Is Pakistan's nuclear stock safe?

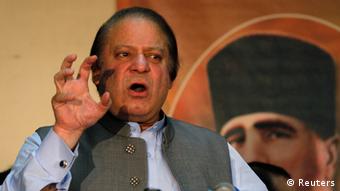

Pakistani Prime Minister Sharif has assured the world after visiting the

country's nuclear control authority that the Islamic republic's atomic

weapons are protected. Some security experts, however, are not

convinced.

It is not the first time that a Pakistani leader has told the world that

the country's nuclear arsenal is in safe hands. Despite these repeated

assurances, the West has been worried about the safety of Pakistan's

atomic weapons for quite some time. Pakistan, which conducted its only

nuclear tests in 1998, is battling with a protracted Islamist insurgency

which threatens to paralyze the state. In the past decade, Islamists

not only attacked civilians but targeted military installations and

bases as well. Some international experts say that the Taliban and al

Qaeda have their eyes on Pakistan's nuclear warheads.

Last week, Prime Minister Sharif visited the country's National Command Center, which oversees Pakistan's nuclear facilities. The PM was accompanied by officials from the powerful Pakistani military, which experts say has the last word when it comes to matters related to defense and security. After the visit, the premier said Islamabad wanted "peace in the region, and would not be part of an arms race." He said further that the country's nuclear arsenal was "well protected."

Islamabad-based defense analyst Maria Sultan agrees with the PM and says Pakistan's nuclear control authorities have a strong grip on the country's nuclear assets. "Pakistan has the capability of monitoring its nuclear weapons, and the technology it is using to do that is very sophisticated," Sultan told DW. She insisted that the West's concerns about Pakistan's nuclear safety were "unfounded."

'Talibanization of the military'

Though Pakistan's civilian and military establishments claim their nuclear weapons are under strict state control, many defense experts fear that they could fall into the hands of terrorists in the event of an Islamist takeover of Islamabad or if things get out of control for the government and the military.

"Nuclear programs are never safe. On the one hand there is perhaps a hype about Pakistani bombs in the Western media, on the other there is genuine concern," London-based Pakistani journalist and researcher Farooq Sulehria told DW. "The Talibanization of the Pakistan military is something we can't overlook. What if there is an internal Taliban takeover of the nuclear assets?" Sulehria speculated.

Sulehria's concerns are probably justified. The Taliban militants have proven time and again that they are capable of attacking not only civilians but also military bases. In August 2012, militants armed with guns and rocket launchers attacked an air base in the town of Kamra in the Punjab province. The large base is home to several squadrons of fighter and surveillance planes, which air force officials said had not been damaged in the attack. The Taliban have great influence in Pakistan's restive northwestern Swat Valley and according to defense experts, several nuclear installations are located not too far from the area.

Despite that, political and defense analyst Zahid Hussain told DW the West was "unnecessarily worried."

"Pakistan conducted its nuclear tests more fifteen years ago. Nothing has happened since then. Pakistan has made sure the nuclear weapons remain safe."

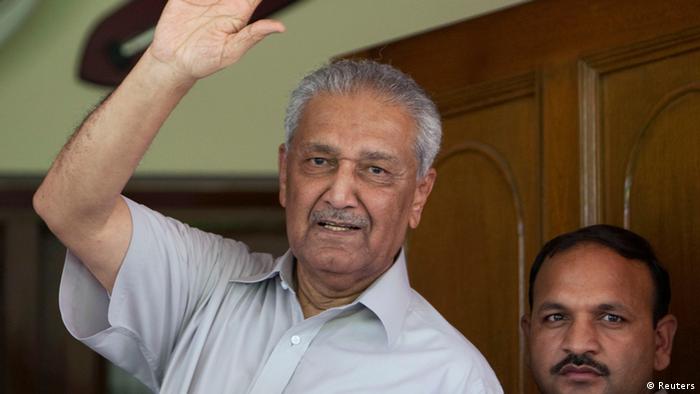

Nuclear proliferation

However, Pakistan's nuclear safety record is not as clean as Hussain claims. In 2004, the "founder" of the country's nuclear bomb Dr. A. Q. Khan confessed to selling nuclear technology to North Korea and Iran. Khan was removed from his post as head of the country's nuclear program by former military dictator and President Pervez Musharraf in 2001. Khan spent five years under house arrest after Musharraf had him arrested in 2004 for his alleged role in divulging nuclear secrets. The restrictions on his movement were relaxed after a court in Islamabad declared him a free man in 2009.

The Pakistani military and civilian leaders have been accused of being too easy on Khan, but they have defended themselves, saying that the state had no role in what they say was Khan's "individual act." But many in Pakistan and in the West believe Khan was only able to pass on such sensitive information with support from the establishment.

Khan is a popular figure among Islamists and common Pakistanis alike, who believe that nuclear weapons are "necessary" for the security of the country. Pakistan's political and religious parties invariably use nuclear rhetoric against India and Western nations.

"The atomic bomb is our protector. It guarantees our sovereignty. Nobody can harm Pakistan as long as we have this bomb, and that is the reason why the US, India and other Western countries are conspiring against it," Abdul Basit, a student at Karachi University, told DW.

Asim Uddin, a London-based Jamaat-e-Islami activist, is of the same view. He says Pakistan needs nuclear assets because it has a nuclear neighbor - India - against which it has fought three wars. "Pakistan needs nuclear weapons as a war deterrent," he told DW.

Sulehria, on the other hand, says that though the world needs to be more vigilant about Pakistan's nuclear weapons, its nuclear obsession is more about domestic politics than external threats.

"Politicians use nuclear rhetoric to appease the public. Since the 1980s, jihad has been part of the state doctrine. And for jihad, the country needs the 'ultimate weapon' -the nuclear bomb."

Experts like Sulehria fear that a crumbling economy, an ever-increasing Islamist threat, and a popular nuclear narrative are a perfect recipe for a nuclear crisis. They also say that the Pakistani government and the premier need to do a lot more than merely issuing official statements about nuclear safety.

Last week, Prime Minister Sharif visited the country's National Command Center, which oversees Pakistan's nuclear facilities. The PM was accompanied by officials from the powerful Pakistani military, which experts say has the last word when it comes to matters related to defense and security. After the visit, the premier said Islamabad wanted "peace in the region, and would not be part of an arms race." He said further that the country's nuclear arsenal was "well protected."

Islamabad-based defense analyst Maria Sultan agrees with the PM and says Pakistan's nuclear control authorities have a strong grip on the country's nuclear assets. "Pakistan has the capability of monitoring its nuclear weapons, and the technology it is using to do that is very sophisticated," Sultan told DW. She insisted that the West's concerns about Pakistan's nuclear safety were "unfounded."

'Talibanization of the military'

Though Pakistan's civilian and military establishments claim their nuclear weapons are under strict state control, many defense experts fear that they could fall into the hands of terrorists in the event of an Islamist takeover of Islamabad or if things get out of control for the government and the military.

"Nuclear programs are never safe. On the one hand there is perhaps a hype about Pakistani bombs in the Western media, on the other there is genuine concern," London-based Pakistani journalist and researcher Farooq Sulehria told DW. "The Talibanization of the Pakistan military is something we can't overlook. What if there is an internal Taliban takeover of the nuclear assets?" Sulehria speculated.

Sulehria's concerns are probably justified. The Taliban militants have proven time and again that they are capable of attacking not only civilians but also military bases. In August 2012, militants armed with guns and rocket launchers attacked an air base in the town of Kamra in the Punjab province. The large base is home to several squadrons of fighter and surveillance planes, which air force officials said had not been damaged in the attack. The Taliban have great influence in Pakistan's restive northwestern Swat Valley and according to defense experts, several nuclear installations are located not too far from the area.

Despite that, political and defense analyst Zahid Hussain told DW the West was "unnecessarily worried."

"Pakistan conducted its nuclear tests more fifteen years ago. Nothing has happened since then. Pakistan has made sure the nuclear weapons remain safe."

However, Pakistan's nuclear safety record is not as clean as Hussain claims. In 2004, the "founder" of the country's nuclear bomb Dr. A. Q. Khan confessed to selling nuclear technology to North Korea and Iran. Khan was removed from his post as head of the country's nuclear program by former military dictator and President Pervez Musharraf in 2001. Khan spent five years under house arrest after Musharraf had him arrested in 2004 for his alleged role in divulging nuclear secrets. The restrictions on his movement were relaxed after a court in Islamabad declared him a free man in 2009.

The Pakistani military and civilian leaders have been accused of being too easy on Khan, but they have defended themselves, saying that the state had no role in what they say was Khan's "individual act." But many in Pakistan and in the West believe Khan was only able to pass on such sensitive information with support from the establishment.

Khan is a popular figure among Islamists and common Pakistanis alike, who believe that nuclear weapons are "necessary" for the security of the country. Pakistan's political and religious parties invariably use nuclear rhetoric against India and Western nations.

"The atomic bomb is our protector. It guarantees our sovereignty. Nobody can harm Pakistan as long as we have this bomb, and that is the reason why the US, India and other Western countries are conspiring against it," Abdul Basit, a student at Karachi University, told DW.

Asim Uddin, a London-based Jamaat-e-Islami activist, is of the same view. He says Pakistan needs nuclear assets because it has a nuclear neighbor - India - against which it has fought three wars. "Pakistan needs nuclear weapons as a war deterrent," he told DW.

Sulehria, on the other hand, says that though the world needs to be more vigilant about Pakistan's nuclear weapons, its nuclear obsession is more about domestic politics than external threats.

"Politicians use nuclear rhetoric to appease the public. Since the 1980s, jihad has been part of the state doctrine. And for jihad, the country needs the 'ultimate weapon' -the nuclear bomb."

Experts like Sulehria fear that a crumbling economy, an ever-increasing Islamist threat, and a popular nuclear narrative are a perfect recipe for a nuclear crisis. They also say that the Pakistani government and the premier need to do a lot more than merely issuing official statements about nuclear safety.

No comments:

Post a Comment