DUBAI, United Arab Emirates — A mysterious explosion and fire at Iran’s main nuclear facility may have stopped Tehran from building advanced centrifuges, but it likely has not slowed the Islamic Republic in growing its ever-increasing stockpile of low-enriched uranium.

Limiting that stockpile represented one of the main tenets of the nuclear deal that world powers reached with Iran five years ago this week — an accord which now lies in tatters after President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew America from it two years ago.

The larger that stockpile grows, the shorter the so-called “breakout time” becomes — time that Iran would need to build a nuclear weapon if it chooses to do so. And while Tehran insists its atomic program is for peaceful purposes, it has renewed threats to withdraw from a key nonproliferation treaty as the U.S. tries to extend a U.N. arms embargo on Iran due to expire in October.

All this raises the risk of further confrontation in the months ahead.

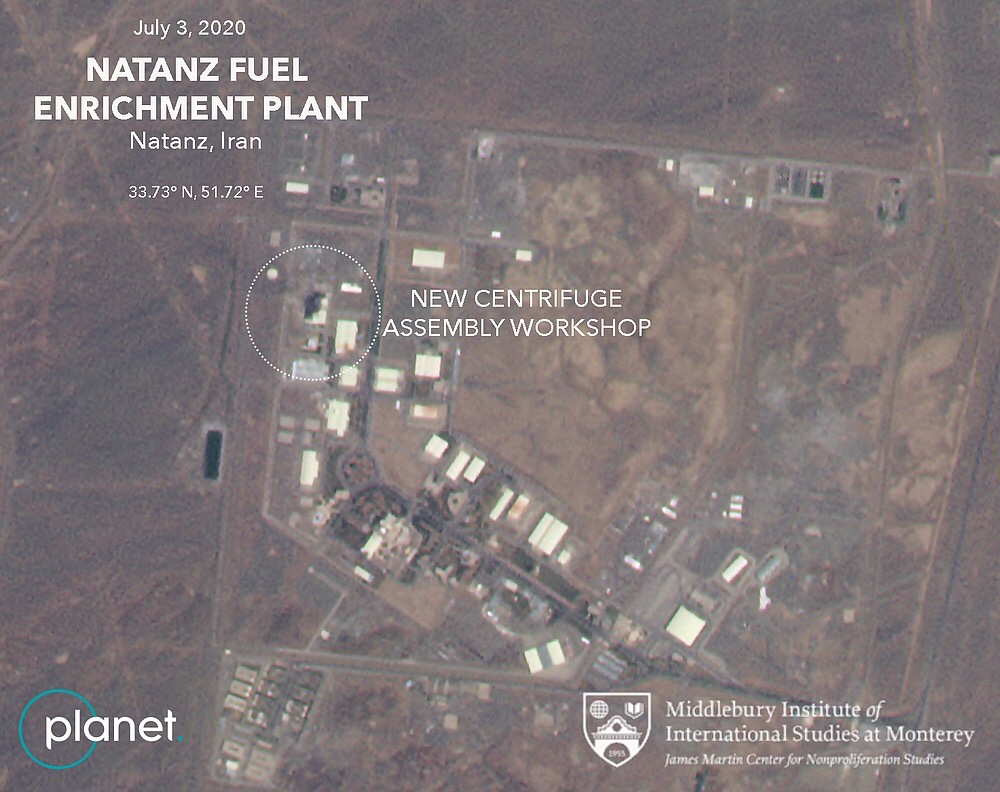

Iranian officials likely recognized that as they realized the scope of the July 2 blast at the Natanz compound in Iran’s central Isfahan province. They initially downplayed the fire, describing the site as a “shed” even as analysts immediately told The Associated Press that the blast struck Natanz’s new advanced centrifuge assembly facility.

Days later, Iran acknowledged the fire struck that facility and raised the possibility of sabotage at the site, which was earlier targeted by the Stuxnet computer virus. Still, it has been careful not to directly blame the U.S. or Israel, whose officials heavily hinted they had a hand in the fire. A claim of responsibility for the attack only raised suspicions of a foreign influence in the blast.

A direct accusation by Tehran would increase the pressure on Iran’s Shiite theocracy to respond, something it apparently does not want to do yet.

The explosion and fire, however, did not strike Natanz’s underground centrifuge halls. That’s where thousands of first-generation gas centrifuges still spin, enriching uranium up to 4.5% purity. Meanwhile, enrichment also has resumed at Iran’s Fordo nuclear facility, built deep inside a mountain to protect it from potential airstrikes. Iran continues to experiment with previously built advanced centrifuges as well.

The explosion “at Natanz was above all a blow to Iran’s plans to move on to more advanced stages in its nuclear project,” wrote Sima Shine, the head of the Iran program at the Institute for National Security Studies in Israel who once worked in the country’s Mossad intelligence service.

Shine cautioned: “However, it will not prevent Iran’s continued accumulation of enriched uranium, underway since Iran began its gradual violations of the nuclear agreement.”

As of June, the International Atomic Energy Agency said Iran had over 1,500 kilograms (3,300 pounds) of low-enriched uranium. The 2015 accord limited Iran to having only 300 kilograms (661 pounds) of uranium enriched to only 3.67%, far below weapons-grade levels of 90%.

Now at 1,500 kilograms, Iran has enough material for a single nuclear weapon if it decides to pursue one. However, that stockpile still is far less than in the days before the 2015 deal, when Tehran had enough for over a dozen bombs and chose not to weaponize its stockpile.

Iran would also need to further enrich that uranium, which would draw the attention of international inspectors still able to access its atomic facilities,. And it would still need to build a bomb. But the “breakout time” Iran would require to assemble a weapon — estimated to be at least a year under the 2015 deal — has narrowed.

All this comes after a series of incidents last year culminated in a U.S. drone strike that killed a top Iranian general in Baghdad in January, followed by a retaliatory Iranian ballistic missile attack targeting American troops in Iraq. Those tensions remain even today as the coronavirus pandemic engulfs both the U.S. and Iran.

Iran has already signaled willingness to use its nuclear program as a lever as a longstanding United Nations arms embargo on Tehran is set to expire in October. That ban has barred Iran since 2010 from buying major foreign weapon systems such as fighter jets and tanks.

Iran has threatened to expel IAEA inspectors and withdraw from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty amid the U.S. pressure campaign. North Korea, which now has nuclear weapons, is the only country to ever withdraw from the treaty.

Expelling IAEA inspectors and potentially shutting down their cameras now watching Iranian nuclear facilities would blind them from being able to see if Iran pushes its uranium enrichment closer to weapons-grade levels. But that also could see Iran alienate China and Russia, which have both urged all parties to remain in the nuclear deal.

The U.S. hopes to extend the embargo, calling Iranian threats over it being renewed a “mafia tactic.” But Washington has issued its own threats, claiming it could invoke the “snapback” of all U.N. sanctions on Iran that were eased under nuclear deal unless the embargo is prolonged — despite having left the atomic accord.

As Trump campaigns ahead of a November election, he may be more willing to take those risks to highlight that he followed through on his 2016 campaign promise to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal and take a harder line on Tehran.

The Islamic Republic in turn may be more willing to take risks as well.

“The U.S. diplomatic campaign, as well as suspected Israeli sabotage and continued attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq, will raise overall tension with Iran and introduce new uncertainty into the calculations of the Iranian leadership,” the Eurasia Group warned in an analysis on Tuesday. “That could induce Iran to take more risky action in the nuclear realm, or retaliate for … snapback in Iraq or the region.”

Jon Gambrell, the news director for the Gulf and Iran for The Associated Press, has reported from each of the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, Iran and other locations across the world since joining the AP in 2006.

No comments:

Post a Comment