Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Marc Champion

January 19, 2020, 8:30 PM MST

Rouhani policies discredited by collapse of 2015 nuclear deal

On Monday, Iran threatened to withdraw from its last remaining commitments to the 2015 deal that limited its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of international sanctions. On the same day, Foreign Minister Javad Zarif pulled out of this week’s World Economic Forum, the global economy’s annual networking event in Switzerland.

The moves follow a speech by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Friday, in which he accused Europe of joining the U.S. campaign to “bring Iran to its knees.” His regime had hoped the so-called EU-3 — Britain, France and Germany — would help Iran to circumvent U.S. President Donald Trump’s return to “maximum pressure” sanctions by upholding the nuclear deal. But that no longer seems feasible, if it ever was.

The EU-3 last week said they would trigger a dispute mechanism at the United Nations Security Council that’s likely to finally kill the so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. The deal lay at the heart of President Hassan Rouhani’s strategy of opening up to international markets in order to answer the Islamic Republic’s perennial dilemma of how to meet popular economic expectations, while still maintaining defiance of the U.S.

Khamenei, in the first Friday prayers he has led since 2012, was responding to the Jan. 3 killing of one of his most powerful generals, Qassem Soleimani, by the U.S. Yet that may have been a less important shock for Iran than November’s anti-government protests against a fuel price increase that swept poor suburbs and cities around the nation of 84 million. Hundreds were killed in a brutal crackdown.

Parliamentary polls on Feb. 21 will launch a new political cycle that, by the time a new president is elected next year, is expected to put conservatives fully in charge of the Islamic Republic. Absent a major escalation of hostilities with the U.S., their biggest challenge will again be to revive an economy that is failing the poor constituents the 1979 revolution claimed to represent. The debate over how to do that is already raging.

“We have to work with the world,” Rouhani said Thursday, in what amounted to a plaintive, hour-long defense of his legacy at the nation’s central bank. To opponents who argue that Iran can succeed in isolation, ignoring the impact of foreign policy choices, he said: “Well, I don’t know how to do that.”

The response was swift. “The revolutionary youth know how. With the help of people anything is possible,” Mohammadbagher Ghalibaf, a former Tehran mayor, ex-Revolutionary Guard officer and three-time presidential candidate, wrote in a tweet.

Many conservatives interpret Khamenei’s ambiguous calls for a “resistance economy” to mean adjustment to sanctions through import substitution, coupled with reliance on China and Russia for investment and technology transfers.

The catch is that sanctions are only part of the problem in a country with sometimes difficult business conditions and a weak private sector, according to Cyrus Razzaghi, president of Ara Enterprise, a business consultancy in Tehran. Nor can China alone provide all the funds and technologies Iran requires to prosper.

“What’s needed is really massive structural reforms to make Iran more productive, with or without sanctions,” he said. “To be honest, I don’t see any manifesto or real policy to address these issues.”

The central bank said last week it was taking action to make it easier for private companies to export. Private companies are responsible for much of the $40 billion worth of non-oil goods Iran is still managing to send abroad annually, securing vital hard currency, the bank said.

In many ways, the surprise is that Iran’s economy has survived as well as it has.The rial has stabilized after losing more than half its value when Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal in 2018. Middle class Iranians are scraping by.

Without dramatic external or internal relief for the economy, this resilience can’t last forever, Razzaghi said. He puts the limit somewhere in 2021. That economic fragility also means Iran “can’t afford further military escalation” with the U.S., Ziad Daoud of Bloomberg Economics said.

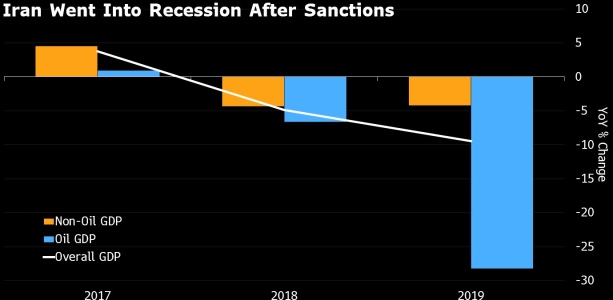

The economy has been badly damaged by the renewed sanctions,reimposed at a time when a lower oil price was in any case squeezing government revenue. During the last U.S.-led sanctions campaign against Iran, before the 2015 nuclear deal, former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad showered the population with handouts. That was made possible largely by an oil price around $120 per barrel. Oil has been closer to $60 per barrel for much of Rouhani’s term.

Iran’s Sanctions Ride

Where Ahmadinejad doled out what amounted to helicopter cash, his successor has sought to rein in public subsidies. It was the rationing of cheap gasoline that sparked November’s violent protests among the poor.

More recent demonstrations, in response to Iran’s admission that it shot down a Ukrainian airliner on Jan. 8, killing all 176 on board, have been led by mainly middle class students. So far, they’ve been more easily managed by security forces. What would really be a problem for the regime “is if we see these two groups merge,” says Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi, an Iran specialist at the Royal United Services Institute in London.

Riot police and demonstrators gather near Tehran’s Amir Kabir University on Jan. 11.

The economy could be on borrowed time because of the severity of sanctions, Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, professor of economics at Virginia Tech, said even though he’s more upbeat about the government’s economic management. In a country with an implicit social contract that exchanges acceptance of the Islamic Republic’s ideological strictures for prosperity, the kind of belt tightening that a resistance economy demands could be a hard sell.

“The future is really going to be determined by two issues,” said Salehi-Isfahani. “Will Iranian producers be able to produce? That takes reforms. And can they export some of that? Because any economy needs foreign exchange.”

None of this means regime change is nearing in Iran. And if Iran’s leaders fail that challenge, a number of things still militate against the country descending into any Venezuela-style meltdown, according to Ellie Geranmayeh, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at the European Council on Foreign Relations in Brussels.

One reason is that, post-Ahmadinejad, the government is much more fiscally conservative. That makes hyperinflation less likely. Iran has also had more success than its Arab neighbors in diversifying the economy away from a dependence on oil.

But perhaps the biggest difference with Venezuela is Iran’s strategically important location. Not only is it on the Gulf, critical to global oil markets, it also borders Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, while straddling a planned leg of China’s Belt and Road to Europe.

“There will be geopolitical incentives, for Russia and China to ensure that U.S. sanctions do not completely cripple Iran’s economy,” Geranmmayeh said.

— With assistance by Golnar Motevalli

(Updates with latest comments on nuclear deal, Zarif’s Davos pullout in second paragraph)

No comments:

Post a Comment