A couple of hundred thousand years ago, an M 7.2 earthquake shook what is now New Hampshire. Just a few thousand years ago, an M 7.5 quake ruptured just off the coast of Massachusetts. And then there’s New York.

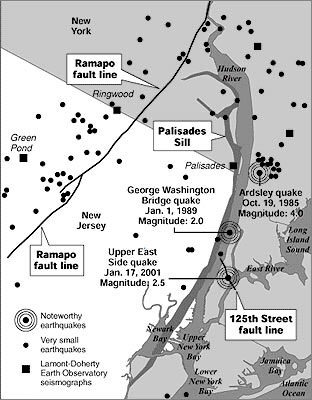

Since the first western settlers arrived there, the state has witnessed 200 quakes of magnitude 2.0 or greater, making it the third most seismically active state east of the Mississippi (Tennessee and South Carolina are ranked numbers one and two, respectively). About once a century, New York has also experienced an M 5.0 quake capable of doing real damage.

The most recent one near New York City occurred in August of 1884. Centered off Long Island’s Rockaway Beach, it was felt over 70,000 square miles. It also opened enormous crevices near the Brooklyn reservoir and knocked down chimneys and cracked walls in Pennsylvania and Connecticut. Police on the Brooklyn Bridge said it swayed “as if struck by a hurricane” and worried the bridge’s towers would collapse. Meanwhile, residents throughout New York and New Jersey reported sounds that varied from explosions to loud rumblings, sometimes to comic effect. At the funeral of Lewis Ingler, a small group of mourners were watching as the priest began to pray. The quake cracked an enormous mirror behind the casket and knocked off a display of flowers that had been resting on top of it. When it began to shake the casket’s silver handles, the mourners decided the unholy return of Lewis Ingler was more than they could take and began flinging themselves out windows and doors.

Not all stories were so light. Two people died during the quake, both allegedly of fright. Out at sea, the captain of the brig Alice felt a heavy lurch that threw him and his crew, followed by a shaking that lasted nearly a minute. He was certain he had hit a wreck and was taking on water.

A day after the quake, the editors of The New York Times sought to allay readers’ fear. The quake, they said, was an unexpected fluke never to be repeated and not worth anyone’s attention: “History and the researches of scientific men indicate that great seismic disturbances occur only within geographical limits that are now well defined,” they wrote in an editorial. “The northeastern portion of the United States . . . is not within those limits.” The editors then went on to scoff at the histrionics displayed by New York residents when confronted by the quake: “They do not stop to reason or to recall the fact that earthquakes here are harmless phenomena. They only know that the solid earth, to whose immovability they have always turned with confidence when everything else seemed transitory, uncertain, and deceptive, is trembling and in motion, and the tremor ceases long before their disturbed minds become tranquil.”

That’s the kind of thing that drives Columbia’s Heather Savage nuts.

Across town, Charles Merguerian has been studying these faults the old‐fashioned way: by getting down and dirty underground. He’s spent the past forty years sloshing through some of the city’s muckiest places: basements and foundations, sewers and tunnels, sometimes as deep as 750 feet belowground. His tools down there consist primarily of a pair of muck boots, a bright blue hard hat, and a pickax. In public presentations, he claims he is also ably abetted by an assistant hamster named Hammie, who maintains his own website, which includes, among other things, photos of the rodent taking down Godzilla.

That’s just one example why, if you were going to cast a sitcom starring two geophysicists, you’d want Savage and Merguerian to play the leading roles. Merguerian is as eccentric and flamboyant as Savage is earnest and understated. In his press materials, the former promises to arrive at lectures “fully clothed.” Photos of his “lab” depict a dingy porta‐john in an abandoned subway tunnel. He actively maintains an archive of vintage Chinese fireworks labels at least as extensive as his list of publications, and his professional website includes a discography of blues tunes particularly suitable for earthquakes. He calls female science writers “sweetheart” and somehow manages to do so in a way that kind of makes them like it (although they remain nevertheless somewhat embarrassed to admit it).

It’s Merguerian’s boots‐on‐the‐ground approach that has provided much of the information we need to understand just what’s going on underneath Gotham. By his count, Merguerian has walked the entire island of Manhattan: every street, every alley. He’s been in most of the tunnels there, too. His favorite one by far is the newest water tunnel in western Queens. Over the course of 150 days, Merguerian mapped all five miles of it. And that mapping has done much to inform what we know about seismicity in New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment