Longitudinal Attitudes in South Korea on Nuclear Proliferation

This piece is one of 12 contributions to KEI’s special project on South Korea’s nuclear armament debate that will run on The Peninsula blog over the next month. The project’s contributors include young, emerging, and mid-career voices, examining the debate from a historical, a domestic, and an international perspective. On Wednesday, March 15, KEI will host a conference featuring our various contributors’ work at our Washington, D.C. office and launch a compilation of all the pieces in a single, special KEI publication.

Introduction

The discussion in South Korea surrounding nuclear armament has grown increasingly serious over the past decade. It went from a largely taboo subject, to one that was discussed quietly among a select group of political elites, to members of the conservative ruling party now openly calling for South Korea’s nuclear armament. Those voices are now being joined by prominent progressive-leaning foreign policy experts. Importantly, the discussion now goes beyond generic calls for acquiring nuclear weapons. And even President Yoon identified acquiring nuclear weapons as a potential policy option in the future. There is increasing attention paid to the process of how South Korea would acquire nuclear weapons, and specific details about such a plan are likely not far behind.

This mainstreaming of the nuclear debate is not an attempt to cultivate support among the South Korean public. Rather, South Korean politicians and the foreign policy elite are meeting the public where it already is. Over the past decade, broad support for a domestic nuclear weapons program has been one of the most reliable findings across public opinion surveys in South Korea. Roughly two-thirds of the South Korean public consistently supports such a program, and that support largely cuts across the country’s ferocious political and ideological divides.

This broad public support is driven, in part, by several factors: that the denuclearization of North Korea via negotiations is now seen as an impossible goal; the region is headed toward greater competition and potentially conflict; the United States is afflicted with unpredictable domestic politics; and a growing perception that China represents a significant national security threat.

Less well understood—and less tested in surveys—is the robustness of support for nuclear weapons. The public is rarely asked about the consequences of proliferating and how those consequences might influence their thinking. Moreover, the surveys that have sought to investigate this further have reached counterintuitive results.

Longitudinal Attitudes on Nuclear Weapons

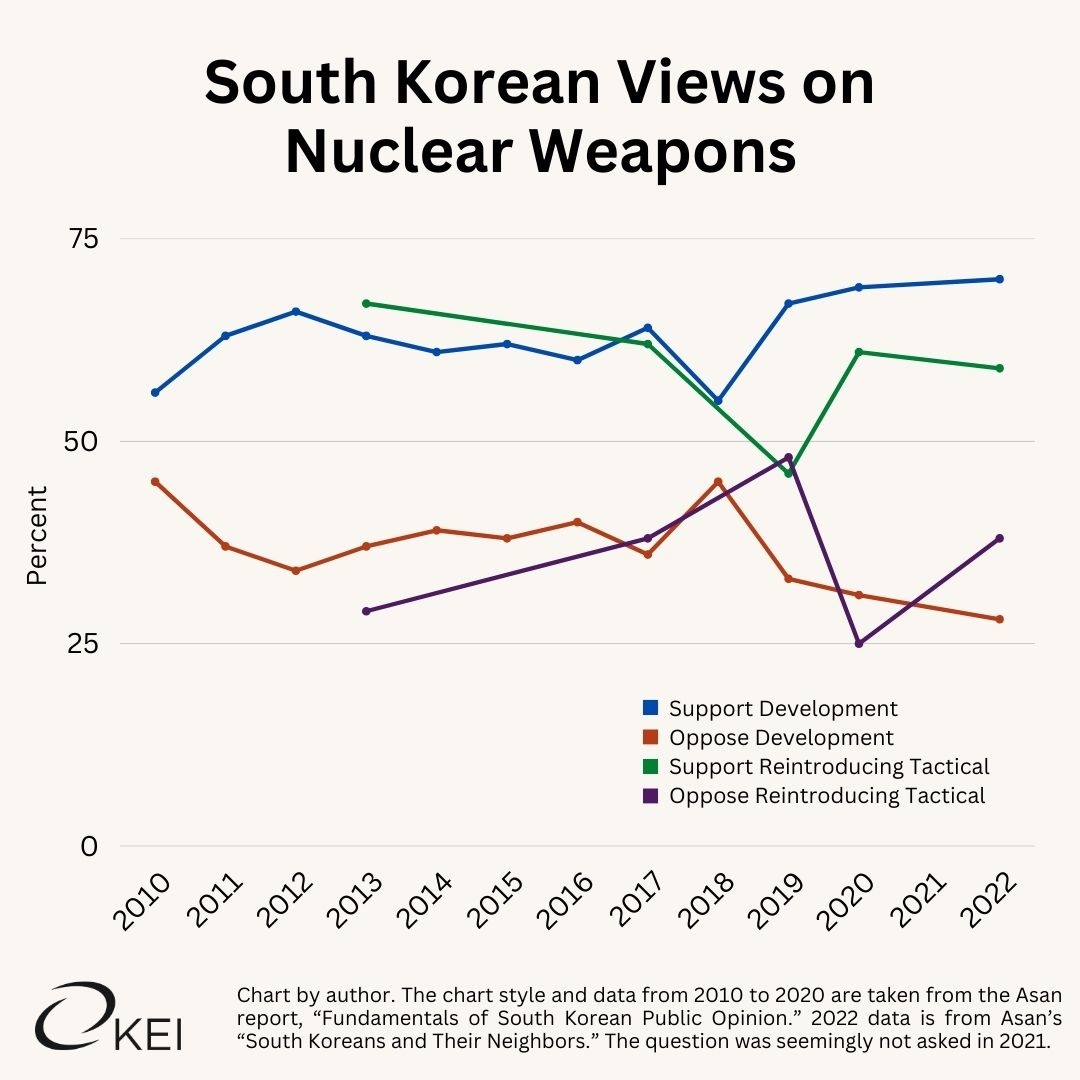

Perhaps the single-best source on South Korean attitudes towards nuclear weapons over time is polling from the Asan Institute for Policy Studies. Asan has been asking about support for domestic nuclear weapons since 2010, creating a trend data set going back more than a decade. In that data, majorities consistently support a South Korean nuclear weapons program.

There are occasional dips in that support, such as 2018, when support dipped below 60 percent for the first time since 2011. The reason for this dip is likely best explained by optimism running high due to the Singapore Summit in June between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un. The summit was officially announced in early March 2018 and the unprecedented nature of the meeting likely created widespread belief that a significant deal was possible. The Asan polling was conducted in late March and respondents would have been aware of the announcement of the Singapore Summit.

This dip in support was also apparent in polling conducted by the East Asia Institute (EAI). In a survey conducted in May 2018—after the announcement but before the summit took place in June—support for a domestic nuclear weapons program fell to 43 percent from 67 percent in 2017. The 24-percentage point drop in the EAI polling is highly unusual for polling on any topic and is a magnitude greater than the 9-percentage point drop in the Asan polling. By 2021, support for a domestic nuclear weapons program had returned to 60 percent in EAI’s polling.

More importantly, these drops in support are probably not repeatable as optimism for North Korea’s denuclearization has faded. In Chicago Council-Carnegie Endowment polling in late 2021, 83 percent said it was unlikely that North Korea would give up its nuclear weapons, with a majority (59%) saying it was very unlikely. Any future negotiations will have to contend with the legacy of the Singapore and Hanoi summits, and the public is unlikely to ever hold such optimism again.

Another notable feature of attitudes on nuclear weapons is the sheer consistency across a society with simmering societal conflicts that cut across age cohort, gender, and political ideology. Rather than divides, nuclear weapons are an area with which there is now broad societal agreement. Especially important is the agreement between supporters of the conservative People Power Party and the progressive Democratic Party. On several issues related to national security and foreign affairs, these parties take different approaches—at least rhetorically—on North Korea, China, and sometimes the United States. As of yet, nuclear weapons have not been a part of any official party platform, but that day may not be far off. And if it does come, such a platform will not be dismissed outright. Rather, the public may wonder what took so long.

Polling from the Chicago Council and Carnegie Endowment makes this broad societal agreement clear. In the late 2021 joint survey, 71 percent favored a domestic nuclear weapons program. It is also illustrated the agreement across society. Both men (76%) and women (67%) support a domestic weapons program, at least 65 percent of all age cohorts say the same, as do 67 percent of supporters of the progressive Democratic Party and 82 percent of the conservative People Power Party.

These findings were confirmed by a mid-December 2022 poll conducted by Hankook Research, with 67 percent overall in favor and majorities of all ages, regions, and party support in agreement.

Another notable feature is that support for a nuclear weapons program does not appear to be overly sensitive to question wording. The wording used by the Asan Institute positions a South Korean nuclear weapons program as a direct response to North Korea’s nuclear weapons development as does the wording used in the East Asia Institute surveys. However, the Chicago Council-Carnegie Endowment polling and the more recent Hankook Research survey omit this reference to North Korea and frames a nuclear weapons program more neutrally. Results are similar across all four surveys.

Taken together, the data suggests that the support for a domestic nuclear weapons program is robust, long-standing, and unlikely to dissipate. There is some evidence that support for a nuclear weapons program reacts inversely to hope for a breakthrough with North Korea. Across multiple surveys, support for a nuclear program dipped as the announcement of unprecedented summits led to hopes of a real breakthrough. That sets an impossibly high precedent and even if there are future summits, the effect on public opinion is unlikely to be repeated.

Hypothetical Scenarios

While baseline support for a domestic nuclear weapons program has been a standard feature of polling for at least the past decade, relatively less work has been done on the underlying reasons for support. Theories of support for hypothetical South Korean nuclear weapons range from pure self-defense to using those weapons as a bargaining tool so that North Korea and South Korea could pursue denuclearization simultaneously. There are also theories linked to U.S. credibility.

One of the most recent studies was done in 2020 by Lauren Sukin in a publication for the Journal of Conflict Resolution. In baseline questioning, Dr. Sukin’s study found that 68 percent support a nuclear weapons program, but then went on to test how those attitudes were linked to the credibility of the United States. Her findings run counter to traditional proliferation theory. That theory suggests that as U.S. credibility degrades support for nuclear proliferation will rise. Instead, she finds that the opposite is true. She calls this “unwanted use theory” which postulates that the U.S. commitment is too credible. This results in fears that the United States could escalate too quickly in a conflict with North Korea, putting South Korea at risk of nuclear retaliation from North Korea. Thus, public support for a domestic nuclear weapons program increases as U.S. credibility increases. The aim of a nuclear weapons program is thus to ensure that South Korea is more firmly in control of the decision to use nuclear weapons.

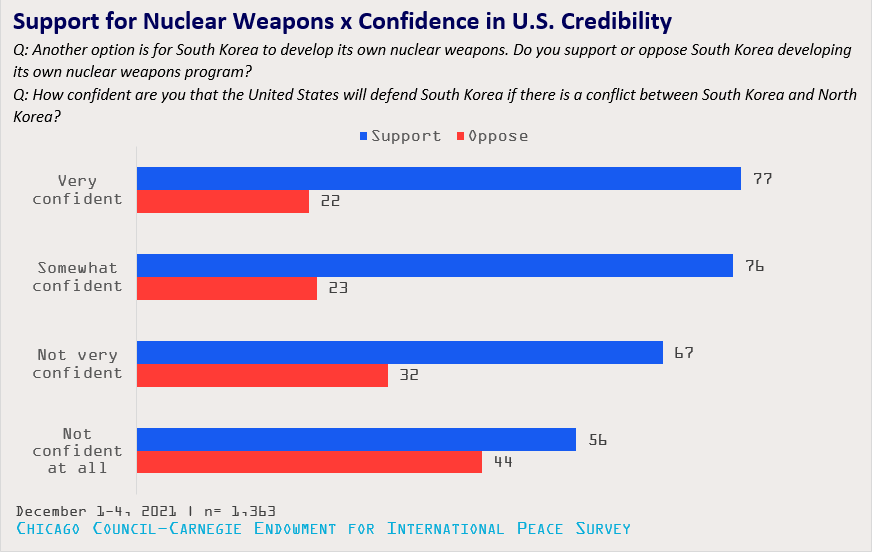

Here, the 2021 Chicago Council-Carnegie Endowment polling is instructive. Its findings align with Dr. Sukin’s unwanted use theory. For every step up in confidence in perceived U.S. credibility[1], support for nuclear weapons[2] also increases. Although, it is worth noting that majorities of all confidence levels supported a domestic nuclear weapons program.

As shown, 77 percent of those that were very confident support a nuclear weapons program as did 76 percent of those that were somewhat confident. Among those that were not very confident, that number slid to 67 percent and among those that had no confidence it was 56 percent.

A different version of this graphic appeared in a previous report by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the Carnegie Endowment for International Affairs titled Thinking Nuclear: South Korean Attitudes on Nuclear Weapons.

This puts the United States in a potential bind and highlights the public-elite divide in South Korea. As the region trends towards more conflictual relationships, South Korean elites are calling for ways to shore up the U.S. commitment to defend South Korea. This often focuses on extended deterrence and President Yoon recently claimed that South Korea and the United States were discussing joint nuclear exercises—an assertion President Biden later denied. However, extended deterrence and nuclear exercises are both beyond the understanding of the Korean public at large. But the larger message likely penetrates the public conscience—that the United States stands ready to defend South Korea if it is attacked. And as the credibility of that commitment increases, so too will South Korean support for a nuclear weapons program.

This increase in support may not manifest through ever increasing rates of support. Roughly 25 percent of the South Korean public seem to oppose nuclear weapons of any kind in South Korea. This opposition is not based on security concerns but rather on a moral opposition to nuclear weapons more broadly. This type of opposition is less likely to shift with changes in the geopolitical context. This suggests that support for nuclear weapons may already be near its ceiling barring an external shock that rapidly shifts attitudes of those that oppose nuclear weapons.

Conclusion

While it is not definitive and the subject needs further study, the data suggests that South Korea and the United States are caught in a reassurance trap. As South Korean administrations calls for nuclear exercises or even nuclear sharing with the United States in an effort to reassure the South Korean public—a public that already sees the U.S. commitment as highly credible—it will feed public concern that the United States could escalate too quickly. In turn, this will harden public support and increase political calls for nuclear armament. To undermine those calls the South Korean administration then seeks further reassurance from the United States, starting the cycle all over again.

How this cycle can be broken is not clear. The United States publicly revealing that its defense plans for South Korea does not include a nuclear response to a North Korean first would have unpredictable consequences both in South Korea and more broadly. But until the alliance can find a way to break that cycle, calls for South Korea to pursue its own nuclear weapons are going to grow louder, presenting both sides of the alliance with discussions they do not want to have and decisions they do not want to make.

Karl Friedhoff is the Marshall M. Bouton Fellow for Asia Studies at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

Photo from the U.S. Secretary of Defense’s photostream on flickr Creative Commons.

[1] Question wording: How confident are you that the United States will defend South Korea if there is a conflict between South Korea and North Korea?

[2] Question wording: Another option is for South Korea to develop its own nuclear weapons. Do you support or oppose South Korea developing its own nuclear weapons program?

No comments:

Post a Comment