Don’t forget about earthquakes, feds tell city

Although

New York’s modern skyscrapers are less likely to be damaged in an

earthquake than shorter structures, a new study suggests the East Coast

is more vulnerable than previously thought. The new findings will help

alter building codes.

By Mark Fahey

July 18, 2014 10:03 a.m.

The

2014 maps were created with input from hundreds of experts from across

the country and are based on much stronger data than the 2008 maps, said

Mark Petersen, chief of the USGS National Seismic Hazard Mapping

Project. The bottom line for the nation’s largest city is that the area

is at a slightly lower risk for the types of slow-shaking earthquakes

that are especially damaging to tall spires of which New York has more

than most places, but the city is still at high risk due to its

population density and aging structures, said Mr. Petersen.

“Many

of the overall patterns are the same in this map as in previous maps,”

said Mr. Petersen. “There are large uncertainties in seismic hazards in

the eastern United States. [New York City] has a lot of exposure and

some vulnerability, but people forget about earthquakes because you

don’t see damage from ground shaking happening very often.”

Just because they’re infrequent doesn’t mean that large and potentially disastrous earthquakes can’t occur in the area. The new maps put the largest expected magnitude at 8, significantly higher than the 2008 peak of 7.7 on a logarithmic scale.The

scientific understanding of East Coast earthquakes has expanded in

recent years thanks to a magnitude 5.8 earthquake in Virginia in 2011

that was felt by tens of millions of people across the eastern U.S. New

data compiled by the nuclear power industry has also helped experts

understand quakes.

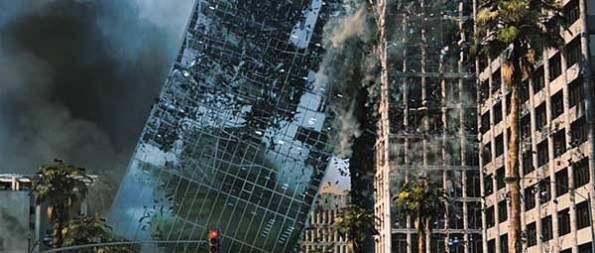

Oddly

enough, it’s not the modern tall towers that are most at risk. Those

buildings become like inverted pendulums in the high frequency shakes

that are more common on the East Coast than in the West. But the city’s

old eight- and 10-story masonry structures could suffer in a large

quake, said Mr. Lerner-Lam. Engineers use maps like those released on

Thursday to evaluate the minimum structural requirements at building

sites, he said. The risk of an earthquake has to be determined over the

building’s life span, not year-to-year.

“If

a structure is going to exist for 100 years, frankly, it’s more than

likely it’s going to see an earthquake over that time,” said Mr.

Lerner-Lam. “You have to design for that event.”

The

new USGS maps will feed into the city’s building-code review process,

said a spokesman for the New York City Department of Buildings. Design

provisions based on the maps are incorporated into a standard by the

American Society of Civil Engineers, which is then adopted by the

International Building Code and local jurisdictions like New York City.

New York’s current provisions are based on the 2010 standards, but a new

edition based on the just-released 2014 maps is due around 2016, he

said.

“The

standards for seismic safety in building codes are directly based upon

USGS assessments of potential ground shaking from earthquakes, and have

been for years,” said Jim Harris, a member and former chair of the

Provisions Update Committee of the Building Seismic Safety Council, in a

statement.

The

seismic hazard model also feeds into risk assessment and insurance

policies, according to Nilesh Shome, senior director of Risk Management

Solutions, the largest insurance modeler in the industry. The new maps

will help the insurance industry as a whole price earthquake insurance

and manage catastrophic risk, said Mr. Shome. The industry collects more

than $2.5 billion in premiums for earthquake insurance each year and

underwrites more than $10 trillion in building risk, he said.

“People

forget about history, that earthquakes have occurred in these regions

in the past, and that they will occur in the future,” said Mr. Petersen.

“They don’t occur very often, but the consequences and the costs can be

high.”

No comments:

Post a Comment