The most recent one near New York City occurred in August of 1884. Centered off Long Island’s Rockaway Beach, it was felt over 70,000 square miles. It also opened enormous crevices near the Brooklyn reservoir and knocked down chimneys and cracked walls in Pennsylvania and Connecticut. Police on the Brooklyn Bridge said it swayed “as if struck by a hurricane” and worried the bridge’s towers would collapse. Meanwhile, residents throughout New York and New Jersey reported sounds that varied from explosions to loud rumblings, sometimes to comic effect. At the funeral of Lewis Ingler, a small group of mourners were watching as the priest began to pray. The quake cracked an enormous mirror behind the casket and knocked off a display of flowers that had been resting on top of it. When it began to shake the casket’s silver handles, the mourners decided the unholy return of Lewis Ingler was more than they could take and began flinging themselves out windows and doors.

Not all stories were so light. Two people died during the quake, both allegedly of fright. Out at sea, the captain of the brig Alice felt a heavy lurch that threw him and his crew, followed by a shaking that lasted nearly a minute. He was certain he had hit a wreck and was taking on water.

A day after the quake, the editors of The New York Times sought to allay readers’ fear. The quake, they said, was an unexpected fluke never to be repeated and not worth anyone’s attention: “History and the researches of scientific men indicate that great seismic disturbances occur only within geographical limits that are now well defined,” they wrote in an editorial. “The northeastern portion of the United States . . . is not within those limits.” The editors then went on to scoff at the histrionics displayed by New York residents when confronted by the quake: “They do not stop to reason or to recall the fact that earthquakes here are harmless phenomena. They only know that the solid earth, to whose immovability they have always turned with confidence when everything else seemed transitory, uncertain, and deceptive, is trembling and in motion, and the tremor ceases long before their disturbed minds become tranquil.”

That’s the kind of thing that drives Columbia’s Heather Savage nuts.

Across town, Charles Merguerian has been studying these faults the old‐fashioned way: by getting down and dirty underground. He’s spent the past forty years sloshing through some of the city’s muckiest places: basements and foundations, sewers and tunnels, sometimes as deep as 750 feet belowground. His tools down there consist primarily of a pair of muck boots, a bright blue hard hat, and a pickax. In public presentations, he claims he is also ably abetted by an assistant hamster named Hammie, who maintains his own website, which includes, among other things, photos of the rodent taking down Godzilla.

That’s just one example why, if you were going to cast a sitcom starring two geophysicists, you’d want Savage and Merguerian to play the leading roles. Merguerian is as eccentric and flamboyant as Savage is earnest and understated. In his press materials, the former promises to arrive at lectures “fully clothed.” Photos of his “lab” depict a dingy porta‐john in an abandoned subway tunnel. He actively maintains an archive of vintage Chinese fireworks labels at least as extensive as his list of publications, and his professional website includes a discography of blues tunes particularly suitable for earthquakes. He calls female science writers “sweetheart” and somehow manages to do so in a way that kind of makes them like it (although they remain nevertheless somewhat embarrassed to admit it).

It’s Merguerian’s boots‐on‐the‐ground approach that has provided much of the information we need to understand just what’s going on underneath Gotham. By his count, Merguerian has walked the entire island of Manhattan: every street, every alley. He’s been in most of the tunnels there, too. His favorite one by far is the newest water tunnel in western Queens. Over the course of 150 days, Merguerian mapped all five miles of it. And that mapping has done much to inform what we know about seismicity in New York.

Most importantly, he says, it provided the first definitive proof of just how many faults really lie below the surface there. And as the city continues to excavate its subterranean limits, Merguerian is committed to following closely behind. It’s a messy business.

Down below the city, Merguerian encounters muck of every flavor and variety. He power‐washes what he can and relies upon a diver’s halogen flashlight and a digital camera with a very, very good flash to make up the difference. And through this process, Merguerian has found thousands of faults, some of which were big enough to alter the course of the Bronx River after the last ice age.

His is a tricky kind of detective work. The center of a fault is primarily pulverized rock. For these New York faults, that gouge was the very first thing to be swept away by passing glaciers. To do his work, then, he’s primarily looking for what geologists call “offsets”—places where the types of rock don’t line up with one another. That kind of irregularity shows signs of movement over time—clear evidence of a fault.

Merguerian has found a lot of them underneath New York City.

These faults, he says, do a lot to explain the geological history of Manhattan and the surrounding area. They were created millions of years ago, when what is now the East Coast was the site of a violent subduction zone not unlike those present now in the Pacific’s Ring of Fire.

Each time that occurred, the land currently known as the Mid‐Atlantic underwent an accordion effect as it was violently folded into itself again and again. The process created immense mountains that have eroded over time and been further scoured by glaciers. What remains is a hodgepodge of geological conditions ranging from solid bedrock to glacial till to brittle rock still bearing the cracks of the collision. And, says Merguerian, any one of them could cause an earthquake.

You don’t have to follow him belowground to find these fractures. Even with all the development in our most built‐up metropolis,

evidence of these faults can be found everywhere—from 42nd Street to Greenwich Village. But if you want the starkest example of all, hop the 1 train at Times Square and head uptown to Harlem. Not far from where the Columbia University bus collects people for the trip to the Lamont‐Doherty Earth Observatory, the subway tracks seem to pop out of the ground onto a trestle bridge before dropping back down to earth. That, however, is just an illusion. What actually happens there is that the ground drops out below the train at the site of one of New York’s largest faults. It’s known by geologists in the region as the

Manhattanville or 125th Street Fault, and it runs all the way across the top of Central Park and, eventually, underneath Long Island City. Geologists have known about the fault since 1939, when the city undertook a massive subway mapping project, but it wasn’t until recently that they confirmed its potential for a significant quake.

In our lifetimes, a series of small earthquakes have been recorded on the Manhattanville Fault including, most recently, one on October 27, 2001. Its epicenter was located around 55th and 8th—directly beneath the original Original Soupman restaurant, owned by restaurateur Ali Yeganeh, the inspiration for Seinfeld’s Soup Nazi. That fact delighted sitcom fans across the country, though few Manhattanites were in any mood to appreciate it.

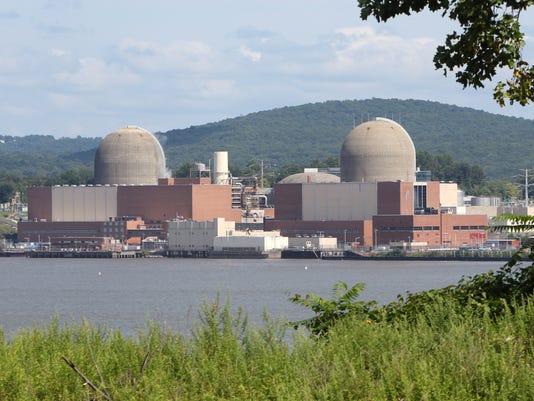

The October 2001 quake itself was small—about M 2.6—but the effect on residents there was significant. Just six weeks prior, the city had been rocked by the 9/11 terrorist attacks that brought down the World Trade Center towers. The team at Lamont‐Doherty has maintained a seismic network in the region since the ’70s. They registered the collapse of the first tower at M 2.1. Half an hour later, the second tower crumbled with even more force and registered M 2.3. In a city still shocked by that catastrophe, the early‐morning October quake—several times greater than the collapse of either tower—jolted millions of residents awake with both reminders of the tragedy and fear of yet another attack. 9‐1‐1 calls overwhelmed dispatchers and first responders with reports of shaking buildings and questions about safety in the city. For seismologists, though, that little quake was less about foreign threats to our soil and more about the possibility of larger tremors to come.

“Gee whiz!” He laughs when I pose this question. “That’s the holy grail of seismicity, isn’t it?”

He says all we can do to answer that question is “take the pulse of what’s gone on in recorded history.” To really have an answer, we’d need to have about ten times as much data as we do today. But from what he’s seen, the faults below New York are very much alive.

“These guys are loaded,” he tells me.

“We literally have no idea what’s happening in our backyard,” says Savage.

What we do know is that these quakes have the potential to do more damage than similar ones out West, mostly because they are occurring on far harder rock capable of propagating waves much farther. And because these quakes occur in places with higher population densities, these eastern events can affect a lot more people. Take the 2011 Virginia quake: Although it was only a moderate one, more Americans felt it than any other one in our nation’s history.

That’s the thing about the East Coast: Its earthquake hazard may be lower than that of the West Coast, but the total effect of any given quake is much higher. Disaster specialists talk about this in terms of risk, and they make sense of it with an equation that multiplies the potential hazard of an event by the cost of damage and the number of people harmed. When you take all of those factors into account, the earthquake risk in New York is much greater than, say, that in Alaska or Hawaii or even a lot of the area around the San Andreas Fault.

Merguerian has been sounding the alarm about earthquake risk in the city since the ’90s. He admits he hasn’t gotten much of a response. He says that when he first proposed the idea of seismic risk in New York City, his fellow scientists “booed and threw vegetables” at him. He volunteered his services to the city’s Office of Emergency Management but says his original offer also fell on deaf ears.

“So I backed away gently and went back to academia.”

Today, he says, the city isn’t much more responsive, but he’s getting a much better response from his peers.

He’s glad for that, he says, but it’s not enough. If anything, the events of 9/11, along with the devastation caused in 2012 by Superstorm Sandy, should tell us just how bad it could be there.

He and Savage agree that what makes the risk most troubling is just how little we know about it. When it comes right down to it, intraplate faults are the least understood. Some scientists think they might be caused by mantle flow deep below the earth’s crust. Others think they might be related to gravitational energy. Still others think quakes occurring there might be caused by the force of the Atlantic ridge as it pushes outward. Then again, it could be because the land is springing back after being compressed thousands of years ago by glaciers (a phenomenon geologists refer to as seismic rebound).

“We just have no consciousness towards earthquakes in the eastern United States,” says Merguerian. “And that’s a big mistake.”

Adapted from Quakeland: On the Road to America’s Next Devastating Earthquake by Kathryn Miles, published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Kathryn Miles. Thanks

NEW

YORK IS 40 YEARS OVERDUE A MAJOR EARTHQUAKE AND AMERICA ISN'T PROPERLY

PREPARED, 'QUAKELAND' AUTHOR KATHRYN MILES TELLS TREVOR NOAH

NEW

YORK IS 40 YEARS OVERDUE A MAJOR EARTHQUAKE AND AMERICA ISN'T PROPERLY

PREPARED, 'QUAKELAND' AUTHOR KATHRYN MILES TELLS TREVOR NOAH