Academics and arms control wonks are poring over the painfully worded text of a new Russian policy, reading the tea leaves for insights into Russian nuclear strategy. But don’t mistake this new policy document for revelations of plans, or a disclosure on the nuances of Russian nuclear strategy. Declaratory policies should be taken for the contrived signaling documents that they are, seeking to deter with ambiguity.

On June 2nd Russia released the Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Sphere of Nuclear Deterrence. Characteristically, the long and awkwardly worded title preceded a brief six-page declaratory policy that is intentionally ambiguous on key considerations, substantiating a spectrum of nuclear employment options and strategies. True to its word, the policy offers some basic principles, wrapped in normative language to forearm Russian arms control negotiators, but its contents will not settle the debate on Russian nuclear strategy anytime soon.

Russian nuclear strategy has been the subject of vigorous debates in recent years. Some believe it hides a plan to compel war termination through early use of nuclear arms after a case of aggression, i.e., escalate to de-escalate; others see it primarily as a defensive deterrent to be used in exigent circumstances. Analysts have argued that Russia’s lowered nuclear threshold is a myth, a temporary measure born out of conventional inferiority. Others believe that “escalate to de-escalate” does not exist as a doctrine, or that the term itself should be terminated because the real strategy is escalation control.

Each perspective offers a kernel of truth, but none of these views captures Russian nuclear strategy and thinking on escalation management in a satisfactory or comprehensive manner. The debate on escalate to de-escalate and Russia’s supposed lower nuclear threshold has often missed the plot and degenerated into two camps with broadly divergent interpretations. More importantly, the Russian military’s theory of victory and how it developed, or why the military thinks these specific stratagems might work, are often missing considerations.

CNA’s Russia Studies Program recently concluded a study on Russia’s strategy for escalation management, or intra-war deterrence, across the conflict spectrum from peacetime to nuclear war. The research consulted a representative sample of over 700 Russian-language articles from authoritative military publications over the past three decades. Delving into the current state of Russian military strategy and thinking on these subjects, we found that the Russian defense establishment has developed a mature system of deterrence and a coherent escalation management strategy, integrating conventional, strategic, and nonstrategic nuclear weapons. Russian thinking on deterrence and escalation management is the result of decades of debates and concept development. Official policies, strategies, and doctrines offer glints of the thinking behind Russian nuclear strategy, using refereed terms and concepts whose actual contents are discussed extensively in military writings.

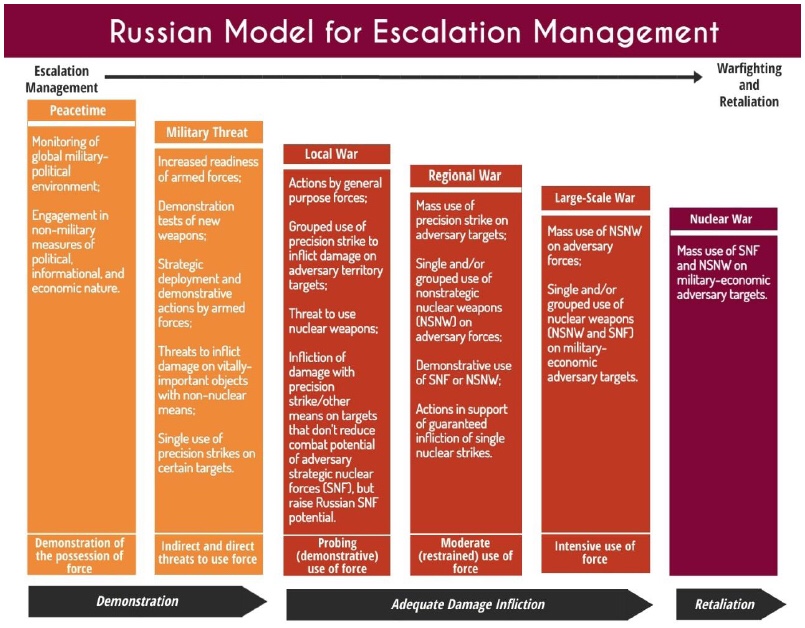

In this article we lay out key components of Russia’s nuclear strategy and thinking on escalation management, premised on deterrence by what the Russian military calls “fear-inducement” and deterrence through the limited use of force. The simplistic view characterizing Russian strategy as “escalate to de-escalate” or “escalate to win” is not correct, but neither are the commonly voiced counterarguments that suggest no Russian strategy for limited nuclear use exists, or that it was simply a stopgap measure born out of conventional inferiority. Russia does have a strategy for escalation management, seeking to dissuade, intimidate, or achieve de-escalation at key transition points and early phases of conflict, from peacetime through large-scale and nuclear war. These stratagems work by integrating the threat to inflict damage with nonnuclear and nuclear capabilities, ideas based on “dosed” damage, and applying force in a progressive manner, in an attempt to raise the adversary’s expected costs well above the desired benefits.

What Problems Is Russian Nuclear Strategy Solving?

One of the challenges in reading Russian military strategy is understanding the typology of conflicts, because different instruments or deterrence approaches are applied depending on the type of war being discussed. The Russian military doctrine breaks down conflict types into armed conflict, local war, regional war, and large-scale war. Nuclear war is imagined as a large-scale nuclear exchange or strategic nuclear retaliation. We forgo discussion of nuclear war, in which Russian strategic nuclear forces are postured to conduct a retaliatory strike, launch on attack, or, as the new state policy suggests, possibly launch on warning. This aspect of Russian nuclear strategy is not especially controversial, nor has it changed in recent years. Indeed, most official Russian statements, and stylized comments by President Vladimir Putin, try to speak only to Russia’s strategic nuclear forces posture, sidestepping the role of nonnuclear and nonstrategic nuclear weapons, while both of those arsenals grow in size.

The purpose of Russia’s escalation management strategy is to deter direct aggression, preclude a conflict from expanding, prevent or preempt the use of highly damaging capabilities against the Russian homeland that could threaten the state or the regime, and terminate hostilities on terms acceptable to Moscow.

Since the 1980s, Soviet military strategists and senior leaders have sought to address the challenge posed by the precision revolution. They have been grappling with the threat of massed aerospace attack, in which the United States would employ long-range precision-guided weapons, electronic warfare, with tactical and long-range aviation, elements of which could be conducted directly from the United States. In the mid-2000s, the Russian military feared a disarming conventional strike (and some analysts still do), but the central fear is a sustained air campaign that paralyzes the Russian military and inflicts unacceptable damage on the country’s critical infrastructure. In recent years, the fear of a large aerospace attack has also been paired with concerns that it could be preceded by political warfare to destabilize the country. Degrading such an attack — mitigating its effects — is possible, but denying it is not. In Moscow’s reading, long-range precision-guided weapons are strategic capabilities because of the damage they can inflict on a country’s critical economic and military infrastructure. There is always a lingering fear of strategic surprise, and the belief that if escalation is likely, then Russia should take the lead rather than attempt a costly defense.

This is not just a question of conventional inferiority; the United States might not do any better against a massed cruise missile attack. The Russian goal has been to find deterrence answers to problems that do not have good warfighting solutions, to manage escalation, and to address the escalation dilemmas resulting from a force structure too inflexible to deter a strategic-level conventional attack or a regional conventional conflict against a militarily stronger adversary. Nuclear weapons remain an important intra-war deterrence tool to manage escalation and compensate for disadvantages in a conflict where aerospace power and precision-strike capabilities could prove decisive.

Key Assumptions

In Russian military thought, warfighting is discussed as distinct from deterrence. So important is this difference that in the Russian military the forces are functionally divided into categories of “general purpose” and “strategic deterrence.” The latter are further divided into offensive and defensive strategic forces. A simple example is the general-purpose role of a missile brigade, supporting an army in the field with precision strikes, versus its strategic deterrence role in firing long-range cruise missiles against critically important economic or military objects far beyond operational depths. Strategic offensive capabilities include long-range conventional weapons, nuclear weapons, directed-energy or cyber weapons, whereas defensive forces consist of missile defense, integrated air defense, and early warning radar systems.

Important assumptions guide Russian thinking in this realm. The first is that while general-purpose forces contribute to conventional deterrence and can win in a small armed conflict or local war, they are insufficient to deter a power like the United States together with a coalition of allies. Today, Russia’s military is much more capable than in the late 1990s or mid-2000s, but only strategic deterrence forces, armed with strategic conventional capabilities (offensive strike and aerospace defense), nonstrategic nuclear weapons, and strategic nuclear weapons, are effective deterrents in regional and large-scale wars. The deterrence stratagems in question are premised on raising the expected costs above that of anticipated gains. They include both preemptive and retaliatory use of force. In general, Russian military analysts assume that defense, while necessary, is cost-prohibitive in a regional or large-scale war. The notion that new anti-access and area-defense capabilities have led to newfound confidence in a deterrence-by-denial approach in Russian thinking is incorrect. More accurately, the Russian military seeks to deny the U.S. a quick or easy victory in the initial period of war, thereby changing the cost calculus relative to interests at stake.

Russian strategy, integrating nonnuclear and nuclear deterrence, is intended to solve a straightforward escalation dilemma stemming from a lack of force flexibility and capability in the 1990s: The United States could inflict unacceptable damage on Russia with conventional capabilities and attain victory with precision-guided weapons in the initial period of war while making minimal contact with Russian forces. Moscow’s answer would necessitate large-scale use of nonstrategic nuclear weapons in theater. This was an untenable situation, which led to the Russian military’s quest for both the ways and means to build a “deterrence ladder” with multiple rungs, and flexibility in conventional and nuclear options, to manage escalation. Conventional force modernization has not altered Russian thinking on the importance of nuclear weapons at higher thresholds of conflict, for intra-war deterrence, and ultimately for warfighting.

The Russian military sees an independent conventional war as possible, but believes conflict is unlikely to remain conventional as it escalates. This is not a departure from late-Soviet military thought. The military expects a great-power war between nuclear peers to eventually involve nuclear weapons, and is comfortable with this reality, unlike U.S. strategists. However, in contrast with Soviet thinking, the Russian military does not believe that limited nuclear use necessarily leads to uncontrolled escalation. The Russian military believes that calibrated use of conventional and nuclear capability is not only possible but may have decisive deterrent effects. This is not an enthusiastically embraced strategy, but an establishment’s answers to wicked problems, in the context of a great-power conflict, which have no easy or ideal solutions.

Strategic Deterrence

Russian approaches to contain, deter, and inflict different levels of damage on potential adversaries can be grouped under the umbrella term of “strategic deterrence” (strategicheskoe sderzhivanie), which has been evolving since the 2000s. In a 2017 speech in Sochi, Putin asserted that Russian defense policy is aimed at “providing guaranteed strategic deterrence, and, in the case of a potential external threat — its effective neutralization.” Strategic deterrence, in the sense used by the Russian president, is a holistic concept that envisions the integration of nonmilitary and military measures to shape adversary decision-making. Russia’s 2015 National Security Strategy defined strategic deterrence as a series of interrelated political, military, military-technical, diplomatic, economic, and informational measures to prevent the use of force against Russia, defend sovereignty, and preserve territorial integrity.

Russia uses strategic deterrence measures continuously — in peacetime not just to deter the use of force or threats against Russia, but to contain adversaries, and in wartime to manage escalation. Nonmilitary measures (considered nonforceful) include “political, diplomatic, legal, economic, ideological, and technical-scientific.” However, deterrence in Russian thinking is founded first and foremost on the coercive power of military measures (forceful in character). Military measures consist of demonstrations of military presence and military power, raising readiness to wartime levels, deploying forces, demonstrating readiness within the forces and means designated to deliver strikes (including with nuclear weapons), and conducting or threatening to conduct single or grouped strikes (which again include nuclear weapons). Such measures are employed in peacetime to deter direct aggression or the use of military pressure against Russian interests. In wartime they are designed to manage escalation and to de-escalate or cease hostilities on terms acceptable to Russia.

Escalation Management and War Termination

Russian stratagems can be divided up into phases of demonstrative actions operating under the principle of deterrence by fear-inducement (устрашение), and progressive infliction of damage, which is deterrence through limited use of force (силовое сдерживание). Deterrence by fear-inducement operates through demonstrative acts, which, during peacetime or a period of perceived military threat, communicate that Russian forces have the means and resolve to inflict damage against an opponent’s vitally important targets. These objects — for example, nuclear and hydroelectric power plants, chemical and petroleum industry facilities, and others — are those that might lead to significant economic losses or loss of life, or impact the target nation’s way of life.

Conversely, deterrence through limited use of force is based on destroying or disabling critically important objects relevant to the economy or the military, but choosing those targets that would not lead to loss of civilian life or risk unintended escalation. The strategy involves signaling the ability and willingness to use force, prior to actual escalation. Either as a preemptive measure, when there is an imminent threat of attack, or at the outset of the conflict, Russian military analysts envision inflicting progressive levels of damage beginning with single and grouped strikes using conventional weapons, and issuing nuclear threats. This constitutes a demonstrative use of force, and could subsequently include nuclear use for demonstration purposes. Both deterrence by fear-inducement and deterrence through limited use of force are iterative processes, not singular attempts to manage escalation via a specific operational ploy. Hence much depends on the opponent’s reaction. Furthermore, applying force does not necessitate use of precision-guided weapons, but can include offensive cyber operations and directed energy weapons, or what the Russian armed forces term “weapons based on new physical principles.”

If escalation cannot be managed, then capabilities are employed en masse for warfighting and retaliation. Generally, the Russian military sees escalation management as possible up to larger-scale employment of nuclear weapons. Subsequent use of force falls primarily into the retaliation category.

As a regional or large-scale conflict escalates, the Russian military could follow the employment of nonnuclear capabilities with single and grouped nuclear strikes using nonstrategic nuclear weapons, either for the purposes of demonstration; against a target in a third country; or against deployed adversary forces. As prospects for managing escalation decline, use of force intensifies with extensive use of precision-guided conventional weapons in a regional war. In a large-scale war, the Russian military expects that its forces will use nonstrategic nuclear weapons in warfighting, together with limited use of strategic nuclear weapons.

The purpose of limited strikes is to shock or otherwise stun opponents, making them realize the economic, political, and military costs they will pay for further aggression, but also to offer them off-ramps. The approaches described above are not mechanistic. Military science may give the impression that these actions are preprogrammed, but much depends on the context and what Russian political leadership authorizes (and the manner in which that authority is given). The figure below offers one representation of the potential courses of action.

(Source: Michael Kofman, Anya Fink, Jeffrey Edmonds, “Russian Strategy for Escalation Management: Evolution of Key Concepts,” CNA paper, April 2020. Data from A.V. Skrypnik, “On a possible approach to determining the role and place of directed energy weapons in the mechanism of strategic deterrence through the use of force,” Armaments and Economics, no. 3 (2012); A.V. Muntyanu and Yu.A. Pechatnov, “Challenging methodological issues on the development of strategic deterrence through the use of military force,” Strategic Stability, no. 3 (2010).)

Damage Levels

Russian military thinking on damage levels has evolved from calculations pegged to unacceptable damage — an absolute amount of destruction visited upon the adversary’s population and economic potential — to subjective or tailored forms of damage. Unacceptable damage is still the byword for Russian strategic nuclear forces. The exact percentage of damage to population and industry is unknown, but some writings base it on ensuring that 100 strategic nuclear warheads reach the U.S. homeland. However, the Russian military believes the actual level of damage required to manage escalation or deter adversaries is much lower, considering unacceptable damage excessive or overkill outside of strategic nuclear retaliation. The concept relevant for escalation management discourse is “deterrent damage,” which is a subjective level of damage that varies from country to country, and the operations envisioned apply this form of damage via “dosing.” For warfighting, the commonplace term is “assigned damage,” presumably set by the general staff in operational planning.

Deterrent damage has two basic components: the material damage inflicted, and the psychological effect based on the opponent’s reaction to the strike and its influence on other coalition members. The idea behind this approach is that damage will have cascading psychological effects on the target, and on the coalition of adversary states, depending on that country’s role. Russian military thinkers have yet to settle on a clear scope for deterrent damage and are struggling with how to quantify it, but it can be best framed as damage greater than the benefits the target expects to gain from using force, and an amount of pain ranging from reversible effects on one end of the spectrum all the way to “unacceptable damage” on the other.

Nuclear versus Nonnuclear Capabilities

In the 1990s, the Russian military debated the role of nonstrategic nuclear weapons in deterring regional war (a regional system of deterrence), and strategic nuclear forces as part of a global system of deterrence for large-scale war. These approaches remain today, but since then a system of nonnuclear deterrence has been established based on strategic conventional capabilities. Russian military strategists see conventional weapons as usable and coercive early on in a conflict or crisis, and naturally they carry far fewer escalatory risks. They have taken over deterrence tasks in the initial period of a regional war from nonstrategic nuclear weapons, and lesser conflicts like local wars.

However, Russia has no intention of replacing nuclear weapons with conventional capabilities across the board. No number of precision-guided weapons will lead the Russian military to forgo nonstrategic nuclear weapons and the threat of nuclear employment in an escalating conflict. The Russian military sees conventional and nuclear capabilities as complementary within its deterrence concepts, not as substitutions for one another.

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has largely disarmed of tactical nuclear weapons save the B-61 variants of gravity bombs, while Russia reduced its nonstrategic nuclear arsenal by about 75 percent. However, the Russian military has been modernizing and expanding nonstrategic nuclear weapons alongside strategic conventional ones. This suggests a different philosophy at work in terms of the balance between conventional and nuclear capabilities in Russian military strategy. Russia sees nuclear weapons as essential because their psychological impact, and deterrent effect, cannot be supplanted by conventional capabilities. They are an asymmetric investment to neutralize U.S. conventional advantages, representing a competitive strategy. Simply put, conventional weapons cannot match the deterrence bang for the ruble spent on nuclear weapons.

No less important is the theory that binds Russian conventional, nonstrategic, and strategic nuclear weapons. Limited use of conventional weapons has added coercive effect if nuclear use is expected to follow, and it lends credibility to follow-on nuclear threats, which by themselves might prove unconvincing in early phases of escalation. A large strategic nuclear arsenal is not just important as a survivable nuclear deterrent. It raises the fear of uncontrolled nuclear escalation once nuclear weapons are used. This nuclear dread generates psychological pressure on the elites and population of a targeted state to avoid escalation once nuclear weapons are used.

Targeting

The Russian military thinking behind targeting, particularly with strategic conventional weapons for escalation management purposes, is to select objects or nodes whose destruction has the potential to create cascading effects on the system as a whole. Targets may, and likely will, include those that have both a deterrent effect and practical military value should the conflict continue; that is, there are targets that may be considered dual purpose. Some military thinkers propose targeting strategies dividing the approach between strikes aimed at the leadership, and those that seek to affect the population.

Although Russian military analysts propose different lists, they overlap considerably. Political, economic, and military-related targets often include nonnuclear power plants, administrative centers (political), civilian airports, roads and rail bridges, ports, key economic objects, important components of the defense-industrial complex, and sources of mass media and information. Military targets tend to include command and control centers; space-based assets; key communication nodes; systems for reconnaissance, targeting, navigation, and information processing; and locations where means of delivery for ballistic or cruise missiles are based. In general, Russian thinking on targeting seeks to avoid infrastructure whose destruction could result in unintended collateral damage, like dams or nuclear power plants, and lead to unintended counter-escalation from the opponent.

Strikes to inflict limited forms of damage, or large-scale use of the aforementioned capabilities, are executed via strategic operations, discussed in numerous writings, including Strategic Operation for the Destruction of Critically Important Targets and Strategic Nuclear Forces Operation. These joint operations allow the Russian general staff to leverage the force to achieve strategic effects on the adversary’s ability or will to fight.

The Question of Escalate to De-escalate

Whether Russia has a lowered nuclear threshold is a matter of perspective. Moscow sees nuclear weapons as essential for deterrence and useful for nuclear warfighting in regional or large-scale war. That is hardly a recent development, though it may be new to decision-makers in the United States. There is an erroneous perception in American policy circles that at some point Washington and Moscow were on the same page and shared a similar threshold for nuclear use in conflict. It is not clear that this imagined time period ever existed, but perhaps both countries viewed nuclear escalation as uncontrollable, or at least publicly described it as such during the late-Cold War period. In principle, Russian leadership does view nuclear use as defensive, forced by exigent circumstances, and in the context of regional or large-scale conflicts.

Compared to Russian military considerations of the late 1990s and early 2000s, the criteria for use of nuclear forces remains unchanged, and if anything the thinking has been refined over the last two decades, as has declaratory policy. The role of nonstrategic nuclear weapons has been pushed further into regional or large-scale war, with Russia preferring conventional options in a crisis and the initial period of conflict. What has changed in the last two decades is not so much the threshold, but more so the timing when nuclear weapons might come into play. There is strong doubt in Russian military circles that political leadership will authorize early, preemptive use of nuclear weapons. In general, despite some marginal voices who consistently call for early nuclear use, the consensus is that attempts to coerce with nuclear weapons early on will not be credible. This is precisely why the Russian military invested in complementary means of nonnuclear deterrence. However, Russia’s strategy of deterrence by fear-inducement when under military threat makes heavy use of nuclear signaling, which serves to create the impression that the country is far looser with its thinking on nuclear use than is actually the case.

Important differences exist between Russian military thinking on escalation management and what some have characterized as Russia’s early war-termination strategy, nicknamed “escalate to de-escalate,” where Moscow acts aggressively and seeks to terminate the war with preemptive nuclear use. De-escalation as envisioned by the Russian military means escalation management, which includes containing conflict to a specified threshold — for example, keeping a limited war from becoming a regional war — or deterring other states from becoming involved; containing the war geographically; attaining a cessation of hostilities on acceptable but not necessarily victorious terms; or simply generating an operational pause. It includes more than simply war termination. Successful escalation management results in escalation control, because escalation control is not something you do, but something you get as the result.

Single or grouped strikes may or may not result in follow-on nuclear escalation, but widespread use of nuclear weapons is not about escalation management. It is for general warfighting as a last-ditch effort in cases where the military is losing a war and the state is under threat. Can Russia find itself fighting a war that it perceives to be defensive in nature, and then resort to nuclear first use as the conflict escalates? Absolutely, but this proposition assumes a host of military and nonmilitary actions taken on both sides prior to nuclear escalation, rather than an attempt at preemptive nuclear coercion. There is no gimmicky “escalate to win” strategy, in which military strategists believe they can start and quickly end a conflict on their terms thanks to the wonders of nuclear weapons. The U.S. defense strategy community needs to put away this boogeyman and stop telling this scary tale like some kind of nuclear ghost story. The Russian military has a visibly different comfort level with nuclear weapons than the United States, and arguably always will, but it does not write of nuclear escalation in recklessly optimistic terms, incognizant of the associated risks.

Implications for American Strategy

One of the misperceptions about Russian nuclear strategy is that it takes advantage of lower-yield nuclear weapons that the United States does not have. This appears nowhere in Russian military writings or deliberations. There has never been a theory suggesting that asymmetry in yields presents a special escalation dilemma for the United States. The escalation dilemma would be that the United States would be forced to respond to a lower-yield weapon with a high-yield strategic weapon, thereby escalating the nuclear exchange. The “yield gap,” as Dr. Strangelove’s Gen. Buck Turgidson might have declared it had he written the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, is a matter of U.S. defense planners worrying about being self-deterred. It has little to do with Russian nuclear strategy, and it will have precious little effect on Russian thinking. Lower-yield weapons make Russia’s escalation management strategy more viable in practice, especially when considering that in a theater wide conflict they might be used in Eastern Europe or near Russia’s borders.

For the United States, attaining greater force flexibility and developing the ability to respond in kind with a limited number of low-yield nuclear weapons makes sense, but it also reduces Russia’s risk of uncontrolled nuclear escalation. This results in a schizophrenic nuclear posture: Declaratory policy proclaims that nuclear use is dangerous and uncontrollable, while American programmatic strategy contradicts those statements, suggesting that the United States plans to engage in limited nuclear counter-escalation and has bought the tools to do so. One of our findings is that Russian strategy has not been based on the premise that the United States is hamstrung by an asymmetry of yields. The U.S. escalation dilemma stems from its having much lower interests at stake, and its extending deterrence to distant allies, which cannot be resolved by strapping a low-yield warhead onto a submarine-launched ballistic missile.

Although our research explores national-level concepts, it focuses on military strategy and military thought, not political strategy or political intent. These military and national security concepts represent inputs into Russian political decision-making. Military strategy helps establish the potential courses of action, and offers insight into what political leadership might choose to do, but it cannot predict what political leadership will do, or how much confidence it will have in the military plans that are developed.

That said, Russia’s political leadership shows a strong interest and involvement in nuclear strategy, regularly attends military exercises that simulate nuclear use, and is conversant on the questions of nuclear policy. It would be wrong to dismiss Russian military thinking on this subject as general staff or military scientist machinations holding debates in the proverbial wilderness. Russian force structure, exercises, and signaling helps further substantiate the thinking found in Russian military writing. Furthermore, we are skeptical that there is a multiplicity of actors outside of the military, national security leadership, and defense research institutions involved in shaping Russian nuclear strategy.

The challenge posed by Russian nuclear strategy is not just a capability gap, but a cognitive gap. The Russian military establishment has spent decades thinking and arguing about escalation management, the role of conventional and nuclear weapons, targeting, damage, etc. In the United States, precious little attention has been paid to the question of escalation management, which is overshadowed by planning for warfighting. Thinking on escalation management and limited nuclear war should take priority, because the political leadership of any state entering a crisis with a nuclear peer will inevitably wish to be assured that a plausible strategy for escalation management and war termination exists. Otherwise, leaders may back down because the risks may simply outweigh U.S. interests at stake, and the defense establishment’s ideas for managing that potential escalation prove unconvincing.

Simply adding flexibility to the force structure — buying missiles or warheads — will not make for a credible strategy, nor will boisterous policy language deter U.S. adversaries. Seeking to dissuade Russian planners by telling them their strategy won’t work will only reinforce their belief that the United States is deeply concerned about Russian limited nuclear employment, and validate the thinking behind it. There is a general sense in U.S. military circles that it is dangerous for Russia to believe that nuclear escalation can be controlled. Yet by imagining that the United States can have conventional-only wars with nuclear powers, where the stakes for them are likely to become existential, there is an implicit assumption in U.S. defense strategy that Washington can somehow control escalation and dissuade nuclear use on the part of others, without any discernible plan for accomplishing this feat.

Any conflict with Russia will always be implicitly nuclear in nature. If it is not managed, then the logic of such a war is to escalate to nuclear use. The United States needs to develop its own strategy for escalation management, and a stronger comfort level with the realities of nuclear war.

Become a Member

Michael Kofman serves as director and senior research scientist at CNA Corporation and a fellow at the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute. Previously he served as program manager at the National Defense University and a nonresident fellow at Modern War Institute at West Point. The views expressed here are his own.

Anya Loukianova Fink is a research analyst at CNA and a research associate at the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland. Previously, she was a fellow in the U.S. Senate and at the RAND Corporation. She holds a PhD in international security and economic policy from the University of Maryland, College Park. The views expressed here are her own.

Image: ru:Участник:Goodvint

Commentary

No comments:

Post a Comment