Bracken: The reality of the nuclear threat

Iran on the brink of a nuclear weapon — but now talking. North Korea,

nuclear-armed, and reading too much like a Shakespeare history play,

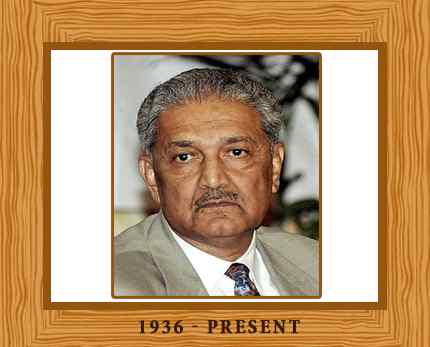

full of intrigue, deaths, and plots. Pakistan, officially an ally, ranks

high on any list of potential leak-points for nuclear knowledge,

weapons, and danger.

As 2014 begins, what does the world look like to national security expert Paul Bracken?

“I think on nuclear issues, we’re probably safe for the next two or three years, safe from a nuclear war,” he said.

An academic expert on security issues, international relations,

military capabilities and strategy, the longtime Ridgefielder is a Yale

professor, a member of the Council of Foreign Relations and the author

of many books, most recently

The Second Nuclear Age: Strategy, Danger and the New Power Politic, which came out a year ago.

“It is a scary book,” he admitted. “I got that comment from people who are old pros at this, who shouldn’t be scared.”

The book is an extended argument — a plea, almost — for the United

States to outgrow the Cold War era blinders that still guide debate and

think more, and more seriously, about the realities of a world with 10

nuclear powers.

Asked what he sees ahead, Dr. Bracken spoke first of some reassuring things, then got to the scary stuff.

Even with all the craziness going on internationally, and the

emergence of smaller nuclear-armed states in the Middle East and Asia,

there are some positives.

“These countries don’t have weapons that can reach the US — this is the good news list,” he said.

“These arsenals are horrible, but small, compared to the Cold War,”

he said. “If 1% of those Cold War arsenals had ever been fired, the

world would have ended.

“Another piece of good news is we may luck out on one of these

countries — like North Korea may collapse without firing a shot,” he

said. “There may be changes in Pakistan.”

But Dr. Bracken has a sizable bad news list, as well.

“You have these regional powers — North Korea, Pakistan, Israel, I

think Iran — who correctly feel that their national existence is

threatened. And I don’t see us lucking out in each and every one of

these cases,” he said.

“Item number two is that it’s easy to get a nuclear weapon if you choose to do so — easier than it was before.

“From the 1960s until the late 1990s, any kind of arms control was

likely to work, because these countries didn’t have the technological

capacity, the engineering capacity, to go down the nuclear road,” he

said.

In

The Second Nuclear Age Dr. Bracken often compares today’s challenges to problems after World War II.

“Winging it, as we did in the late ‘40s, could be more dangerous this

time,” he said. “There are so many more states which could interact is

one reason. The other reasons is, these cultures are so different from

the US-Soviet competition. There, you had two very conservative,

risk-averse countries — we now know. But we don’t understand the

Pakistani calculus of risk, or that of Iran.

“I find in Washington there’s an expectation that the world is going

to return to stable deterrence, between India and Pakistan, North and

South Korea, Israel and Iran. And this means using the Cold War history,

looking back in a rear-view mirror and projecting it into the future …

But with these very different cultures you could get very different

behaviors, much more dangerous behaviors.

“There’s a ‘curse of knowledge’ academics talk about. We now know how

the Cold War ended. And the second half of the Cold War there were no

major nuclear threats, so people apply that. In doing that, people

forget even the paranoia of the Cold War — red scares, civil defense

drills, crazy generals.”

US policy seeks to halt the spread of nuclear weapons.

“But that’s not going to happen, the prevention of the spread of

nuclear weapons,” Dr. Bracken said. “You’ve got nine nuclear weapons

states now, so you’ve got to try to figure out how to live in this

world.”

And, things are getting more complex.

“A revolution in technology is taking place on top of the spread of

nuclear weapons,” Dr. Bracken said “It’s like the 1950s, when jet

aircraft, radar, missiles, and satellites were all developed the same

time as the development of the atomic bomb. Today, cyberwar, drones, and

precision guidance of missiles are developing alongside the spread of

the atomic bomb.

“The interesting question, to me, is how this technology cycle aligns with the trends in international politics…

“Pakistan is about to produce small, backpack atomic bombs. These

could easily fall into the hands of a terrorist group if the government

of Pakistan collapses,” he said.

In the early Cold War, when the fear was a nuclear-armed Soviet Union, serious long-term thinking was rare.

“They’d make it up as they go along, and that’s what’s happening

now,” Dr. Bracken said. “What I try to do in the book is look at the

lessons and what happened back then, to see which of those lessons do

and do not apply.”

One lesson is that serious action on a problem usually comes after

there’s a crisis. “It’s just like building the sea walls after Hurricane

Katrina,” he said.

Policy making needs cold-eyed realism, but Dr. Bracken says “fictions” may be useful.

“In the Cold War it was a very useful fiction to pretend that there

were only two nuclear countries. And that begs the question: What are

useful fictions that we should be building today?”

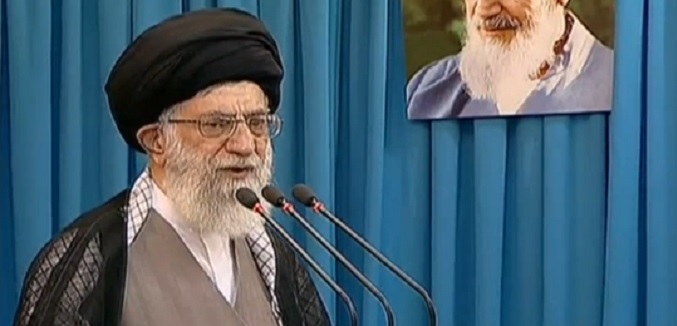

There’ve been remarkable developments, but in the year since the book

came out little has happened that changes Dr. Bracken’s view of the

world.

“The trends carried on pretty much as I described them,” he said. “I

argue in the book that US policy was morphing from preventing Iran from

getting nuclear weapons to containment. And the recent interim agreement

with Iran acknowledges that Iran has a right to enrich, and accepts the

existence of a large Iranian nuclear infrastructure.”

As for the talks, “I’d put the chance of them leading to an agreement

to end the Iranian nuclear program at zero. I’d put the chances of them

leading to an agreement to end the Iranian nuclear weapons program at

10%. But I am nonetheless in favor of the talks,” he said.

It’s not about strengthening Iranian moderates, either.

“Looking at this problem as reinforcing the doves at the expense of

the hawks inside Iran fails to conceptualize career opportunism and

personal ambition inside Iran, which is much greater than their internal

argument over strategy.

“It’s hard to find a single historical case in the last 100 years where playing to the doves worked,” he said.

American ally Israel is unhappy with the talks, but Dr. Bracken

believes “the chances of Israel attacking Iran are essentially zero.

Israel doesn’t have the military capability, without the US. I think

Iran’s going to get a nuclear weapon. It’s just going to be two or three

years down the road. So, these talks kick the can down the road — which

is better than starting a large, bloody, unsuccessful war.”

The Cold War has lessons.

“You had some very smart people from extreme ends of the political

spectrum, right and left, advocate preventative war against the Soviet

Union,” he said.

He’s skeptical of using war as way of handling problems.

“I have this idea that before you attack another country there ought

to be a law that you think about what’s going to happen for one hour,”

Dr. Bracken said.

The criticism is bi-partisan. he insists: “We didn’t do this in the case of Iraq or, more recently, the Afghan surge.”

What about Afghanistan?

“We should just get out,” he said. “Let me add, that’s exactly what we’re doing.

“If we stayed there with 15,000 troops — let’s go to 115,000 — it

won’t affect the outcome of what’s going to happen in Afghanistan.”

Pakistan, next door, is also problematic. It’s an Islamic state, of

questionable stability, with nuclear weapons — but without real control

of them.

“I think I know as much about this as anybody in the world,” he said.

“They don’t have control of their nukes, when it matters. They do have

control when it doesn’t matter. That is, in peacetime, when there’s no

threat to anything, the weapons are under heavy lock and guard. But if

you move the weapons, as you will in a crisis, you have to take some of

the locks off.”

Dr. Bracken thinks the US and its major rivals can get along — not to say they will.

“We don’t have to be enemies, at least on several issues. And there’s

many examples where that’s the case. And it’s also a lesson of the Cold

War, where we did reach several agreements that capped the arms race

with Russia. And we’re seeing that emerge again with Russia’s assistance

in the Syria chemical problem.”

With China, too, competition and cooperation mix.

“In the April 2013 North Korean crisis, the US canceled some routine

ICBM test launches,” Dr. Bracken said. “We thought having the test at

the height of the crisis with North Korea would look like we were trying

to intimidate China. And we wanted China to work with us on North

Korea, so we didn’t want to threaten them. Exactly this sort of thing

occurred in the cold war.”

A preference for keeping crises in control is generally shared by the leaders of major powers, even regional powers.

But there are other players, aspiring leaders, groups like Al Qaeda

that may feel see less to lose and more to gain by unleashing nuclear

chaos.

“We think that most countries would be scared of selling or giving a

bomb to sub-national groups,” Dr. Bracken said. “We could be wrong about

that.”