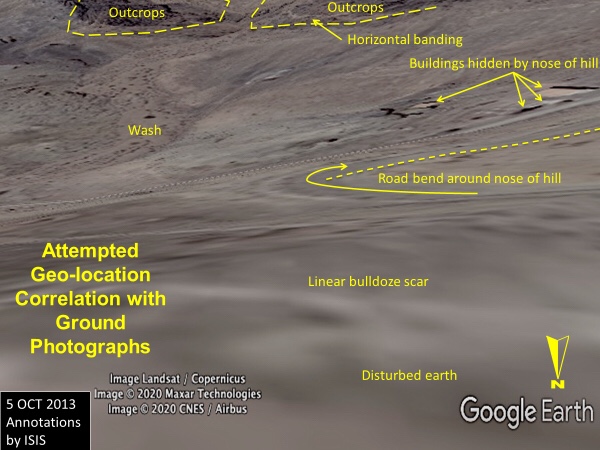

The Institute undertook an effort to geo-locate the testing area by correlating the scenes of the backgrounds in three ground photos with what can be derived from perspective terrain views in Google Earth. The ground photos were found to be consistent with an area at Marivan (Abedeh) at the base of a steep hill and at a safe distance northeast from the main cluster of buildings. While the images were of insufficient detail and scope to exclusively limit the location to only that area, we are presenting this correlation in the hope that it might prove useful to any future investigations, particularly to any future IAEA onsite visit.

Figure 8 provides an overview of the area that best matches the pre- and post-test ground images shown in Figures 6 and 7. Figure 9 provides a Google Earth perspective view from ground level looking to the south (bottom), which correlates reasonably well with the post-test ground photo (top).

Figure 8.An overview of an outdoor area at the identified Marivan Development Site near Abadeh, northeast of the main cluster of buildings and consistent with background terrain observed in the ground photos of the testing location.

Figure 9. A direct comparison of the terrain as viewed in a ground photo from the Nuclear Archive slide set “Marivan Test Results” (above) and in Google Earth (below). The Google Earth terrain model is not perfect, e.g., the nose of the hill does not adequately mask the buildings near the security checkpoint, which in reality are nearly completely hidden in the ground photo.

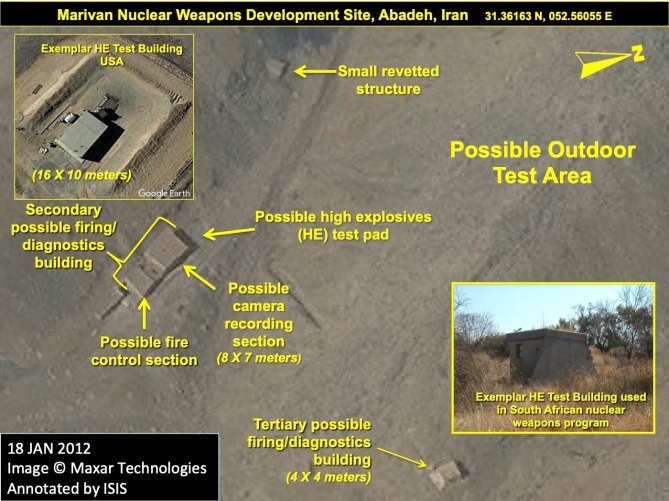

Figures 10 and 11 are close-up satellite images of the identified possible test location that provide new labeling for some of the associated structures nearby should this indeed be a high explosives testing location. Those structures could include a possible camera building that is uphill to the north west of, and approximately 40 meters from, the identified possible test location. There is also a possible firing/diagnostics building nearby with what was a circular tank, for unknown purposes, which is located between the two buildings. Most interestingly, a possible cable trench between the testing location and the possible firing/diagnostics building can be seen.

Figure 10. Buildings near the possible outdoor testing area, before Iran razed/damaged them in July 2019, could have included a camera building and a fire control/diagnostics building.

Figure 11. A January 2006 Maxar Technologies satellite image showing a possible trench for cabling running from the primary possible fire control/diagnostics building to the possible outdoor testing location.

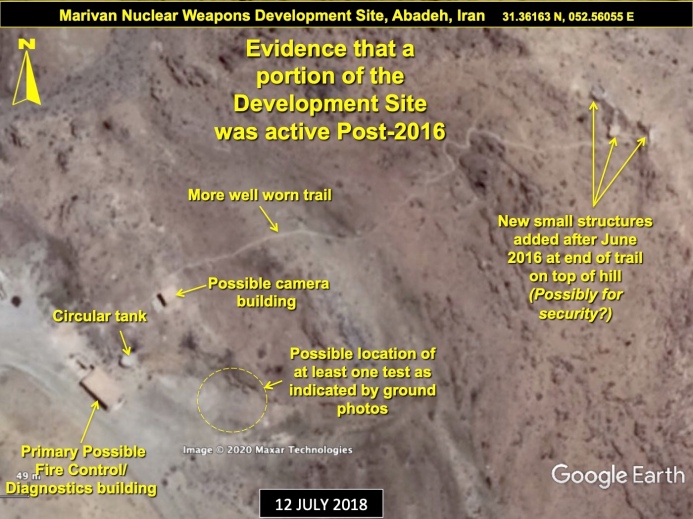

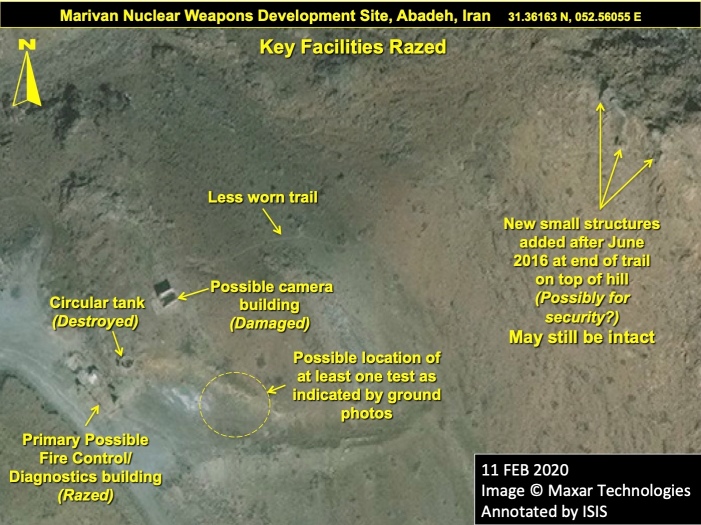

Figure 12 shows some personnel tracking in the immediate area post-2016 through 2018 and some new, small structures along the ridge top of the adjacent steeply rising mountain to the east, possibly for improved site security. Figure 13 shows the remnants of the buildings near the possible experimental location, razed by Iran in July 2019.

Figure 12. A 2018 Google Earth image shows a previously faint trail well worn, as well as structures not visible in a June 2016 image, indicating at least light activity at the site as recent as post-2016.

Figure 13. Iran razed the Marivan site abruptly in July 2019, including several key features near the possible outdoor high explosives testing area.

Another Potential Outdoor High Explosives Test Area

Figure 14, a January 2012 image, focuses on an area located northwest of the Marivan site that could have also been involved in such high explosives testing. The area, labeled “possible outdoor test area,” consists of two candidate facilities. The first one, now labeled as the “secondary possible firing/diagnostics building,” exhibited some of the characteristics one might expect for a hydrodynamic test facility with a fire control room section situated behind a potential camera recording section facing an open pad that could be used to conduct high explosives testing at close range uphill and away from the rest of the site. The primary building has a middle section with no walls, making it look like the fire control section would be shock isolated (the center section was effectively just a corridor) from the camera room section, which would be taking the main shock from any explosive detonations. A tertiary possible firing/diagnostics building (a single, small, outlier building) is located in a small isolated valley to the north of the primary one.

Figure 14. A close-up of the previously identified possible outdoor high explosives testing area when the area was intact before razing that occurred in July 2019.

Struggle to Locate Marivan

Putting all the pieces together of Iran’s nuclear weapons efforts is complicated, made more difficult by Iran’s incessant dissembling and falsehoods. Marivan is no exception.

The IAEA earlier published erroneous information about the location of the Marivan site based on a presumption that the name was that of a location rather than a project. The 2011 IAEA special report 15 reported on information supplied by an unnamed member state suggesting that the region of Marivan (on the western border of Iran) might be the location for large-scale multipoint high hemispherical explosives testing conducted in 2003. The original IAEA information described a specialized test of a multi-point initiation (MPI) system “at Marivan”.

Subsequent reporting shows that the IAEA no longer believed that association of Marivan was suggestive of the region of Marivan, but rather that it was the name of a development project as is now known from the Nuclear Archives. 16

According to a 2015 IAEA report: “The Agency has reassessed that this experiment was conducted at a location called ‘Marivan’, and not conducted in ‘the region of’ Marivan [as previously reported].” 17

Evidently the original information received by the IAEA did not contain the site’s location, and initially its location was confused with the region of Marivan, near the Iraqi border, a confusion upon which Iran tried to capitalize, urging the IAEA to inspect the Marivan region on numerous occasions, 18 resulting in the dismissal of the existence of the whole site even by some Western voices in the non-proliferation community, both at the time, 19 and as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was being finalized in late 2015. 20 For example, Iran appeared eager to allow the IAEA to visit the Marivan region in 2014, when Iran’s Ambassador to the IAEA, Reza Najafi, expressed Iran’s readiness to give the IAEA “one managed access” on a “voluntarily basis” to Marivan, adding “such alleged experiments could easily be traced if the exact site would be visited.” 21 The identification of Abadeh as being the location of “Marivan” was only established after the dissemination of the Nuclear Archive in 2018.22 It took repeated requests by the IAEA and considerable international pressure, including an IAEA Board of Governors Resolution, before Iran agreed to allow a visit. While the issue of access is hopefully resolved, the underlying issue of the incompleteness of Iran’s nuclear declaration about Marivan and a host of other sites and activities, all previously dedicated to a covert, and illegal, nuclear weapons program, is far from settled.

1. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Frank Pabian, and Andrea Stricker, “Iran Defies the International Atomic Energy Agency: The IAEA’s Latest Iran Safeguards Report,” Institute for Science and International Security, June 10, 2020, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/iran-defies-the-international-atomic-energy-agency/

2. “Joint Statement by the Director General of the IAEA and the Vice-President of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Head of the AEOI,” August 25, 2020, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/joint-statement-by-the-director-general-of-the-iaea-and-the-vice-president-of-the-islamic-republic-of-iran-and-head-of-the-aeoi

3. “Natanz’s incident an act of sabotage: AEOI spokesman,” ISNA, August 24, 2020, https://en.isna.ir/news/99060302390/Natanz-s-incident-an-act-of-sabotage-AEOI-spokesman

4. IAEA, NPT Safeguards Agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran, GOV 2020/30, June 5, 2020.

5. Raphael Ahren, “Netanyahu reveals site where Iran ‘experimented on nuclear weapons development,” The Times of Israel, September 9, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/pm-reveals-secret-site-where-iran-experimented-on-nuclear-weapons-development/

6. David Albright and Sarah Burkhard, “Intensive Nuclear Weapons Component Testing Campaign during the Amad Plan,” Institute for Science and International Security, March 5, 2020, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/intensive-nuclear-weapons-component-testing-campaign-during-the-amad-plan/8

7. “Intensive Nuclear Weapons Component Testing Campaign during the Amad Plan.”

8. More details about the Parchin and Sanjarian sites can be found in: David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, Olli Heinonen, and Frank Pabian, “New Information about the Parchin Site,” Institute for Science and International Security, October 23, 2018, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/new-information-about-the-parchin-site/8 and David Albright and Olli Heinonen, “Shock Wave Generator for Iran’s Nuclear Weapons Program,” Institute for Science and International Security, May 7, 2019, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/shock-wave-generator-for-irans-nuclear-weapons-program-more-than-a-feasibil/8

9. David Albright, Sarah Burkhard, and Frank Pabian, “The Alleged Nuclear Weapons Development Site near Abadeh, Iran,” Institute for Science and International Security, June 10, 2020, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/the-alleged-nuclear-weapons-development-site-near-abadeh-iran

10. David Albright, Paul Brannan, Mark Gorwitz and Andrea Stricker, “ISIS Analysis of IAEA Iran Safeguards Report: Part II – Iran’s Work and Foreign Assistance on a Multipoint Initiation System for a Nuclear Weapon,” November 14, 2011, Institute for Science and International Security, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/irans-work-and-foreign-assistance-on-a-multipoint-initiation-system-for-a-n/

11. Details about Iran’s shock wave generator can be found in: “Shock Wave Generator for Iran’s Nuclear Weapons Program,” https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/shock-wave-generator-for-irans-nuclear-weapons-program-more-than-a-feasibil/8

12. IAEA, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran, GOV/2011/65, November 8, 2011, http://www.isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_Iran_8Nov2011.pdf

13. IAEA Director General, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran, GOV/2011/65.

14.Nicolai P. Kozeruk, V. V. Danilenko, and I. V. Telichko, “Optical fiber gauges for gas-dynamic investigations,” Proc. SPIE 1801, 20th International Congress on High Speed Photography and Photonics (January 1, 1993); doi: 10.1117/12.145759; https://doi.org/10.1117/12.145759; and Nicolai P. Kozeruk, V. V. Danilenko, Boris V. Litvinov, P. P. Lysenko, I. V. Sanin, S. V. Samylov, V. I. Tarzhonov, and I. V. Telichko, “Multichannel optical fiber system to measure time intervals in investigations of explosive phenomena,” Proc. SPIE 1801, 20th International Congress on High Speed Photography and Photonics (January 1, 1993); doi: 10.1117/12.145729; https://doi.org/10.1117/12.145729

15. IAEA, Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran, GOV/2011/65.

16. Intensive Nuclear Weapons Component Testing Campaign during the Amad Plan, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/3653

17. IAEA Director General, Final Assessment on Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme, GOV/2015/68, December 2, 2015, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gov-2015-68.pdf

18. Iran’s former Ambassador to the IAEA, Reza Najafi said, “Such alleged experiments could easily be traced if the exact site would be visited.” See: “Iran Offers IAEA Access to Marivan Site,” Tasnim News Agency, November, 21, 2014, https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2014/11/21/564281/iran-offers-iaea-access-to-marivan-site

21. “Iran Offers IAEA Access to Marivan Site,” November 21, 2014.

22. The ground images were acquired by the Institute on August 26, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment