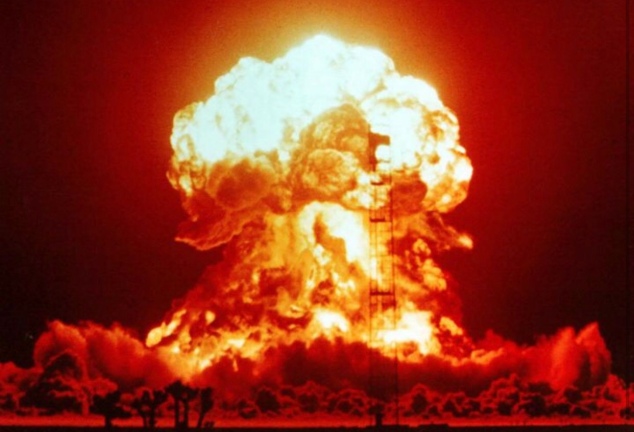

Of the two proliferations–vertical and horizontal, the latter is said to be on the strategic agenda of Pakistan. While the first is related to modernisation of nuclear arsenals by the nuclear power states, the second meant spread of nuclear-related base materials, technology and technological knowledge to aspiring nuclear weapon states and to non-state actors. If the nuclear arsenals of countries increase in size and in average weapon yield in the future, then multiple attacks on cities would become more likely in future war scenarios. This would further increase the risk of firestorms in cities suffering nuclear attack, which would increase the probability of toxic and radioactive debris reaching adjacent countries. It would also pose greater risk of regional climate disturbances arising from nuclear war. The use of weapons of mass destruction is the very worst way for nations to solve international disputes.

In context of Pakistan’s ambitious nuclear agenda is now drawing a not-so-unwilling Sri Lanka into the brewing nuclear whirlwind in south Asia. Evidently, ‘Pakistan is all set to begin consultations with Sri Lanka to help set up a nuclear power plant in Trincomallee’s,Sampur.

A hurt and frustrated Sri Lanka, so rendered by the outcome of the recently concluded United Nations Human Rights Commission (UNHRC) session, in all probability is very enthusiastic about the proposed venture, not so much because of the economic benefits it will bring about as it is because of the opportunity this new partnership presents to avenge the isolation, she suffered at the hands of India at said session.

Added to this impending disaster is the more immediate issue of deviating state capital away from poverty alleviation. It is therefore, imperative for all South Asian states to appreciate that compromising regional solid will amount to compromising the interests of individual states.

Although, the issue of nuclear proliferation remained at alert regionally and globally, the nuclear test by North Korea in October 2006, put renewed focus on the dangers of nuclear proliferation. Following the test, New Delhi swiftly condemned the test and indirectly highlighted Islamabad’s contribution to Pyongyang’s nuclear test.

On the other hand, Islamabad refuted any suggestion that the activities of the A.Q. Khan network had contributed to the said test and stated that North Korea’s nuclear programme is based on plutonium while Pakistan relies on uranium.

In this manner, for time being, both India and Pakistan tried to ensure that proliferation in South Asia was not equated with proliferation in North-east Asia. To a certain extent, the Bush administration obliged the sub-continental nuclear powers, as senior officials dismissed any parallels between North Korea’s path to nuclear weapons to those of India and Pakistan.

In the context, while Pakistan denied any links to the test, it did not help Islamabad’s case when Japanese sources stated that days before Pyongyang’s test, several Pakistani nuclear technicians arrived in North Korea through China. This augmented the suspicions that Pakistani agencies may have had some role in the test, perhaps through data sharing before or after explosion.

Role of Khan’s network

The A.Q. Khan’s network which provided nuclear assistance to North Korea and Iran has represented the most serious proliferation problem in recent years. Since Khan’s public confession in February 2004, Musharraf regime has consistently asserted that this network was the work of a rogue scientist and that the Pakistani government and its military leaders were not involved in these activities.

Analysts and officials in Pakistan as well as in the United States have expressed scepticism over Khan’s confession and the implicit professed innocence of the Pakistani political and military establishment. A highly publicised report released in April 2007 by the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, also stated that individuals and entities involved in the network could still be dormant and can conceivably be reactivated in the future.

Moreover, A.Q. Khan claimed in a signed statement that successive army chiefs in the 1990s, Generals MirzaAslam Beg and JehangirKaramat, had authorised the sales of nuclear technology. While this could be taken as Khan’s attempts to remove the burden of guilt, it is true that the military was closely associated with the nuclear and missile programmes.

In fact, in 1990, General Beg warned US government officials that Pakistan would be forced to provide nuclear technology to Tehran if Washington did not offer support to Pakistan. Other circumstantial evidence, such as visits by the Pakistani military leadership to North Korea throughout the nineties, suggests that there was a barter deal between Pyongyang and Islamabad.

Additionally, in August 2005, General Musharraf conceded that Khan had transferred centrifuge machines to North Korea through which uranium hexafluoride can be enriched for eventual processing into civilian reactors fuel or for military purposes.

Shipping out such large centrifuge machines without the military’s knowledge would have been impossible. For a country to acquire a nuclear delivery system, the decision-making process incorporates several factors, as well as the opinions of numerous government agencies to ensure compatibility among the various systems.

Dangers ahead

The issue of the Pakistani military-scientific establishment’s involvement or endorsement in the Khan’s network activities is crucial due to its implications for contemporary proliferation routes and processes. If these elements within and outside Pakistan and their methods and routes remain undiscovered, it has two broad consequences for proliferation in South Asia.

First, it allows Islamabad to potentially procure missile and nuclear technology in the future, in an attempt to catch-up with India. In this regard, a Pakistani national, Mohammed Aslam, working at the Tabani Corporation’s Moscow office, was named by the Russian government in 2006 as having attempted to acquire dual-use technology and other materials for Pakistan’s nuclear and missile development programmes.

Given Islamabad’s need to construct a secure deterrent against India, especially long-range missiles that can reach southern and eastern India, it is possible that the said case is an instance of continuing efforts to exploit non-state networks to procure prohibited equipment.

Author is Head of Department of Political Science, BNMU, West Campus, Saharsa, Bihar

No comments:

Post a Comment