Democrats going nuclear to rein in Trump's arms buildup

Democrats going nuclear to rein in Trump's arms buildup

Control of the House will give them 'the power of no — the ability to block programs, cut funding, withhold agreement.'

By

BRYAN BENDER 11/24/2018 07:15 AM EST

Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) who is set to become the first progressive in decades to run the House Armed Services Committee. | Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Democrats preparing to take over the House are aiming to roll back what they see as

President Donald Trump's overly aggressive nuclear strategy.

Their goals include eliminating money for Trump’s planned expansion of the U.S. atomic arsenal, including a new long-range ballistic missile and development of a smaller, battlefield nuclear bomb that critics say is more likely to be used in combat than a traditional nuke.

They also want to stymie the administration's efforts to unravel arms control pacts with Russia. And they even aim to dilute Trump's sole authority to order the use of nuclear arms, following the president’s threats to unleash “fire and fury” on North Korea and other loose talk about doomsday weapons.

The incoming House majority will have lots of leverage, even with control of only one chamber in the Capitol, veterans of nuclear policy say. They point to precedents in which a Democratic-controlled House cut funding for Ronald Reagan’s MX nuclear missile and a Democratic-led Congress canceled the development of a new atomic warhead under George W. Bush.

"

They can block funding for weapon systems," said Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association in Washington. "The Democrats’ ascendancy will prove a much-needed check on the Trump administration's nuclear weapons policy and approaches."

Leading the charge is Rep. Adam Smith of Washington state, who is set to become the first progressive in decades to run the House Armed Services Committee, which is responsible for setting defense policy through the annual National Defense Authorization Act.

Smith has long criticized both

President Barack Obama and Trump’s $1.2 trillion, 30-year plan to upgrade all three legs of the nuclear triad — land-based missiles, submarines and bombers — as both unaffordable and dangerous overkill.

He's made it clear in recent days that revamping the nation's nuclear strategy will be one of his top priorities come January, when he is widely expected to take the gavel of the largest committee in Congress.

"The rationale for the triad I don't think exists anymore. The rationale for the numbers of nuclear weapons doesn't exist anymore," Smith told the Ploughshares Fund, a disarmament group, at a recent gathering of the Democratic Party's nuclear policy establishment.

The daylong conference included leading lawmakers, former National Security Council aides, peace activists and an ex-secretary of Defense, William Perry, who was once an architect of many of the nation's nuclear weapons but is now a leading proponent for a major downsizing.

Arms control and disarmament groups see Smith's emergence as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to craft a much more sensible approach to nuclear weapons and reduce the danger of a global conflict.

The mere appearance of a would-be Armed Services chairman at the recent gathering demonstrated how much circumstances have changed.

"I have never seen a chairman give nuclear policy such a high priority, have such personal expertise in the area, and be so committed to dramatic change," said Joe Cirincione, president of Ploughshares Fund.

Cirincione served as a staffer to then-Rep. Les Aspin (D-Wis.), who chaired the panel during the fierce debates over nuclear weapons policies in the 1980s, which he sees as an instructive period for today.

"I know that a Democratic House can have a major impact on nuclear policy," he said. "It is the power of no — the ability to block programs, cut funding, withhold agreement to dangerous new policies. Democrats may not be able to enact new policies, but they can force compromises."

High on the priority list is halting or delaying the development of a planned new nuclear bomb that would have less explosive power than a more traditional atomic bomb. The Trump administration's Nuclear Posture Review called for the so-called low-yield weapon last year.

Advocates assert that the weapon, to be launched from a submarine, will provide military commanders with more options and better deter nations such as Russia, China, North Korea and Iran that are building up their own nuclear arsenals. Such a modest nuke would not destroy a city but would devastate a foreign army — and adversaries would have reason to fear that the U.S. might use it in a first strike.

But Smith, who will also influence the House Appropriations Committee's recommendations for Pentagon funding, insists such a new weapon "brings us no advantage and it is

dangerously escalating."

"It just begins a new nuclear arms race with people just building nuclear weapons all across the board in a way that I think places us at greater danger," he told Ploughshares Fund.

Democrats are expected to revive legislation proposed earlier this fall in both the House and Senate to try to roll back the program.

“

There’s no such thing as a low-yield nuclear war," said Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), one of the co-sponsors, who also gave his pitch at the Ploughshares Fund gathering this month. "Use of any nuclear weapon, regardless of its killing power, could be catastrophically destabilizing."

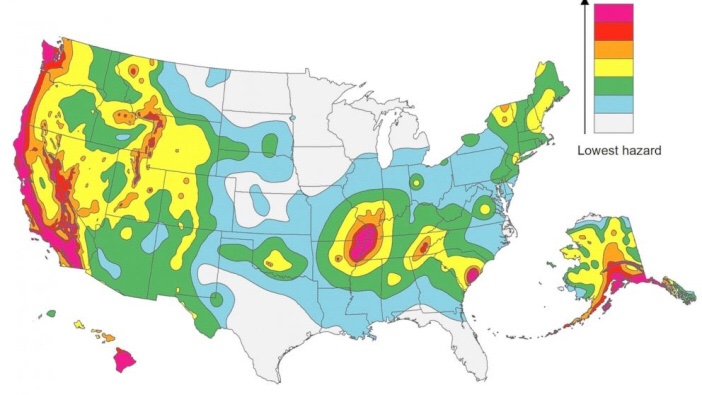

Leading Democrats also have their sights on a new intercontinental ballistic missile that is under development as the future land-based leg of the nuclear triad. The Ground Based Strategic Deterrent is set to replace current ICBMs that are deployed in underground silos in Western states such as Montana, Wyoming and North Dakota.

"The ICBM is where the debate will focus," predicted Mieke Eoyang, vice president of national security at Third Way, a centrist think tank, and a former aide on the House Intelligence Committee.

One key argument will be cost, she added.

"People make the case for all three legs of the triad, but when you look at the budget situation, the Pentagon is going to have to make some tough choices," Eoyang said in an interview. "The modernization of the triad is a big-ticket item that comes over and above what current Defense Department needs are — at a time when budget pressures are coming the other way."

Critics also argue that the ICBM has outlived its usefulness.

Perry, who served as Pentagon chief for President Bill Clinton, has argued that the land-based ICBM is the leg of the triad that is most prone to miscalculation and an accidental nuclear war. He said submarine- and aircraft-launched nuclear weapons would provide a sufficient deterrent on their own.

But not everyone thinks cutting one leg of the triad will be easy. They cite the political clout of defense contractors and their political supporters in both parties, including the so-called ICBM Caucus — especially in the Senate, which will remain under Republican control.

"They won't be able to take on the triad," warned former Rep. John Tierney (D-Mass.), executive director of the Center for Arms Control and Nonproliferation, who chaired the national security and foreign affairs panel of the Government Oversight and Reform Committee.

But Tierney and others said the House can pursue other areas for reshaping nuclear policy — and force the Senate to take up their proposals.

One way is to revive legislation adopting a "no first use" policy for nuclear weapons, declaring that a president could not order the use of nuclear weapons without a declaration of war from Congress.

"We want to avoid the miscalculation of stumbling into a nuclear war," Smith said. "And this is where I think the No First Use Bill is incredibly important: to send that message that we do not view nuclear weapons as a tool in warfare."

The unfolding strategy will also rely on inserting new reporting requirements in defense legislation as a delaying tactic on some nuclear efforts or to compel the administration to reconsider its opposition to some arms control treaties.

While the president negotiates treaties and the Senate is vested with the constitutional authority to ratify them, the House also has some power to force the administration's hand.

Trump, citing Russian violations, has threatened to pull out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty that Reagan signed with the then-Soviet Union in 1987. He recently sent national security adviser John Bolton to Moscow to relay the message.

But critics say the landmark treaty, which banned land-based missiles with ranges from 50 to 5,500 kilometers, is still worth trying to salvage with the Russians. And Democrats can try to force the Trump administration to curtail plans for a new cruise missile that would match the Russians.

The Democrats can put the cruise missile "back on its heels," Tierney said. "Sometimes they can delay, sometimes defeat."

Democrats also worry that the Trump administration will opt to not renew the New START Treaty with Russia, which expires in early 2021. That pact, reached in 2010, mandates that each side can have no more than 1,550 deployed nuclear weapons and requires regular inspections to ensure each side is complying.

Trump and his advisers "are opposed to multilateralism just based on principle," Smith told the crowd of arms control advocates. "That is John Bolton’s approach, that he doesn’t want to negotiate with the rest of the world, almost regardless of what it is that we negotiate."

But Kimball, who met recently with Smith, said Democrats have options on that front, too.

"If the Trump administration threatens to allow New START to expire in 2021, the Democrats are not under any obligation to fund the administration's request for nuclear weapons," Kimball said.

He pointed out that Obama secured bipartisan Senate support for ratifying the New START treaty in return for a pledge to increase spending on upgrading the nuclear arsenal and new missile defense systems. "That linkage works the other way, too," Kimball said.

What is clear is that the nuclear arms control crowd sees Smith as the best hope for change in many years.

"I don't think it is going to be easy, but we see a chance that we haven't seen in a long time to have a different path forward on nuclear weapons," said Stephen Miles, director of Win Without War, an antiwar group. "There isn't enough money available for the wild plans we had before, let alone Trump's new objectives."

ANALYSIS: Muqtada al-Sadr and rising tensions between Iran and Iraq

ANALYSIS: Muqtada al-Sadr and rising tensions between Iran and Iraq After his surprise victory, the people were hopeful that his pre-election rhetoric would indicate what al-Sadr would actually do now that he was in legitimate power. (AFP)

After his surprise victory, the people were hopeful that his pre-election rhetoric would indicate what al-Sadr would actually do now that he was in legitimate power. (AFP) Moqtada al-Sadr (L) during a news conference with Iraqi prime Minister Haider al-Abadi in Baghdad on May 20, 2018. (Iraqi Prime Minister Media Office/Handout via Reuters)

Moqtada al-Sadr (L) during a news conference with Iraqi prime Minister Haider al-Abadi in Baghdad on May 20, 2018. (Iraqi Prime Minister Media Office/Handout via Reuters)

Iran Nuclear Chief to EU: 'Ominous' Consequences If Deal Breaks Down

Iran Nuclear Chief to EU: 'Ominous' Consequences If Deal Breaks Down

The Only

The Only